Listen here. Full transcript:

Annie Edson Taylor, a Victorian-era dance and etiquette teacher, strode gracefully toward the riverbank in her long black dress and wide-brimmed hat. She did her best to look stately as she climbed into the skiff along with notorious river riff-raff Fred Truesdale, who had been arrested just weeks before, and William Holeran, a replacement for another riverman who’d decided at the last minute he didn’t have the stomach for the job ahead.

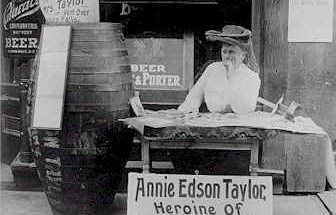

It was her 63rd birthday, or 43rd if you go by what she told the press, and 200 friends, reporters, and gawkers stood on shore wishing her well and waving goodbye as she took her place in the boat. Taylor smiled, waved back, and assured onlookers of her resolve. She also handed a newsman a letter meant for her sister in the event of Taylor’s death.

Taylor and her crew had moved their departure time up an hour seeking more favorable weather conditions, but also to get out ahead of police who had repeatedly warned them if they were to carry out this stunt, Taylor would surely end up dead, and those who’d helped her would face charges of manslaughter.

Next, Annie Edson Taylor, Fred Truesdale, and Billy Holleran glided through the water with the custom-made barrel in the back of the boat. At Grass Island, they stopped and set the barrel in shallow water.

There, for the sake of decorum, Taylor asked the men to turn their backs to her as she removed some of her finery, and climbed backwards into her barrel. She secured herself inside using specially made leather straps. Holleran and Truesdale loaded pillows into the barrel as well to help soften the impact as the barrel crashed against water and rock. They pushed in air with a bicycle pump, and then, finally, after months of preparation, the men sealed Taylor into her barrel, and sent her down the Niagara River toward the Horseshoe Falls.

“I felt it was easier to face death than it was to live,” she later wrote and she approached the edge of the Falls certain she’d either die or set course for a new, more prosperous life.

Welcome to the Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. In this podcast, we’ll examine the bravery, stupidity, hubris, and eccentricity of people who have attempted daring feats at Niagara Falls. My name is Theodore Carter. I’m an author whose novel research went too far, and I got swept up in the current of stranger-than-fiction stories surrounding Niagara Falls. Now, I’m putting that research into this podcast.

Annie Edson Taylor is the Niagara Falls daredevil everybody knows, even if you don’t know her name you’ve seen her famous stunt imitated and parodied. She conceived of the audacious, seemingly nonsensical spectacle of going over Niagara Falls in a barrel. Now, this idea is a trope repeated in a Harry Houdini movie, numerous political cartoons, a Woody Woodpecker episode, Bob Dylan lyrics, children’s books, a musical, and a made-for-TV movie. Going over Niagara Falls in a barrel is pure daredevil Americana, like jumping cars on a motorcycle or wrestling alligators, and it’s hard to imagine there was a time when this wasn’t part of the public consciousness.

Annie Edson Taylor did it first. On October 24, 1901, her sixty-third birthday, she plummeted down Niagara Falls in a barrel cementing her legacy in American folklore and becoming the Queen of the Falls.

Many people thought she was a woman beyond her time.

That’s Elsie Edson White, the great grand Niece, of Annie Edson Taylor.

Every time I talk to people I meet, I ask them, well, do you know Annie Edson Taylor. Most of the time people don’t. I have little cards with my information on them about her, my id card that I share with people and then after a minute, what a minute I do know about her but it was so long ago that a lot of people today don’t think about that.

If necessity is the mother of invention, Annie Edson Taylor’s idea for her famous feat

was born out of poverty. While certainly a spectacular feat of courage, it also has a lot to say about gender and class in the Victorian era. With firm ideas about station and social class, and little opportunities for economic independence, risking death seemed to Taylor a reasonable, almost necessary risk.

Taylor was the descendant of New England Puritans (A forefather was a deacon in Salem, Massachusetts, and died just as the witch trials were beginning). Her family’s long history in the region translated into wealth. Her grandfather was an early landowner in Cayuga County, N.Y. and Annie Edson’s father owned a flour mill. As a child, she spent much of her time romping around outside on the farm with her 10 siblings and reading. She was, by her own accounts, a dreamer. “My brain was teeming with romance and my heart was often oppressed with the deepest grief in sympathy with all the people I read about.” she wrote (Whalen pg 3)

When she was 12, her father died in an accident. Her mother died soon after, and at age 14, she was sent to a boarding school. There, she roomed with Jennie Taylor, who would later become her sister-in-law when Annie Edson, at age 18, married 29-year-old medical student and Union Army veteran David Taylor. A short time later, Annie gave birth to a baby who died after a few days. Next, her husband died from the lingering effects of war wounds.

Dates and ages get mixed up in this story, in part because Annie Edson Taylor frequently lied about her age. Her self-aggrandizing autobiography appears to be born of the rich 19th-century tradition of mixing fact and fiction for the sake of sales.

Here’s Elsie Edson White again:

She has been told to be a storyteller. Some of these stories are repeated over and over again, and that doesn’t mean it’s fact. It’s just been repeated and repeated. People out there have a lot of stories and they tend to change them from time to time. And I’m a factual person.

However, what is clear is that within a few years, Taylor lost both her parents, her husband, and her child, and was suddenly on her own. She later wrote, “I realized the imperfections of my education and the folly of a too-early marriage.”

The death of 620,000 men in the Civil War meant that widowhood was not uncommon at the time. Still, economic prospects for unmarried women weren’t great. Often, widows joined the household of a child or sibling. Remarrying was another route to financial security. Some took on work as seamstresses or washerwomen. Taylor, having ideas of her high birth, would not take on work she felt beneath her. She once wrote.

“For the woman who has had money and handled considerable money all her life, for I was born well connected, it is horrible to be poor.” She added that after her husband died, “I couldn’t get anything to do in the big cities unless I went scrubbing and that I would not do.”

Teaching was one profession open to educated women of the time, so Taylor borrowed money from a family friend against her life insurance to continue her schooling and become a teacher. Upon attaining the qualifications, Taylor then traveled west with friends Kate and William Kingsbury.

In her autobiography, Taylor includes a couple of wild stories from this time that reek of pulp embellishment. It’s possible they’re true, but they’re hard to take at face value. The first is that while looking after the Kingsbury’s property, she was attacked by thieves who chloroformed her and searched her room for the rent money she’d taken in. The second story is that while traveling, her stagecoach was again held up by robbers who took thousands from her traveling companions but to whom Annie refused to hand over the $800 she hid in her dress. “I’ll blow out your brains.” the thief reportedly told Annie, to which she replied, “Blow away. I would as soon be without brains as without money.”

While chloroform was becoming widely used in the wake of the Civil War, it was more commonly used in medical procedures or as a plot device in mystery dime novels than in home invasions.

Nonetheless, Annie left Texas and the Kingsburys, and went to New York where she became a dance student, and eventually, an instructor. She then took her talents to Tennessee and began teaching dance there, then Asheville, North Carolina where she boarded with a “cultivated Southern family.” She kept moving, working. Alabama, back to Owasco, New York, back to Texas, Mexico, San Francisco, then, while on a train back to New York, was present for a train robbery.

In Chattanooga, a bad investment and a fire took most of her savings. Next, Charleston, South Carolina, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Indianapolis, San Antonio, Austin, Syracuse, and several other places. She traveled on a friend’s money to Paris, before settling in Bay City Michigan where she reports having one hundred pupils. Still, she could not get ahead financially, spending about as much to retain clients and advertise as she was taking in.

Again, she traveled back to Texas, then to Mexico with a friend where, according to Taylor, she ended up in the company of a former First Lady of Mexico on a private railway car provided by President Diaz to Mexico City. Next, San Antonio, St. Louis, Chicago, and back to Bay City Michigan.

Taylor’s city hopping is sometimes explained by her adventurous spirit and her constant search for viable employment. Clearly, too, she relied on the charity of friends and family, and perhaps this was a reason to move from place to place. Also, later in her life, there are examples of her leaving cities with bills owed, and I wonder if sometimes this was a reason to skip town.

It was in her room in Bay City, that upon reading in the newspaper about the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, that Taylor says, “…the thought came to me like a flash of light – Go over Niagara Falls in a barrel. No one has ever accomplished this feat.”

Taylor repeated this “flash of light” story often, but while her conception of the barrel stunt was no doubt novel and ambitious, great art is always derivative of other art. Carlisle D. Graham was the first to convert a barrel into a nautical vessel on the Niagara River. He traversed the rapids of the Niagara Gorge, about 2 miles upriver from the Falls, in a barrel in 1886. He repeated this trick several more times and helped others repeat it as well. In 1889, Graham sent his barrel over the falls and claimed to have been in it. He had not been, and while he made a bit of money showing off his miraculous barrel, he was found out. Meredith Stanley claimed to have gone over the falls in a barrel in 1893, though her boast was widely dismissed. In 1901, when Graham attempted a dual barrel run of the rapids, him in one barrel, Maude Willard and her dog in another. Willard’s barrel got stuck in a whirlpool she suffocated and died inside. Graham and the dog survived. This happened in September, just a few weeks before Annie Edson Taylor’s feat.

So, the idea of going over Niagara Falls in a barrel had been flirted with plenty. It was likely desperation more than inspiration that hit Taylor like a flash of light.

By 1901, Taylor had already surpassed the average lifespan of a woman at that time by more than a decade. At the time, social safety nets were all but nonexistent, and jobs for women were scarce. It’s also possible that as she aged, she became a less-desirable dance instructor compared to her younger competitors. She wrote: “When I was younger and a good deal better looking than I am now, I could make money easier. People are more willing to help a young woman than they are to help a woman in middle life. They don’t seem to be the least bit attractive.”

With this stunt, Taylor planned to put an end to her money troubles one way or another. “It would be fame and fortune or instant death,” said Taylor, and she began making sketches and prototypes out of cardboard. The West Bay City Cooperage company created Taylor’s custom 160 lb, 4 ft high barrel. She added leather straps to keep her body from jostling inside the barrel, cushions, an opening where air could be pumped in by a bicycle pump, and an anvil ballast weighing about as much as the barrel itself. Estimates put the cost of the barrel at $50, more than $1,500 today.

Next, she needed a manager, and first, she went to family, Elsie Edson White’s grandfather.

She actually asked him to be her manager, but he thought it was an unsafe activity and he would have nothing to do with it. Also, I am assuming he was too busy with his own life in the early 1900s to quit what he was doing. He had not started his family yet. My father was his first child and my dad was born in 1907, so it was seven years before he had his family, but still, he had his family, and change jobs, and you have an aunt who wants to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel, I mean my goodness. What would you say?

Instead, she secured Frank “Tussie” Russell as an advance man and publicist. Russell’s resume included transforming a group of locals who had been jumping from lumber piles in the Saginaw River into an act audiences would pay to see.

From the beginning, Taylor and Russell had different ideas about how to make money from Taylor’s spectacular feat. While Russell saw dollar signs in Vaudeville Acts and dime museums, Taylor found such establishments distasteful. Eventually, she came to realize, “After I got a manager, I learned that I could make nothing of the venture without notoriety.”

Taylor and Russell quietly tried raising money for expenses in advance. Taylor tried to secure loans from personal acquaintances who were abhorred when they learned of the feat she proposed. A local Bay City company at first agreed to put an ad on the side of Taylor’s barrel but later backed out, maybe fearing they’d end up with an ad on the side of her floating coffin.

Then, In September of 1901, Russell told the Bay City Times-Press he had a client, yet to be named, who planned to go over Niagara Falls in a barrel. After milking that news for what he could, he revealed Taylor’s name a few weeks later and displayed the custom barrel in downtown Bay City.

Russell and his wife went to Niagara Falls to do advance work leaving Taylor in Bay City where she continued to give interviews describing her dire circumstances, the intricacies of her barrel design, and claiming that in anticipation of being trapped in an eddy, she would bring along with her some sherry and biscuits.

Rumors swirled that Chief of Police William Dinan would hold Russell accountable for murder if Taylor should die. Taylor drafted a letter with the intention of absolving Russell of guilt in the event of her death.

“The idea originated in my own brain, and so far as has been carried out by me alone. The barrel was made to my order after a diagram drawn by myself.” Then, she added a sentence about Mr. Russell’s character she likely came to regret: “I believe him to be thoroughly conscientious and honest in every way.”

Russell arranged for Taylor’s barrel to be displayed at a local Niagara hotel to drum up excitement. Next, he hired Fred Truesdale, local Niagara hunter and ruffian to help them find the best route down the falls. Russell had done this for other stunters as well and had several times sent barrels down the river to study the results, sometimes with feline or canine passengers. It was likely Truesdale who was responsible for putting a cat in Annie’s barrel for its trial run on October 18. Later, this cat, Iagara, (Like Niagara with no “N”) or another feline stand-in, became a celebrity as well.

If Taylor was uncomfortable with Russell’s low-brow bonafides, she must have found Truesdale abhorrent. Years earlier, he’d been charged with discharging firearms in a public place. Weeks before being hired by Russell and Taylor, the Lockport Journal reported, “The Truesdales of Niagara Falls are in Trouble again. Anna Truesdale swore out Monday a warrant for the arrest of Charles Truesdale, on the charge of using bad language and abusing her. The arrest led to further complications and Fred Truesdale and his wife mixed in. There was a general discussion of the affair, during which Charles claims Fred assaulted him. Officer Eagan arrested the whole four, Charles and wife and Fred and wife.”

Leading up to the final plunge, there were several false starts to the stunt by Taylor and her crew, reasons given ranging from weather, a death in Taylor’s family, to a photographer not having promised promotion photos ready to sell, to evading the police.

The October 21 th 1901 Lockport News ran the following article: “MRS. TAYLOR IS ALIVE YET. Dancing Teacher did not Try to go Over the Falls Sunday Afternoon.

Mrs. Annie Edson Taylor did not go over Niagara Falls: on Sunday and is consequently very much alive yet. She has now fixed the date for the suicide trip for Wednesday Afternoon, or her manager has done so. The reason why she did not go over on Sunday? Oh, Just because. That has been reason enough for three or four previous postponements. There are a few other reasons, but they don’t count much.

Possibly one reason is that no one showed sufficient anxiety and activity in trying to put a stop to the trip on Sunday. If they would first step up and arrest Mrs. Taylor and her manager and take away the barrel she would get almost as good advertising without the sure death attachment which the trip is burdened with.

After much build-up, trial runs, and false starts, Annie Edson Taylor was ready to enter her barrel on the afternoon of October 23rd. She asked onlooking reporters to turn their heads as she wriggled in knowing it, “would not be a very graceful act.” “You cannot see me get into the barrel,” she said, “but I will let you see me after I get into the barrel.”

The barrel lay on its side, and Annie got into it by crawling backward on her hands and knees. Next, Annie secured herself into the leather straps and other helpers gave her cushions to stuff around her body and her flask of sherry. In her right hand, she held a tube that ran to the outside of the barrel to help her breathe.

Truesdale, Rufus Robinson, and others lifted the barrel using long crowbars and in that way, were able to lift it “like Pall Bearers” wrote author Dick Whalen, and load it into the boat. A photographer snapped a picture which survives to this day of the barrel in the boat, a small opening in the top with Annie’s head, resting on a white pillow, visible.

The combination of wind and rough water made the river hard to navigate. Truesdale and Robinson feared going over the falls themselves if they continued on, and the effort proved to be another false start.

The next day, Annie Taylor’s team underwent similar preparations, but instead of loading Taylor into the barrel at Trusedale’s property, they left quickly, earlier than promised, with Annie a boat passenger to be loaded in the barrel later. With Rumors of a police raid about, Robinson, who had helped navigate the boat previously, grew skittish and was replaced at the last minute with Billy Holleran.

In the crowd of approximately 200 on the riverbank was daredevil Petter Nissen who traversed the Niagara rapids in his boat “Foolkiller.” Three years later, he’d die while trying while crossing Lake Michigan in Fool Killer 3.

Robinson did end up following in another boat with a photographer. They stopped and took pictures of Annie as she got into her barrel at a shallow spot near Grass Island.

A crowd of thousands stood by ready near the falls, though by some reports, fewer than had been there the day before, fatigue quelling the public’s excitement for the spectacle. The Maid of the Mist boat, with passengers on board, waited below.

This part of the story is often told with lots of grandiose language and speculation, with lots of descriptions of the power of the falls, facts, and figures, and truly, one can only imagine what this experience would be like.

I think it’s best to go with Annie Taylor’s account, not the composed narrative she’d later put in her memoir, but from an interview she gave the day after her feat, a day she would later say she talked too long and too recklessly to reporters.

“I told the men to turn their backs on me, which they did, and I backed into the barrel. Then I put a strap around me and strapped it up to the foot of the barrel. I fixed my cushion at the front and back of my body. I laid in a reclining position with a pillow under my headband with my arms in the straps. I did not have straps in my hands. I had a rubber tube in the barrel put in by a little screw from the inside, and the men attached a bicycle pump and pumped the barrel just as full as it could be. It made me breathe heavy. But when I opened the little tube over my head, – I wanted to try it before I was set loose – water came in. I drank the water. Then, I told Mr. Truesdale, the boatman, that when he cut me loose, to rap on the barrel with his oar. I said to Mr. Truesdale, when he rapped on the barrel, – and I had to holler – there is water coming in here. He answered, “There isn’t enough to do any harm, and you will be over in five minutes.”

Then, I thought my heart would burst, when I knew it was set loose, and I was floating toward the Falls. I could hear the roar as I drew nearer. Then, my heart beat so I thought at first it would suffocate me, but still if I had wanted to back out, I couldn’t. No mortal power could get me out of that, and I didn’t want to be taken out. When it went over the first drop, about 15 feet high, I struck on the rocks and the barrel rolled round and round. Then, I went around what seemed to be a curve, and I rolled over and struck on a rock, and it seemed to me I could feel myself when I hung on the edge of the precipice. I knew exactly where I was. I knew I was on the edge of the precipice and I braced myself for the shook, and for about three seconds, I lost my reason. I didn’t faint. The next thing I knew, I was in the cataract below. I think the velocity of going over took my senses away. I realized that I was in the cataract under the Falls, and the only sensation that I could think of was as if you put a dasher in a churn and churned with all your might and push it around and round at the same time, over this way, round and round, and over this way, and thrust it up and down at the same time. It was a tremendous churn. Every time it came round the barrel was standing up. I was on my knees in the bottom of the barrel, for the water was up to my waist. And every time it went up, tossed up in the water, it seemed to me, it tossed out of the water, almost. I could feel it come down, and every time it came down, it struck on a rock. It would stand on the rock and grind and grind. Water was coming in…from the top, and my hands were in it while my arms were in the loops. My head would knock on the front of the barrel and then on the back and I expected to be killed, although I realized all the time where I was and was not sorry that I was doing it. Then, all to once, it gave a jump and it seemed to me it went like a streak of lightning. It must have shot 15-20 feet out and I went into an eddy or a pool where I went round, just like that. The barrel nearly stood up, and that is the place where things go down and disappear forever, and I realized where I was. I waited for somebody to get me out quick. Then, I felt the barrel being dragged to the shore.”

This is the feat that is now forever linked with the spectacle of the falls itself, whether or not Annie Edson Taylor’s name is attached to it. It’s also just the beginning of her quest to replace nomadic poverty with fame and fortune. What happens next is a journey of its own, and we’ll get into that, in part 2.

Thank you for listening to The Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. If you’re enjoying the show, please write a review and tell a friend. Also, please consider connecting on social media. On Twitter and Instagram, I’m theodorecarter2. I’m also on Facebook as well, and there, you can join the public group “Niagara Falls Daredevils” to share your own stories and engage in discussions with others. This show is just me. There’s no funding behind it or other people behind the scenes. So, I’d love to hear from you to know more about what you enjoy, what you think I got wrong, or which daredevil I should research next.

The music you’re hearing now is from Holizna, slightly altered in parts for use in this podcast.

The song “Bindweed,” by Axltree, plays in the background of this podcast.