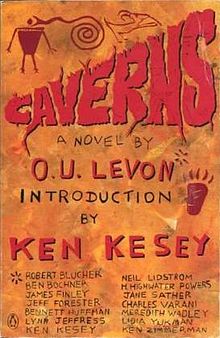

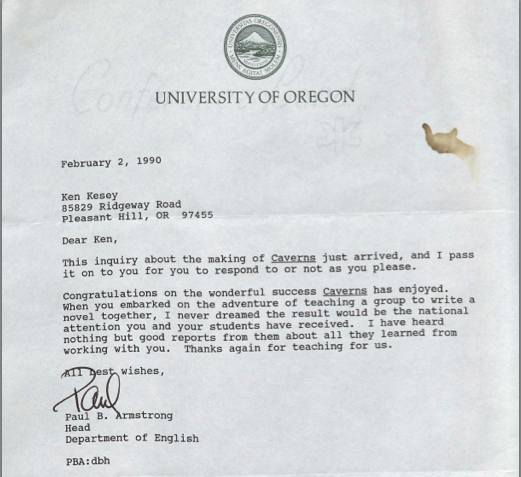

During the academic year of 1987-1988, Ken Kesey taught a graduate-level creative writing class of thirteen students at the University of Oregon. He charged the group with producing a full-length novel in one school year, which they did, publishing Caverns under the name O.U. Levon (Novel University of Oregon backwards) in 1990.

It is my intent to interview each living author about the project and what they learned from Kesey. I outline the project in more detail in my initial posting. Here is list of all living authors and links to to past interviews:

Ben Bochner, James Finley, Jeff Forester, Lynn Jeffress, Neil Lidstrom, Jane Sather, Charles Varani, Meredith Wadley, Lidia Yukman, and Ken Zimmerman.

Robert Blucher’s interview is the eleventh I’ve published.

What is your life like now? Are you still writing?

My life today is very disorganized and chaotic, as life can be when one’s attention is not consumed by a full-time job. I play on a tennis team that came in second at the play-offs, take classes in jazz harmony and songwriting at the community college, and get to know young people who like the same kind of music I like.

I had a frenzy of writing in the three years after the class, two published stories and a one act play that was produced locally. Then I got a full-time teaching job and started playing in a blues band which diminished my writing energy for a while. Since I retired, I’ve written a few short stories and a play. I’m still plagued by the need to write dialogues and scenes that come to me in the middle of the night. I get up, type into the computer for an hour, and sometimes remember to save it all on my hard disk.

What do you remember most about the process of writing a book with thirteen other people?

I enjoyed working with the other students. They were excellent writers and fun to hang out with, but I was frustrated when things that I thought were good writing were changed or deleted. The group mind can produce good comedy and TV sitcoms, but I think serious fiction requires a unity of vision that can only come from a single mind.

I missed some of the field trips and the late night editing sessions because in addition to the class, I was teaching two computer science classes. I was pooped after the Caverns class and went home grade papers and prepare for the next day’s teaching.

I think Kesey’s plan was to give us practical writing experience and a feel for how to persevere through a long writing project. He worked hard to plant the seeds for the plot of a journey novel, talking about Spanish explorers, a mysterious meteor that fell in Oregon and showing us movies after class. I still remember sitting with Chuck and Ken and Bennett in Kesey’s living room, watching the Herzog movie, Fitzcarraldo, about a Spanish conquistador’s journey up the Amazon.

What did you learn from writing Caverns?

The plot debates during the first term reminded me a lot of a time when I was on a union grievance committee writing a formal grievance — a lot of passion, but slow progress. The editing process was good for me because it gave me a different perspective on writing. I tend to write in a Hemingway-like, terse, non-adverbial style with inadequate setting of scene. I was struck by the difference between my style and Kesey’s. I became more aware of texture and rhythm. Kesey had a gift for creating long, rambling, rhythmic descriptions that brought a scene to life, slowing down time and expanding the moment.

I remember some of Kesey’s comments about writing: “It’s just as much work to write a bad novel as a good novel” and “You’ve got to jump off the diving board without looking to see if there is any water in the pool.”

What stands out in your memories of Ken Kesey?

Kesey treated us as if we were members of his family. I remember his stories about the Merry Prankster days, but he also had an Oregonian side. He reminded me of the people I met growing up in a small town in Central Oregon. He was a down to earth guy with a gift for telling stories and entertaining people. If he hadn’t become famous, he still would have been the life the party wherever he was.

I ran into him at a Eugene Symphony concert a few years later and we talked about Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto, which he remembered from the Marilyn Monroe movie The Seven Year Itch. A year before he died, I saw him at my doctor’s office, and it was like running into a neighbor or a high school friend. He asked me how I was doing. Not a word about his illness.

How do you feel about the book as a finished product?

I have met people who found the book to be an entertaining adventure novel, but for me, it didn’t have enough character development. Although there are good scenes and good spurts of writing in Caverns, there were probably too many cooks in the kitchen for it to be more than entertainment fiction.

How would you describe Kesey’s method for organizing the class?

I feel that Kesey’s method of organizing the class was inspired and could be used as a way to introduce the elements of fiction to classes of beginning high school or college writers.

After the novel came out, Charlie Varani, Jim Finley, Bennett Huffman and I compressed Kesey’s method into a twenty minute group writing exercise and presented it at conferences of English teachers in Portland and Spokane. A couple of years later, I taught two community education classes called “Collaborative Fiction” using the method.

The big advantage of collaborative writing over traditional workshop classes is that the social aspect seems to make the process more fun. Students feel less pressure. They feed off of each other’s ideas and get a chance to let their sense of humor run wild while they are getting experience constructing plot and editing.

I’m a little bit sad that your series is over. It took me back to the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, when a man I never met (and only talked to once on the phone), was so very influential to my writing and worldview.