Click here to listen. Transcript below.

The stories about Red Hill read like hyperbole, like Paul Bunyon or Mike Fink stories. Commended by the Canadian government for a life-saving rescue at the age of nine, rescuing a tourist from a collapsing ice bridge, wounded in World War 1, several trips through the Niagara rapids in a barrel, bootlegging runs from Canada to the United States, the daring rescue of two men stuck on a grounded boat on the brink of the horseshoe falls, and an interstate chase after a stolen turtle. There were other rescues too, some human and some animal. He consulted most every Niagara River daredevil and would-be daredevil in the early part of the twentieth century including the great Harry Houdini.

Red Hill was inextricably linked to the Niagara River. For better or for worse, so was his family. His legacy lived on. After his death, there were more barrel runs, rescues, brushes with the law, and attempts at the falls.

Red Hill’s story is too big for one lifetime. The Hill family name carries with it decades of triumph, tragedy, valor, disgrace, life-saving heroics, death-defying feats, and deadly misfortune.

You can’t tell the story of Niagara Falls without the story of Red Hill.

Welcome to the Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. In this podcast, we’ll examine the bravery, stupidity, hubris, and eccentricity of people who have attempted daring feats at Niagara Falls. My name is Theodore Carter. I’m an author whose novel research went too far, and I got swept up in the current of stranger-than-fiction stories surrounding Niagara Falls. Now, I’m putting that research into this podcast.

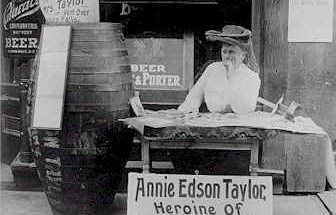

Twelve-year-old William “Red” Hill cut school to join the crowd downtown on Centre Street where the elderly school teacher Annie Edson Taylor stood next to her barrel and answered questions from a throng of reporters. In a few weeks, Taylor claimed she would travel down the falls in this vessel, and Hill, long fascinated with the powerful churn and swirl of the rapids examined the barrel’s strong staves and steel hoops.

Already, Hill had his own bonafides when it came to acts of bravery. He’d earned a medal from the Royal Canadian Humane Association several years earlier when he rescued his 4-year-old sister from a house fire. Taylor’s proposed act of courage mesmerized him, and he knew he’d be on hand to watch the stunt event if it meant skipping school, perhaps especially if it meant skipping school.

And he was there, pointing, staring, and waiting in anticipation to see what would happen as Taylor made her trip over the falls, clapping and cheering when she climbed out alive.

Annie Edson Taylor made going over Niagara Falls the pinnacle feat on the Niagara River, and this event would loom in the background of much of what happened to the Hill family for generations.

Growing up, Red Hill spent as much time as he could down at the river, floating branches down its powerful currents, trapping, hunting, and finding new routes on its bank. When he got older, sometimes, he earned extra money by plucking dead bodies out of the river, a necessary but dangerous task authorities were happy to farm out to rivermen like Hill.

Still, for years after Annie Edson Taylor’s feat, no one attempted to match her. Perhaps they could see, there wasn’t any money in it as was so clearly evidenced when one passed Mrs. Taylor on the street hawking souvenirs in a desperate attempt to maintain and monetize her celebrity. The potential benefit didn’t match the risks.

That changed when brash, big-talking professional stuntman Bobby Leach decided he would conquer the falls. An experienced daredevil, and braggart, Leach told anyone who would listen, including Red Hill, that he could match Taylor’s feat.

Hill didn’t much care for Leach’s bravado, perhaps in part because he harbored jealousy. For years, Leach had told reporters he intended to go over the falls, and in one article, Red Hill is quoted as saying that he might pull off the stunt himself if Leach didn’t. At the same time, knowing every whirlpool and eddy of that river, knowing how the current shifted with the weather, gave Hill a respect for the River Leach didn’t have. Though Hill flirted with going over, he also repeatedly said whoever made such an attempt would be a fool.

Still, Leach did have an impressive daredevil resume. He’d leaped from a height of 154 feet into a pool of water in Madison Square Garden 1907. He’d parachuted from hot air balloons and in 1908 parachuted from Niagara Falls’s Steel Arch Bridge. He claimed to have twice shot the Niagara Gorge rapids in a barrel in 1898, though was disputed. He traveled through the falls again, with a crowd of witnesses this time in 1910. It was Red Hill who rescued Leach when his barrel became caught in an eddy, a dangerous fate that had killed daredevil Maude Willard.

In 1910, in the midst of Leach’s big talk, Captain Klaus Larson successfully navigated a boat through the whirlpool rapids, a feat celebrated widely, including by Larson himself, though his boat filled with water in Queenstown. Red Hill was there to save him.

Perhaps wanting to redirect the spotlight away from Larson, Leach got in his steel barrel to brave the rapids again about a week later. He hired Hill to help, and a good thing he did. His barrel got stuck in a whirlpool out of reach of those on shore. Hill tied a rope around himself and swam out to the barrel to redirect to shore. Leach emerged woozy, but alive. If Leach had hoped to grab back headlines, he’d made a miscalculation in hiring Hill.

On Leach’s direction and with a $15 incentive, Hill returned to the river later that evening to retrieve Leach’s barrel. When another riverman bet Hill $25 he couldn’t take the barrel the rest of the way through the rapids, Hill took him up on the challenge. He came out battered, bruised, $40 richer, and with some attention from the Niagara Gazette. In that news story, Hill told the reporter he could also travel down horseshoe falls in a giant rubber ball if given proper incentive.

Leach grabbed the attention back when he shot the rapids successfully in 1911 shortly before making his own plunge down the falls in his steel barrel. He billed himself the first man to go down the falls, which was true, though misleading. It was Red Hill who helped pull the barrel to shore after the plunge.

It didn’t take Hill long to find more river heroics. In the winter, as chunks of ice flowed from Lake Erie and jammed up at the foot of Niagara falls, and as temperatures dropped, an ice bridge would form extending across the river and joining the United States and Canada for about the length of a mile. This bridge became an annual destination for ice skating and sledding, and local entrepreneurs would set up shacks on the ice selling food, souvenirs. Think of a modern water park, but frozen. One source estimates a good ice bridge drew 20,000 people a day.

On February 5, 1912, Red Hill was on the ice bridge selling whiskey when the ice gave a loud crack and shifted. Soon, ice floes were moving downriver with dozens aboard. Most were able to scramble for safety, but four, two teenagers and one newlywed couple, remained stuck on sheets of ice heading toward the dangerous rapids. Hill, did his best to direct all to the Canadian side of the falls. Hill and friends successfully dragged teenager Ignatius Roth to safety saving his life.

The other three, however, remained stuck. Hundreds of spectators watched as the Stantons and the teenager Hecock traveled downriver on chunks of ice. Rescuers dangled ropes from the two bridges giving the stranded people a chance to grab on.

Hecock did grab hold of a rope, and onlookers cheered as rescuers hoisted him up in the air from the river toward the bridge. However, about halfway to safety, his grip gave out. The Buffalo Evening News reported: “The spectators turned sick as his body shot downward. The boy struck on his face and hands on the cake of ice. A large crimson blotch showed that he had been terrible wounded, but he struggled to his feet. A moment later the ice floe turned over and he disappeared.”

The Stantons could not take hold of the rope, and the people along the river watched as the couple held each other and drifted downriver to their death.

This was “The most heartbreaking tragedy in Niagara’s history according to the paper. Still, amidst the tragedy, Red Hill emerged as the heroic bright spot for his rescue of Ignatius Roth. For the second time, he received a medal for bravery.

Author Michael Clarkson named this period at the beginning of the twentieth century “The Age of Daredevil’s.” It’s the title for his book about the Hill family. It was also a time of a parallel though similarly man vs. nature -themed battle on the river for hydroelectric power. Nikola Tesla’s technologies were being leveraged for power generation in both the United States and Canada. The natural flow of the river started to change. In 1913 we also get this novelty song “Oh! What a Difference Since the Hydro Came” about how it’s harder to steal a kiss now that electric lights are all around the streets of Ontario.

(Song Plays)

Along with the leap in turn-of-the-century technologies came the outbreak of World War I, and Red Hill enlisted for military service. Hill’s departure to Europe grabbed a headline in the Niagara Gazette where he was also described as “…one of the best known rivermen in the district.”

In Europe, Hill was part of the gruesome battle of Vimy Ridge and endured chemical gas exposure and bullet wound. He spent the next 18 months in 12 different hospitals. A doctor told him he might have 6 months to live, sent him home, and suggested a warm, dry climate. Of course he returned to cool, damp Niagara Falls.

Soon after his return, the river called Red Hill to adventure again. On August 6, 1918, the tow line between a tug boat and a dredging scow snapped sending the scow down river toward the brink of the falls. The men aboard, James H. Harris and Gustave F. Lofberg, lowered the anchor, but couldn’t slow the boat. They tried a second makeshift anchor to no avail. Next, they succeeded in opening the compartments underneath the boat and were successful in catching against the rocky river bottom..

They sat in the middle of the swift moving current, too close to the falls for any boat to attempt a rescue. After several hours, and with daylight waning, the fire department succeeded in shooting a grappling gun out to the boat. The plan was to rig up a breeches buoy on a pulley, but as they sent the device out to the stranded scow, it drooped, dragged in the rapids, and tangled. Someone needed to go out and right the rigging. Red Hill volunteered.

About halfway out toward the scow, the pull system became jammed, and Hill had to pull himself along the rope by hand. The strain on his body in the dead of night, the glare of the firemen’s spotlights, and the river nipping at his legs, tired Hill, and returned to shore.

With rest, and breakfast, he regrouped and set out again. A crowd gathered to watch. Some started to sing the World War I soldier song, “It’s a long way to Tipperary” further digressing into “That’s the wrong way to tickle Mary,” a tune wholly incongruous with the perilous predicament.

(Neil Ellis Orts Singing)

After hours, Hill made it out to the boat and helped the men secure ropes. The three were successfully pulled out, though not easily. The rope bowed, at one point Harris was under water for nearly a minute. Nonetheless, the rescue had been a success.

Red Hill again received a medal from the Royal Canadian Humane Association. The scow stayed in the river, a visual reminder of Hill’s heroic feat. In 2018, the Niagara Falls Parks Commission commemorated the 100 year anniversary of the rescue bringing together several members of Hill’s family as well as the great-great-niece of Lofberg. In 2019, the scow made headlines again when it shifted and moved downstream, though it remains visible in the river today.

By 1920 when Charles Stephens, a barber from Bristol England decided he wanted to attempt to conquer the falls in a barrel, it was clear the man to talk to was Red Hill. Stephens, nicknamed the “Demon Barber” like the Sweeney Todd character, claimed to have kissed a lion in its den, shaved a customer in a lion’s den and parachuted from a hot air balloon. Hill, found Stephens likeable, and had him over for dinner at the house as the two plotted and talked about the river and barrel design.

Both Bobby Leach and Hill told Stephens he was playing a fool’s game. Still, if he were determined to make the attempt, Hill knew he was the best to help him, and it was Hill who closed Stephen’s barrel and pulled him into the river on July 11, 1920. His barrel “smashed like an egg shell on the jagged rocks at the base of the cataract” according to the Pensacola Journal. All that was recovered from his body was his right arm. It was an ending Hill predicted, but losing Stephens hit Hill hard.

1920 also brought prohibition to the United States, and with it, money-making opportunities for Niagara Rivermen like Red Hill. Rum runners could make a pretty penny smuggling liquor across the great lakes and crossing the mile-wide river made for a short, though sometimes dangerous trip. Hill, of course, knew the terrain well and had plenty of friends in the area. Others didn’t, the the papers from the time are filled with reports of shootouts, chases with the coast guard, and a pair Detroit rum runners swept over the falls.

Red also took in $5 for every body he took out of the river, and claims to have taken in 177 “floaters” in his lifetime.

With bootleggers, stunters, and rivermen seeking out the Red Hill to share secrets and trade news, it made sense that when Harry Houdini came to town to film “The Man From Beyond,” he found his way to the Hill house. Houdini picked Hill’s brain all he could, and contemplated a trip over the falls himself before deciding, perhaps because of Hill’s cautionary advice, the stunt was too dangerous. At this point in his career, Houdini had plenty of other ways to make money without risking death.

Meanwhile, Bobby Leach stayed in the papers with a parachute jump over the river with thousands looking on (though winds took him off course to a nearby field). He continued to talk about going over the falls again, this time in a rubber contraption (as was always Hill’s advice). In 1925, when several men talked about swimming across the Niagara River at the foot of the falls, Leach couldn’t help but hustle to the front of the pack. He hired Hill to follow him in his boat.

Leach’s first attempt was thwarted by the heavy wake of a Maid of the Mist boat, and Hill hauled Leach to shore. Leach made a second failed attempt, saving face by promising reporters he would go over the falls again. A week later, Hill himself made the swim in eleven minutes, becoming the first to do so, but more importantly, having reason to gloat after again stealing the limelight from his friend and rival.

Hill had no way of knowing that this would be the last time he’d be able to enjoy sparring with Leach. After years of dangerous stunts, Leech fell victim to what The Washington Evening Star called “One of Fate’s Queerest Pranks.” While touring in New Zealand, he slipped on an orange peel, broke his leg, and died from the resulting complications.

For years Hill and Leach had verbally sparred, but also together, they knew everything that went on at the river. They boasted, bragged, and ribbed one another whether at the Hill home, at Leach’s pool Hall. Together, they were the two sought out for a quote, advice, or retellings.

It likely would have been Leach and Hill, instead of just Hill, advising American Jean Lussier when he came to Niagara Falls with his giant rubber ball and announced he would be the next to conquer the falls.

Lussier, intent on being the first Amercian man to go over the falls, chose July 4, 1928 as his launch date. He kept the time and place of his departure secret so as to avoid police. 75-100000 spectators lined the river and planes circled overhead as Lussier climbed into his contraption wearing his red, white, and blue bathing suit.

Red Hill waited at the bottom of the falls and watched the giant ball plunge into the splash pool. It arrived battered, but whole, and Hill rowed out to it, hitched it to a rope, and pulled it to shore. Hill later said hauling the 900 lb vessel to safety before it drifted into the dangerous lower rapids, was one of hardests tasks he accomplished on the river.

Lussier emerged alive, and Hill ushered him away from the river to Hotel Niagara. There, Lussier held court with reporters who marveled at his daring. Several papers pointed out it was Hill who likely saved Lussier’s life by pulling him from the river before he entered the lower rapids.

Lussier, like Leach, did his best to capitalize on his daring feat by making public appearances and selling scraps of his famous rubber ball. When he ran out of authentic rubber bits, he passed off bits of used tires as Niagara Falls souvenirs. For the rest of his life, Lussier would tease reporters with a second trip down the falls, but it never happened. Like Annie Edson Taylor, he died poor.

With 1929 proving to be a slow year for Niagara Falls Daredeviling, in 1930, Hill ran through the lower rapids in a steel barrel on Decoration Day (Now known as Memorial Day). His son William Hill Jr., brother Charles Hill, and brother-in-law Edward Slogget were there to assist.

Later that year, George Stathakis came to town claiming he would be the next person to go over Niagara Falls. Unlike Leach and Lussier, Stathakis didn’t bring daredevil credentials with him. Instead, he brought a complex philosophy and a pet turtle whom he claimed could talk. A Greek immigrant, Stathakis worked as a cook in several restaurants and had recently come to work in Niagara Falls. He also wrote complex works of philosophy and claimed to have had adventures in past lives that included a visit 12,000 years earlier to what is now Niagara Falls. He planned to take his turtle, Sonny Boy, with him over the falls so that the turtle could recount the adventure if Stathakis himself were to die.

Though clearly lacking mental clarity, Stathakis did know enough to consult the famed river man Red Hill. Hill warned him about making the trip, and after inspecting Stathakis’s barrel, deemed it too heavy to succeed.

Nevertheless, seeing that Stathakis was set on making the attempt, just as Stephens had been, Hill agreed to assist. 20,000 people lined the river as Stathakis made his attempt, and his barrel made the plunge down to the splash pool with Red Hill and Red Hill Jr. ready and waiting to pull the barrel out of the river.

But, the barrel disappeared into the mist, The Hill’s waited, but nothing. Slowly, the spectators trickled away. Eventually, Hill did as well knowing that sometimes the falls took a body and swallowed it whole.

14 hours later, Canadian customs officials spotted the barrel trapped in an eddy and called the Hill’s. Red and his son rowed out and towed the 1-ton barrel to shore, and undid the 16 bolts holding it shut. Stathakis was dead. The coroner suspected he had been for ten to twelve hours. While the barrel had held together and Stathakis body looked largely unharmed, he’d run out of oxygen while caught behind the falls.

The turtle, Sonny Boy, survived, though contrary to Stathakis’s promise, the turtle failed to recount the trip. Hill took the barrel and the turtle home and set up a tented exhibit featuring the barrel, the turtle, and Hill’s own stories of danger and adventure on the river. At one point, Sonny Boy was stolen by opportunistic tourists. Hill, getting a tip on the identity of the theiving couple, gave chase, but gave up in Buffalo. The police caught up with the turtle thieves in Uniontown, Pennsylvania and shipped Sonny Boy back to Hill. The turtle died a year later and received some ink in local papers recounting his famous exploits. Hill, apparently, continued to exhibit him for a time afterward.

Now the owner of the 1-ton Stathakis barrel, Hill decided to put it to use with a trip through the lower rapids. William “Red” Hill Jr. headed up his support crew, and again, a crowd gathered on the river’s edge to watch.

However, this trip proved more treacherous than previous runs. The barrel got caught in a vortex, and tossed about in circles and up and down. While the river could sometimes smash you to bits, it could also hold on to bodies and keep them until their air ran out as it had done to Stathakis in the very same barrel and to Maude Willard in 1901.

Briefly, Red stuck his head out of the barrel, and yelled for help, but no one quite knew how to get to him. The fire department was on its way. There were discussions of using the aero car tram overhead and lowering a rope down. After 90 minutes of watching the swirling barrel, Red Jr., now in charge of his father’s rescue, tied a rope to himself, told two men on the riverbank to hold tight to the other end, and swam into rapids.

After twenty minutes, he reached his father’s barrel and tied the rope to it. Others were able to pull junior and senior out. Hill senior emerged haggard but proud, and there, medals pinned to his chest enjoyed sharing the spotlight with his son for onlookers, photographers, and reporters. After years of tagging along with his dad, after helping, and assisting, Red Hill Jr. had made his public debut with the river rescue of his father.

That would be Red Sr.’s last trip through the rapids, and he set up a souvenir shop showing off a collection of Niagara River barrels and billing himself as an attraction as well. Now, with Red Hill senior slowing down, developing heart problems and still feeling the lingering health effects of the war, his sons William “Red” Hill Jr. and Mayor Lloyd Hill who talked about shooting the rapids and going over the falls.

In 1942, William “Red” Hill Sr. died of a heart attack at age 54. The Niagara Falls community lost an icon, a hero who’d saved 28 lives on the river and the recovered the bodies of 177 accident and suicide victims. He’d been present for most every daredevil act on the river including four of his own trips through the rapids. Most importantly for the Hill family, they’d lost their patriarch.

Two Hill children, Red Jr. and Major, couldn’t let go of their father’s legacy. They carried his daredevil stunts into the next generation.

More on that, in part two.

Thank you for listening to The Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. If you’re enjoying the show, please write a review and tell a friend. Also, please consider connecting on social media. On Twitter and Instagram, I’m theodorecarter2. I’m also on Facebook as well, and there, you can join the public group “Niagara Falls Daredevils” to share your own stories and engage in discussions with others. This show is just me. There’s no funding behind it or other people behind the scenes. So, I’d love to hear from you to know more about what you enjoy, what you think I got wrong, or which daredevil I should research next.

The music you’re hearing now is from Holizna, slightly altered in parts for use in this podcast.

Thank you to Canadian Music Center for use of their recording of “Oh! What a Difference Since the Hydro Came”

Thank you to performer and author Neil Ellis Orts for his recording of “That’s the Wrong Way to Tickle Mary.” His website is neilellisorts.com. The background music is “Photography” by Alex Productions. {Photography by Alex-Productions | https://onsound.eu/ Music promoted by https://www.free-stock-music.com Creative Commons / Attribution 3.0 Unported License (CC BY 3.0) }