I live in Takoma Park and have several times engaged in unpermitted public art. I presume it’s for these reasons that people continued to ask my opinion on the controversial “movement sidewalk” near my house.

For background, Takoma Park’s Susan Comfort organized local youth to help paint colorful, cheerful messages and images on the public sidewalk. The city found her in violation of local law. Comfort made several attempts to get an exemption to the code including petitioning neighbors, confronting the city manager at city hall, and asking the mayor to intervene. The fight between Comfort and the city received a lot of media coverage until finally, city workers removed the paint.

Until now, I’ve chosen not to weigh in. I feared this issue would turn into a cesspool of acrimony. It did. However, several things have happened that pushed me to write this:

- Comfort asked me if I would support her efforts to fight the city, and I was evasive in my response.

- During the lively online debate about the sidewalk, mayoral candidate Seth Grimes linked to one of my old blog posts about a mural in Takoma Park.

- People are talking about public art and graffiti in ways I don’t like.

- Issues of access and privilege have been left out of the conversation.

- Media coverage revels in portraying this issue as another zany Takoma Park dispute without giving it the space it deserves.

Here, I have no word limit, so here goes:

“Bad Art is Better than No Art”

The above quote is from my grandfather, and it’s always a good starting point. Sometimes, works challenge this sentiment, but I’ve decided this statement is always true. I don’t know what I think about the mole mural along New Hampshire Avenue, but I love that I think about it every time I see it. It’s large, ambitious, and challenging.

The “movement sidewalk” was created by kids, and it was amateurish. Still, its presence made a statement. It said something about sadness during quarantine, salvation in youth, and a search for joy. This is not to say it had a right to exist. The mole mural went through a public process, and the painted sidewalk did not. Still, I applaud the defiant act of its creation.

Unpermitted Public Art Can Be Great

I love art that interacts with the public and lives outside of museums and galleries. It’s especially great when art is something kids and adults can touch, climb on, walk under, or be inside. Comfort’s sidewalk fits this description.

Unauthorized public art is often closer to the artist’s vision than the sanitized pieces that have been approved by municipalities and foundations. My favorite local example here is Clark Bedford’s wild art cars which you may have seen on the streets of Hyattsville or in the Takoma Park 4th of July Parade. I also love the Godzilla mural by Patrick Owens in D.C. off Rhode Island Avenue. It’s a good thing it’s on private property because there’s no way it would have been approved by the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities.

I like putting my work out in public because there are no gatekeepers and there’s no expectation of perfection. It’s satisfying to watch someone walk by something I’ve created and smile or take a picture.

For some people, the “movement sidewalk” brought joy. For some people, it did not. If it were on private property, this dichotomy could have existed for a long time.

Some People Won’t Like or Value Your Art

Several years ago, I put large tentacles on various traffic boxes in D.C as part of a project titled “Tentacle Tuesday.” One online commenter was particularly upset by this project.

There are plenty of people who think Bedford’s cars are an eyesore and probably some who don’t want to look at Mothra and Godzilla destroying Japan while walking down Rhode Island Avenue.

I used to work at a school a few blocks from an enormous Kelly Towles mural in the Palisades neighborhood. The mural became a walking destination for me, my colleague, and our second-grade students. One year, the mural was gone. My colleague met Towles and asked him about this. He said several neighbors didn’t like the mural and asked that it be removed. My colleague said Towles appeared nonplussed by this and ready to move on with new work. This story makes me like Towles more.

Recently, a property owner painted over a mural by Eric B. Ricks near the Takoma metro. I didn’t see a single mention of it on any online neighborhood forums. I’m not aware of any petition, exemption, online kerfuffle, or resulting media coverage. How many people noticed the mural was gone?

Some people didn’t like the paint on the sidewalk in front of Comfort’s house, and I understand why. It wasn’t as good as the work by Bedford, Owens, Towles, or Ricks. The “movement sidewalk” was always going to be temporary.

Breaking the Law Can Be Beautiful

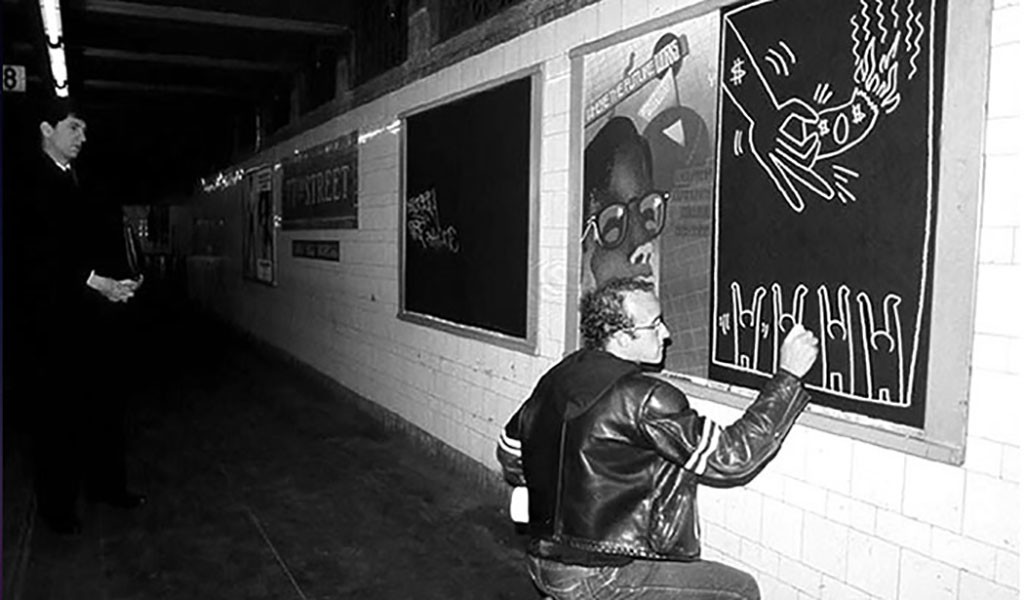

Keith Haring started out drawing in subway stations. Jean Michel Basquiat started out by tagging “SAMO” across New York City. The aforementioned Kelly Towles started with graffiti too, And of course, there’s Banksy.

Taking risks to create art can be part of the art itself. Particularly in the cases of Haring and Basquiat, there was an almost desperate need for these marginalized people to be seen.

Please think of this when you walk under the Carroll Avenue bridge on the Sligo Trail. The graffiti (yes, I’m calling it graffiti) there isn’t very good (yet), but there’s a youthful yearning that I love, and I want to hug all of these kids.

Still, I understand why the city keeps painting over the spray paint, and I feel bad for the city workers unwillingly drawn into this dance. Those naughty kids shouldn’t be spray painting on public property! Likewise, I understand why the City Manager, confronted by Comfort at city hall, responded to the complaint, issued a violation, and followed through with removing the painted sidewalk.

How to Break the Law with Kids

When I met Nancy Shia, former ANC commissioner, activist, photographer, long-time Adams Morgan resident, and all-around badass, she told me a story about being stopped by cops while wheat pasting anti-W. Bush art with her four-year-old granddaughter during the lead up to the second Iraq War. I could make lots of arguments as to why this makes her a fantastic grandparent.

I don’t have the stomach for danger that Shia does. My work is always temporary. However, like Shia, I have involved kids in some of my unpermitted projects. They know that I’m taking a risk, that the cops could shut me down or that whatever I put up could be gone in a few hours. They’ve heard me talk about the value of what I’m doing as well as the risks.

Comfort consulted city council member Cindy Dyballa before starting her sidewalk movement, and Dyballa told her that it would only be a problem if someone complained. This sounds like a fine starting point to me, and I hope that when Comfort involved these kids, she told them their work had value, that they were taking a risk, and that their work could be gone in an instant.

The argument that the big bad city made kids sad by power washing the sidewalk doesn’t hold water with me. The painted sidewalk had a good run, and the local government did exactly what it was supposed to do. There’s a civics lesson here too.

Privilege, Art, and Graffiti

When I put up unpermitted projects in public, I am protected by my identity. As a middle-aged white man who sometimes has a kid in tow, I know that if confronted by police, I can likely talk my way through it, take my artwork, and go home safely. This is not the case for people of other identities.

Often, the distinction between what we call art and what we call graffiti has a lot to do with the identity of the artist.

Comfort’s painted sidewalk is in a largely white neighborhood made up of stand-alone houses. She clearly feels she has access to her city council member, city manager, and mayor. The project has received coverage from WJLA, NBC4, DCist, and Bethesda magazine.

Comfort’s request for an “exemption” hit me wrong. It was a request for a different set of rules. I don’t have a problem with Comfort violating a city ordinance, but I do have a problem with her unwillingness to abide by the law once called out. Outrage around this particular code violation and the resulting media coverage seems to have a lot to do with the perpetrator and the fact that it happened in Ward 2.

The Process for Public Art

One complaint repeated in this sidewalk debate has been a lack of process for the approval of public art. I will say that for myself, the reason I often don’t get permits for projects is that there isn’t any permit that fits what I’m trying to do. Trying to explain to DC Parks and Recreation that you want to put 100 illuminated duck sculptures in a field is confusing for everyone. And no, I don’t know how to design a traffic impact assessment.

Still, many people are working hard to promote art in Takoma Park, and we should recognize them. The Takoma Foundation offers grants every year. The city of Takoma Park often solicits proposals for public art. The Arts and Humanities Committee often has vacancies, so those fired up about process should sign up. Main Street Takoma hosts several events every year to promote local artists and in my experience, is open to new ideas.

These opportunities don’t fit all projects. However, each of these organizations offer a process for the creation of public art, and we should be grateful for them.

When Art is Met with Apathy

As I said earlier, when I put work out in public, some people enjoy it and some do not. However, the majority of people who pass by don’t notice it at all, even when the work is big, and in my opinion, unmissable.

Often, when I mention a mural or a piece of local art that I consider a landmark, I’m met with a blank stare. To me, not noticing public art is the greatest sin. I would rather hear outrage than ambivalence.

For this reason, I’ve enjoyed the controversy over the painted sidewalk. However, I want people to care as deeply about some of the other work in our area, both commissioned or illegal, and feel passionate about it one way or the other. Talk to me about the mole mural. Show me the plastic dinosaurs your neighbor put in their flower pot. Tell me about the dirty limerick you saw written in the bathroom stall.

In Takoma Park, we claim to care deeply about art. However, sometimes I think this is a nice thing to say, an abstract concept that fits with a liberal idealism, more than a genuine sentiment. A lot of people miss what I think is unmissable.

This, in the end, is why I chose to write this. I couldn’t stand how much attention this particular painted sidewalk received while residents don’t notice or care about so many other works of art.

Please visit Clarke Bedford’s house in Hyattsville or have lunch underneath Godzilla. Buy some original art at the street festival. Go to a museum. Or, better yet, create something weird and leave it in the spot pictured below. Make sure it’s easy to remove if the city decides to do away with it, and don’t complain to me if it disappears. The “movement sidewalk” is gone, but there are other things to appreciate and to create.