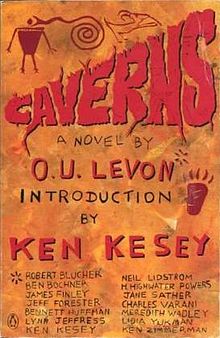

During the academic year of 1987-1988, Ken Kesey taught a graduate-level creative writing class of thirteen students at the University of Oregon. He charged the group with producing a full-length novel in one school year, which they did, publishing Caverns under the name O.U. Levon (Novel University of Oregon backwards) in 1990.

It is my intent to interview each living author about the project and what they learned from Kesey. I outline the project in more detail in my initial posting. Here is list of all living authors and links to to past interviews:

Robert Blucher, Ben Bochner, James Finley, Jeff Forester, Lynn Jeffress, Neil Lidstrom, Jane Sather, Charles Varani, Meredith Wadley, Lidia Yukman, and Ken Zimmerman.

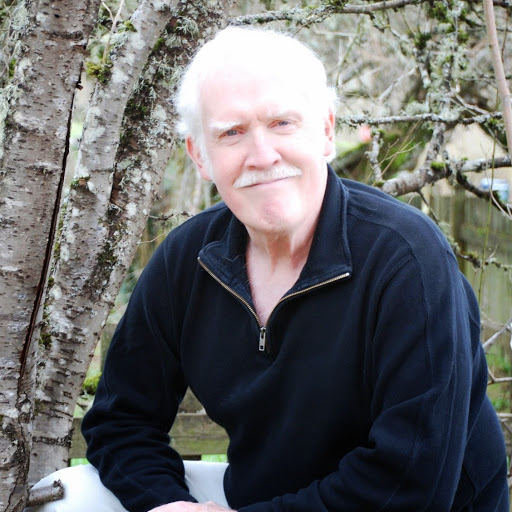

Hal Powers’s interview is the eighth I’ve published. In each case, I gave the interviewee wide latitude as far as what questions he/she answered and in what format. Hal made use of this latitude and chose to focus on the two questions he found the most important and relevant.

What is your life like now? Are you still writing?

What is your life like now? Are you still writing?

At age 71, I sometimes think of myself as a spin-off of the real-life character Chuck Kinder, a writer and poster child for any combination of three serious creative disorders affecting wordsmiths: writer’s block, procrastination, and hypergraphia, the midnight disease. Kinder (1972-73), like Ken Kesey (1959), was a Stegner Fellow at Stanford University and the role model for one of his student’s novels, Wonder Boys, by Michael Chabon. Professor Grady Tripp in Wonder Boys rightfully wears the loose sleeveless mantle of Kinder, who in real time spent nearly 20 years producing an unwieldy novel of over 3,000 pages which, under the thumb of an editor, became a reasonable 358 leafs entitled The Honeymooners in 2001, an admitted romans à clef based on his friendship with fellow Stegner Fellow, Raymond Carver.

After the Kesey experiment, I began teaching Conversational English in Japan, retiring in 2008. In contrast to the inordinate amount of money I earned, my teaching load and responsibilities were ridiculously light. It was then, in my self-imposed monastic lifestyle, that I began to seriously focus on reading all the great and lesser works that I had under deadlines often skimmed in college, and it was in my Nagoya apartment that I discovered and recognized my writing voice referred to in quantum detail – some believe tediously and inaccurately – in Caverns and Voices, a submission to our group’s later intention of following up the Kesey project with a book illuminating our experience.

And then I wrote.

I began work on a collection of inter-connecting short stories – pieces that might be able to stand alone while also supporting a novel-length format – The High Rock Stories, featuring an aging dilettante who in his sixties, with a worn-out Remington typewriter, returns to his crumbling mill town with dreams of solving an age-old mystery while recording for posterity some of the stories he learned from and about its townspeople before he took to the road right out of high school in 1961 in search of Kerouac-ian adventures. One would have similar difficulty locating the restless line between Chuck Kinder’s confessed roman à clef and my approach to story writing since we both admittedly draw more heavily from actual experiences rather than pure imagination – if there really is such a thing – during the creative process. All of which flies in the face of a Kesey dictum: Don’t write about what you know.

In exile as an ex-pat, I decided that either Kesey had been misunderstood or we had been misled by him. I chose the latter. I believe the deeper we scratch our psychic wounds, the closer we can get to understanding what it truly means to be human. Profound rich truths, like one’s writing voice, spurt crimson upon blank pages from ruptured arteries, not from leaking the tired, grey-tinged blood from surface-level veins. His advice was probably a calculated, preemptive action designed to prevent us from setting our experimental novel on a college campus with a stock of frat-brothers-sorority-sisters, hot co-eds and self-indulgent professors that could have echoed of the page the Animal House story filmed in Eugene environs and on the UO campus just some twelve years earlier.

Don’t write about what you know. If that’s good advice, then how do you square the great successes of Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion with his admitted experiences as a guinea pig for psychedelics at Menlo Park Veteran’s Hospital, his stint working at the state veteran’s hospital, and from living in Eugene, the hub of so many logging communities rimming Eugene and brimming with logging lore? As all great writers, Kesey fundamentally wrote about what he knew first hand; in the case of Caverns, our great mentor simply thought it best to have his hands firmly on the steering wheel of his busload of neophytes.

Like Grady Tripp, AKA Chuck Kinder, I have suffered wounds many times by killer questions fired unexpectedly at me about my writing. They zing and whiz, come at the most absurd moments, like the sniper’s bullet that killed Lew Ayers in All Quiet On The Western Front as he reached his hand out of the muck and mire of the trenches toward the beauty of a butterfly. I, too, wear the mantle of a writer, am certified by an MFA in fiction, credited as a co-author of Caverns, have won a couple of minor awards in fiction and journalism, have mentored and taught novices in composition and story, and I talk-the-talk fairly well, which means my cloak is emblazoned with a powerful electro-magnetic target that sucks every errant missile my way, whether by foe or friend: Yer a writer? Whaddaya write? How’s that novel of yers going? When ya gonna finish? And the most recent and troublesome questions by Theodore Carter in this blog:

Like Grady Tripp, AKA Chuck Kinder, I have suffered wounds many times by killer questions fired unexpectedly at me about my writing. They zing and whiz, come at the most absurd moments, like the sniper’s bullet that killed Lew Ayers in All Quiet On The Western Front as he reached his hand out of the muck and mire of the trenches toward the beauty of a butterfly. I, too, wear the mantle of a writer, am certified by an MFA in fiction, credited as a co-author of Caverns, have won a couple of minor awards in fiction and journalism, have mentored and taught novices in composition and story, and I talk-the-talk fairly well, which means my cloak is emblazoned with a powerful electro-magnetic target that sucks every errant missile my way, whether by foe or friend: Yer a writer? Whaddaya write? How’s that novel of yers going? When ya gonna finish? And the most recent and troublesome questions by Theodore Carter in this blog:

“What is your life now? Are you still writing?”

There’s only one acceptable definition for the word writer: A writer is one who writes, a definition which is not predicated upon either one’s degree of public success stemming from one’s list of publications. In its most simplistic form, it means for me to be actively engaged in the process of putting words on a page. It means to be active in some phase of a creative process dealing with words – and the key word here is active – whether it be reading, note-taking, brainstorming, contemplating or typing, any activity that leads the creator or audience to an image whose essences is based on word play. It means for me to be actively engaged in story-telling – whether fiction or not – poetry, song lyrics, letters, informative or entertaining essays or memorials or tributes, journaling, or just plain jazzing around, all forms of the written word specific and personal to my oeuvre as a writer.

What is your life like now? Are you still writing, asks Mr. Carter. I occasionally write poems as I have over the years whenever I fell in love or had my heart broken or found myself beaming an illegal smile. For the last two years I have been working with my brother, a talented guitarist and singer in Syracuse, New York who finds a way to musically adapt and express my words as we work together to create a collection of songs for a CD.

As old school as it sounds, I write letters. Long-paged true epistles from the heart and head. Whether or not it’s a missive to a Miss concerning the ambitions and complications of love, or a forwarding of a flaming kite to traffic court appealing a parking ticket, I labor mightily at achieving accuracy, clarity, creativity in text and tone. I may not always win my pleadings to love or law, but I am usually pleased, sometimes even amused at my dedication to, and honor of, the printed word.

I have to my credit a handful of essays written in the last few years that attest to my dogged pursuit of trying to make sense out of the art of writing, my life, the passing-over of loved ones, and almost daily I scratch on sticky notes, napkins, yellow pads, and grocery receipts written fragments both brilliant and mundane and eventually get them transcribed into my treasured cyber notebook which takes up where my shelf of spiral bound paper equivalents left off quite a few years ago.

My electronic journal houses my Fictionary, a compilation of departments dedicated to language, dialogue, descriptive terms, contractions-expletives-interjections and samples of technique and dialogue, anything that may support my writing projects. The bulk of my journal, however, comprises my two prospective novels with the working titles: Revenge, which grew out of my collection of shorter pieces, The High Rock Stories, and overshadows them in terms of length and its state of incompleteness, and Silvia Steel, the Silver Angel: the almost true story of a near-life event, a semi-historical story about barnstorming after WWI. Like Chuck Kinder and his novel, The Honeymooners, these two works of mine have absorbed most of my creative energy for years. Almost daily I rob and steal from other writers, film, drama, conversations, personal observations, any medium of written or spoken word, and, notes in hand and inspired, I feed the essence of those purloined fragments, with my own personalized twists, into ever-expanding character profiles and plotting. My two protagonists in Revenge, Bobby Draygo and Will Hardesty, therefore, are now as real and alive to me as family, as are Silvia Steel and The Boy who believes in her.

This is where Charlie Rose, Bill Moyer, or those less luminous ask: But is that writing…real writing? Yes, I answer, under the definition at the beginning of this conversation, it’s writing. Writing, as the gurus like to say, is a process, and the snail-paced work I have been doing for years is the heart of my particular process. I am actively putting words on the page and am constantly creating and living with my stories. That’s writing in its simplest form. What I am not doing at this point in my life is sharing or publishing my work because, for now, the pace and load of work itself seems sufficient.

Kesey once told us cavers to not disparage the blue hair ladies of the local writers circle because writers, all writers, face a most difficult challenge, and they and our present luminaries need our empathy and support, the sub-text of which is that public success is not the truest measure of a writer. Writers not blessed with abundant talent, or the pluck and luck, or the will for whatever reason, that leads to publication often face and overcome much more formidable obstacles than the more gifted and renowned.

Great last paragraph. How we define ourselves is not always measured in commercial success. But the dedication towards that end , and the energy needed to try and improve each and every day, certainly is a great yardstick.

Hal,

So good to “hear your voice” again. I remember it well and glad it is good as ever. Will take some time to follow up on the longer link provided.

As for illegal smile, times like this at the end of a string of fifty below zero days, that damn near every smile is illegal, or ought to be at any rate.

Miss you friend,

Jeff