Listen here. Full transcript:

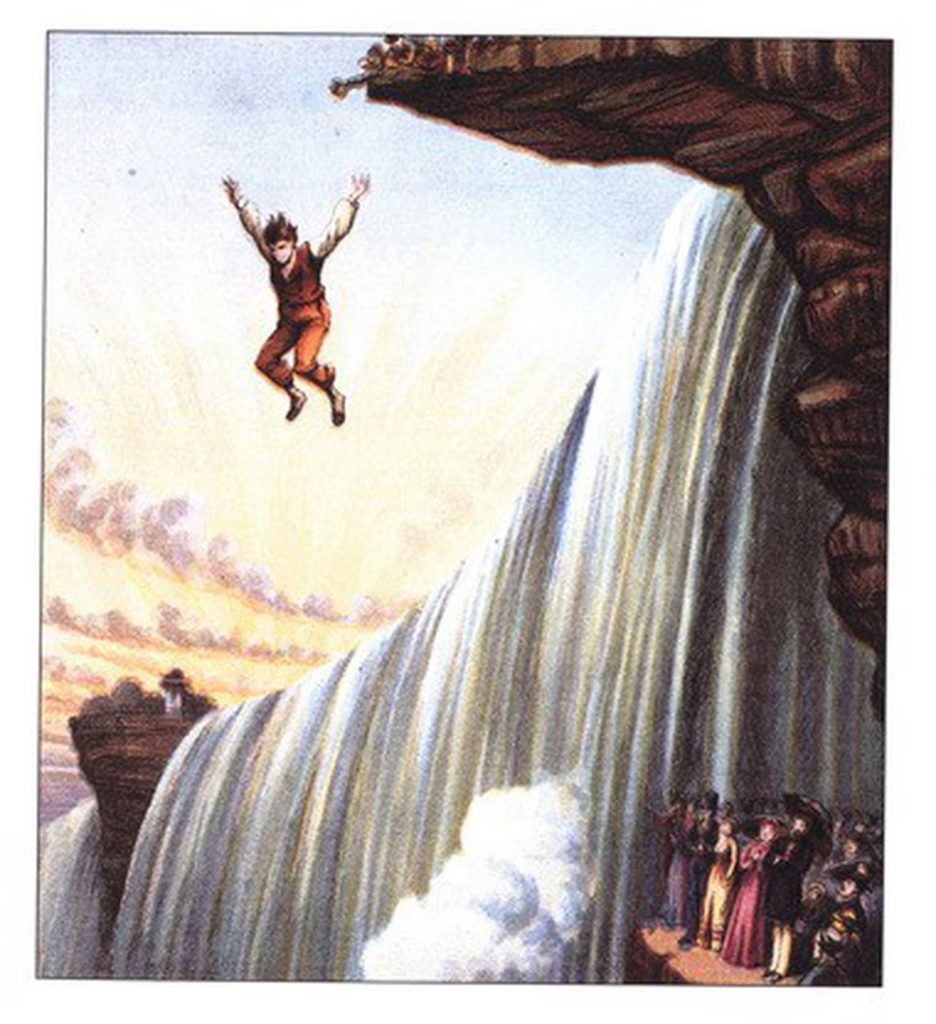

Sam Patch, the Jersey Jumper, the Yankee leaper, reached celebrity status in the early nineteenth century for his death-defying leaps from great heights including two jumps over Niagara Falls. His public appearances drew thousands, upset the sense of decency of the high-minded, and made great news copy at a time when newspapers were growing in number and circulation.

Sam Patch’s short but eventful life came to an end in exactly the way many expected it to. He died after attempting a second leap at The Upper Falls on the Genessee River, this time from a platform perched 120 feet above the river below. Part one of this two-part episode told the story of his most famous jumps, his pet bear, and his growing celebrity. This episode will examine Patch’s second life, his ascension into myth after his death, and how he continues to live on in songs, poems, and books.

Welcome to the Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. In this podcast, we’ll examine the bravery, stupidity, hubris, and eccentricity of people who have attempted daring feats at Niagara Falls. My name is Theodore Carter. I’m an author whose novel research went too far, and I got swept up in the current of stranger-than-fiction stories surrounding Niagara Falls. Now, I’m putting that research into this podcast.

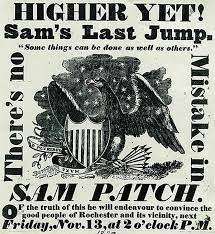

Onlookers present at Sam Patch’s second and final jump at the upper falls on the Genessee River reported that he was drunk, or at least more drunk than usual. While typically he put his arms at his side after a leap and plummeted down toward the water arrow straight, this time he tilted and hit the river awkwardly. The crowd waited for him to emerge from the river, to defy the odds once again, and proclaim, “There is no mistake in Sam Patch” and “Some things can be done as well as others,” but he did not.

The plunge pool below the falls roiled, but Sam failed to appear either alive or dead. Without a body, rumors spread. Perhaps he’d faked his death, scrambled to shore unnoticed, and would at some point reappear having pulled off the most remarkable stunt of his career. Others took this opportunity to again opine about Patch’s ghastly and distasteful antics. He became the subject of cautionary sermons in Rochester and mocked for a vanity that led to his death.

And, just as rumors continue that Elvis and Tupac faked their deaths, there were many who refused to believe Sam Patch had died, especially without evidence of a body. People claimed to have seen him or to have heard that others had seen him, in Rochester, in Manhattan, and elsewhere. An announcement appeared in the New York Post on Novermber 30th with the headline “Sam Patch Alive!” The text, supposedly written by Patch himself included a heavy sprinkling of his catch phrase, “make no mistake, I am the real Sam Path.” as well as these lines: “some things, you see, can be done as well as others; and I am resolved to let the world know that I am still alive and kicking. It was a capital hoax though, wasn’t it?

Patch had been scheduled to give a talk at a tavern on December 3rd, and many showed up on the appointed day thinking he’d show. He did not. Adding to the confusion, several newspapers published a story about Patch’s body being found in the Genessee River, but these reports proved to be false.

Then, in March of 1830, approximately six months after Patch’s jump at the falls, Silas Hudson a hotel worker, walked his employer’s horses to the river to drink at the mouth of the Genessee near Lake Ontario. The water surface had frozen, so Silas kicked through the ice with his boot. When he did, the body of Sam Patch bobbed to the surface. The body was clothed in the black silk waist sash and white Rochester band pants he’d worn during his final jump six miles away.

However, even this failed to put the matter to rest. Nathaniel Hawthorne came through Rochester several years later, and in an 1835 essay wrote about locals still denying Patch’s death.

Strange as it may appear–that any uncertainty should rest upon his fate, which was consummated in the sight of thousands-many will tell you that the illustrious Patch concealed himself in a cave under the falls, and has continued to enjoy posthumous renown, without foregoing the comforts of this present life.

Like many American celebrities, from blues musician Robert Johnson to James Dean, Sam Patch became more popular after his death. A Library of Congress newspaper search turns up just a few mentions of Patch during his lifetime, but nearly three hundred mentions of the name in the second half of the 19th Century.

Andrew Jackson named his new horse Sam Patch in 1833, four years after the death of the human daredevil Sam Patch. Historian Paul E. Johnson delves deep into the importance of Sam Patch’s legacy at the time of Jackson’s populist rise. Patch was a symbol of rugged individualism, a poor man who rose to fame out of sheer grit and gusto. Johnson also points out that this period in American history also saw a boon in newspapers and printing, which no doubt made myth-making easier. Sam Patch’s became part of everyday language, a replacement for curse words, such as “where in the Sam patch did I put my keys” and his saying “some things can be done as well as others,” stuck around as well.

Nationalism and American myth-making were having a moment in the middle of the 1800s. Davey Crocket died within a few years of Patch, and his life began to take on legendary status shortly afterward. Johnny Appleseed had become a mix of fact and fiction before his death in 1845, and afterward, he grew into a folk hero. Paul Bunyon stories began circulating around 1860 in logging bunkhouses. John Henry was born in 1848. All of these stories are important to American identity.

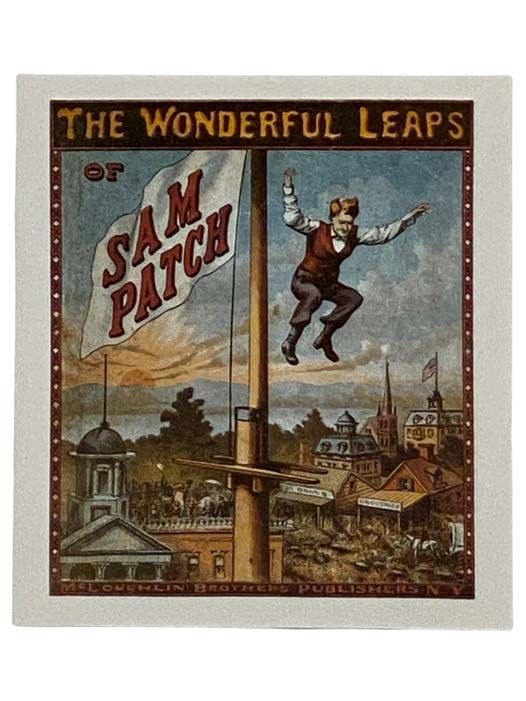

In 1875, the McLoughlin Brothers published the children’s book, “The Wonderful Leaps of Sam Patch” featuring some fantastic full-color illustrations. The book was rereleased in 2012 by Applewood Books, a publisher that revives old titles for new generations. In describing what makes a book worthy of a rerelease, they state

The story must raise our hopes, increase our fears, make us laugh, make us cry, cheat death, bring new life, teach us, touch us, give us a reason to cheer for the good guy and root against the bad. It must take place in our imagination. It must be carried with us long after it is read. It must imbed itself in heart, mind, and memory. It must be broadcast to others or it will fade.

No doubt, Sam Patch’s story is a great fit.

Though Sam Patch did not become a household name on par with some of these other American myths, his legacy has endured. Sure, he’s more firmly in the fabric of the history of New York state than in the country as a whole. Even so, still today, people continue to tell stories about Patch and to write poems and songs about him.

Poet Cornelius Eady, a National Book Award Finalist, Pulitzer nominee, and the recipient of numerous other impressive distinctions penned the poem “The Death of Sam Patch.” I love it because it references Icarus and the William Carlos Williams poem included in part 1 of this episode. He also turned Patch’s story into a song.

Cornelius Eady’ Song Plays

What I think is unique about Eady’s telling here is how he hones in on the presumed loneliness of Patch’s jumps as he mentions the bloodthirsty crowd and false friends cheering. I also love his line you’re about to hear about the platform wobbling like a dancing bear, an obvious allusion to Patch’s famous pet. Also, “rising like a ghost in the air,” because storytelling is one way to preserve ghosts.

It’s worth noting that Eady grew up in Rochester, New York.

Rochester band “Coffee and Beer” recorded a great Sam Patch song too.

O’Connor: “Coffee and Beer started out as a group, me and my buddies Ben and Lief. We added a couple more members along the way, but it just kind of started out as buddies playing in the basement. As much as we enjoyed playing out, we really liked songwriting.”

That’s Coffee and Beer band member Jim O’Connor.

Coffee and Beer’s “Sam Patch” plays.

O’Connor first learned about Sam Patch from a TV sketch comedy show.

O’Connor: “You never know with those types of shows, but I decided to do a little bit of research because I heard Rochester, New York. Everyone wants to leave a mark in some way, I believe, whether it’s historically or the people you love, but the idea to do that by jumping off waterfalls and bows of ships speaks to the person that he was but it also speaks to the time period and what people where entertained by.

If given legal permissions, I could go on reading other people’s poems and playing their songs. I could tell you about subtle notes in the Sam Patch Porter released by Rohrbach Brewing Company in 2019, but the point is, Sam Patch has remained part of American storytelling, American art, for nearly 200 years.

Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote about Patch’s legacy, and I’ll let his words be the end, the final plummet in this two-part episode.

He will not be seen again, unless his ghost, in such a twilight as when I was there, should emerge from the foam, and vanish among the shadows that fall from cliff to cliff. How stern a moral may be drawn from the story of poor Sam Patch!

Why do we call him a madman or a fool, when he has left his memory around the falls of the Genessee, more permanently than if the letters of his name had been hewn into the forehead of the precipice? Was the leaper of cataracts more mad or foolish than other men who throw away life, or misspend it in pursuit of empty fame, and seldom so triumphantly as he?

That which he won is as invaluable as any, except the unsought glory, spreading, like the rich perfume of richer fruit, from virtuous and useful deeds.

Hawthorne’s words are pretty great, fancy, and beautiful. But, I made this podcast for you, and I’ve tried to keep it simple because some things can be done as well as others.

O’Connor: “I don’t think it’s a great catchphrase in that regard. How about you? What do you think?

Thank you for listening to The Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. If you’re enjoying the show, please write a review and tell a friend. Also, please consider connecting on social media. On Twitter and Instagram, I’m theodorecarter2. I’m also on Facebook as well, and there, you can join the public group “Niagara Falls Daredevils” to share your own stories and engage in discussions with others. This show is just me. There’s no funding behind it or other people behind the scenes. So, I’d love to hear from you to know more about what you enjoy, what you think I got wrong, or which daredevil I should research next.

Thank you again to Cornelius Eady, Jim O’Connor, and Coffee and Beer for the use of their songs. The music you’re hearing now is from Holizna, slightly altered for use in this podcast.

While I consulted many sources in the creation of this podcast, I’d like to mention two specifically because they were the best and the two I referred back to most frequently. The first Is Paul E. Johnson’s book “Sam Patch, The famous jumper.”

The other is Richard M. Dorson’s article, “Sam Patch: Jumping Hero.”