Listen here. Full transcript:

This is Yuniko Harada, and this is “The Blondin March” composed by Albert Poppinberg:

Blondin March Plays

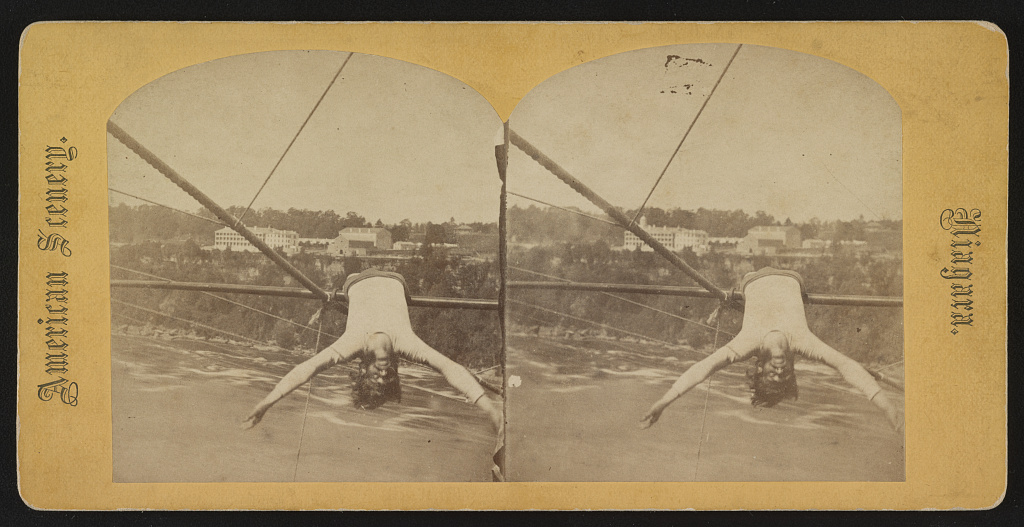

The betting odds had been stacked against him, and thousands of onlookers had held their breath wondering when, not if, Charles Blondin would lose his balance on his tightrope and fall 160 feet into the swirling waters of the Niagara Gorge, wondering if the bands on hand, both in Canada and in the United States, would need to shift their joyous carnival-like music to a slow sad dirge. But Blondin, not only survived his perilous journey but appeared at ease out on the rope, laying on his back for spectacle and hauling up a bottle of wine with a string from the Maid of the Mist tourist boat below. His great walk across the tightrope sent the gathered crowd into revelry and the next day, newspapers and witnesses carried his story outward and Charles Blondin became the Hero of Niagara.

For Blondin, this was only the beginning. The crowd, though amazed, had only seen a smidgen of his talent. He’d been perfecting tricks for the tightrope all over Europe and the Americas since boyhood, and he knew that he could perform them above Niagara Gorge just as he had elsewhere. This also had to be just the beginning because, after all of the extensive work and expense he’d taken to string up his tightrope and drum up a frenzy among the populace, he hadn’t made much money. And while the rope was up, while his name was on the tip of everyone’s tongue, he would walk across the gorge again.

Welcome to the Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. In this podcast, we’ll examine the bravery, stupidity, hubris, and eccentricity of people who have attempted daring feats at Niagara Falls. My name is Theodore Carter. I’m an author whose novel research went too far, and I got swept up in the current of stranger-than-fiction stories surrounding Niagara Falls. Now, I’m putting that research into this podcast.

Shortly after his first walk, Blondin announced a second scheduled for the fourth of July, and he proclaimed that this time, he’d make the crossing while tied into a sack. Additional seating was added and tickets sold in hopes of boosting revenue. In some spots, this seating blocked formerly free viewing points. The previous walk produced a lot of newspaper copy both local and far-flung, and as a result, opportunists rushed in to make a buck, creating a carnival-like atmosphere exceeding that of days before. Blondin hoped this time to cater to to the “carriage trade,” this is 19th century speak for rich people with money to burn. This meant better seating and proximity to bathrooms.

Hucksters set up stands to sell locks of Blondin’s Blonde hair. Biographer Ken Wilson wrote, ‘Had all the locks of blonde hair come from Blondin’s head, he would have been completely bald.” Bits of “the actual rope” were for sale too despite the fact that everyone could clearly see the rope in place over the gorge. No doubt the whiskey was flowing and the pickpockets were back out looking for easy marks.

During his July 4th show, Blondin set off on the rope while walking backwards. However, he only made it a short way out before he returned to his starting point on the American side and asked that adjustments be made to the guy ropes. Then, he set off again. He did his trick of laying down. At one point, his balancing pole became entangled with a guy rope providing a moment of drama. It’s hard to be certain if the difficulty with the slack in the rope and his entangled pole were real obstacles or manufactured complications designed to elevate his show.

Nevertheless, Blondin made it safely to Canada again. There, he put on a specially made sack, because while many backers in America thought the sack idea too dangerous, he had not received such protests from the Canadians. Now covered, aside from his legs and his arms, with which he held his pole, he set off toward the U.S. His legs shook, and again, whether that was out of legitimate distress or showmanship is unclear.

He made the journey successfully and met success as an acrobat and an artist. This walk had been even more spectacular than his first. However, again he largely failed as a businessman. Despite the build-up, the crowd was about the same size as it had been on his previous effort, and catering to the “carriage trade” had not boosted income significantly.

He scheduled another walk for July 15th. This time, former president Millard Fillmore, at the time a resident of Buffalo, was in attendance. Blondin borrowed a hat from a member of the crowd and always doing his best to outdo his previous performance, he walked the entire length from the United States to Canada backwards. He did, however, stop in the middle of his trip to lay down on this rope again dangling above the Maid of the Mist. Then, Blondin held out the hat, and sharpshooter Captain Travis fired a pistol from the boat below through the hat in Blondin’s outstretched hand. He then lowered the hat by a rope for inspection by the ship passengers.

On the Canadian side, where it’s by now been established they have a stronger stomach for Blondin’s wilder antics, he put on a monkey suit and on his return trip pushed a wheelbarrow. All of this while still carrying his 26-foot-long balancing pole. Newspapers reported he stopped several times to make “monkey grimaces” and to stand on one leg. Again, he reached the US safely to the cheers of the crowd and was carried off in his carriage still in his monkey suit.

While I can’t find a photograph of this costume, there is a wonderfully weird illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, and the 19th-century monkey suit looks every bit as frightening as you might expect a Victorian-era monkey suit to look.

While Blondin was whipping Niagara into a funambulist frenzy, his young wife Charlotte gave birth to their 3rd child in Cincinnati. Blondin left Niagara to be with her for a time. Not long afterward, with his rope still strung across the gorge, he announced one final walk in Niagara on August 17th, and that he would carry a man on his back. This time, he walked the length of the rope with no pole, went to Canada and picked up his manager, Harry Colcord, and carried him back to America. Colcord weighed about as much as Blondin himself. The trip back took 40 minutes, and several times the two took a pause to rest.

With gambling wagers high for each of his walks, there were several incidents of presumed sabotage. A man was found under one of Blondin’s guy ropes with a knife, and on Blondin’s return trip, someone shook his rope. Nonetheless, Blondin continued to cross the gorge unharmed.

Later that same month, Blondin took a small stove out over the gorge and prepared omelets which he then lowered down to passengers on The Maid of the Mist. There were more trips across Niagara Gorge. His 1862 biography claims that he made 300 trips in his in his lifetime, a comical exaggeration that you can still find repeated often. More reliable sources put the number of trips at around 16 over the course of the warm seasons of 1859 and 1860.

Some of the tricks he’s reported to have pulled off while crossing include: carrying a man on his back, walking at night with train lights fixed to the end of each wire, dangling from the rope, walking in shackles, eating cake and champagne, walking amidst firecrackers, and on stilts.

To a large degree, Blondin fell victim to his own success. Like Franz Kafka’s hunger artist, the public lost interest despite his escalating skill and bravado. He made the impossible look easy, and because he never plummeted to his death, the drama fell out of his performances. Also, copycats circled his celebrity. A tightrope walker crossed the falls in Rochester, the site of some early Sam Patch jumps. A rival crossed Niagara Gorge as well.

He never did succeed in converting his artistry into great profits, and, saturating the public’s appetite in Niagara, he moved on to perform elsewhere in The States, or, as his triumphant, over-wrtitten biography put it, “He sought out perilous localities, eligible for his performance, in various parts of the Republic”

Meanwhile, the country was at the beginning of a civil war. New president, Abraham Lincoln, in doing his best to navigate disparate opinions on the direction of his young country, pointed out in himself many similarities with Blondin as he too balanced precariously. Several political cartoonists depicted Lincoln walking a high rope, sometimes with a man on his back or with a wheelbarrow like Blondin’s. Later, with the civil war waging and northerners criticizing President Lincoln for his centrist stances, Lincoln is quoted as saying:

“Do you remember that a few years ago [Charles] Blondin walked across a tightrope stretched over the falls of Niagara?”

Suppose that all the material values in this great country of ours, from the Atlantic to the Pacific — its wealth, its prosperity, its achievements in the present and its hopes for the future — could all have been concentrated and given to Blondin to carry over that awful crossing and that their preservation should have depended upon his ability to somehow get them across to the other side. And suppose that everything you yourself held dearest in the world, the safety of your family, and the security of your home, also depended on his crossing.

“And suppose you had been on the shore when he was going over, as he was carefully feeling his way along and balancing his pole with all his most delicate skill over the thundering cataract. Would you have shouted to him, ‘Blondin, a step to the right! Blondin, a step to the left!’ Or would you have stood there speechless and held your breath and prayed to the Almighty to guide and help him safely through the trial?”

Blondin also grabbed the attention of Mark Twain who when visiting the falls in 1869, couldn’t help but recall the funambulist’s famous feat.

Further along, they show you where that adventurous ass, “Blondin,” crossed the Niagara River, with his wheelbarrow on a tightrope, but the satisfaction of it is marred by the reflection that he did not break his neck.

( Mark Twain, Buffalo Express, August 29, 1869)

Clearly, Blondin had left an indelible mark on American culture, but by 1861, it was time for him to leave. This time, instead of traversing Niagara Gorge, Blondin crossed the raging current of the Atlantic Ocean for Europe.

After capturing the attention of the American public and the United States president, The Hero of Niagara ascended to the status of a folk hero. However, with audience interest waning and Civil War underway in the United States, Blondin made his way back to Europe, securing a run of shows at London’s Crystal Palace and continuing to do his best to keep his audience in awe. Omelet cooking remained a steady trick, as did the wheelbarrow, sometimes with a passenger, and once, with harrowing results, filled with fireworks. He drew nearly 1.5 million spectators during the show’s run.

When that engagement ran its course, he traveled to new performance spaces including the Sheffield botanical gardens where crowd estimates were between 35-8000 thousand. In Birmingham, he incited a riot reminiscent of Woodstock ‘99. The report from the Belfast Morning News reads:

“…there was a tremendous crush outside the entrance, which the staff of policemen were utterly unable to quell. A mob of ” roughs” attempted force passage through the turnstiles at the gates just as it was growing dark, and being repulsed by the police, who were mounted, they broke down the railings and fences and set fire to them, and, arming themselves with stones and bludgeons, commenced a violent attack upon the police. Several of the constables were severely wounded on their heads and faces by the contact of sharp stones, and a valuable horse ridden by a policeman had its leg broken and was obliged to be shot. Finding hit force utterly incompetent to suppress the riot, Inspector Wilson, the officer in charge, despatched a messenger into the town for reinforcements, and Superintendent Legget, in the absence of the chief, sent down by omnibus and train a large number of hastily-collected policemen to the scene of the riot.

At the Liverpool zoological gardens, Blondin found a new way to amaze his audience when he wheeled a lion across a rope in his wheelbarrow. Here his fantastical biography digresses into some questionable anecdotes. One is that in in Birmingham, Hot air balloonist Henry Coxwell watched Blondin’s performance from the air and wrote:

In a park where stately trees assumed the diminutive form of gooseberry bushes, and large sheets of water looked like little ponds, and Aston Hall resembled a tiny ecclesiastical model, there was congregated on the right-hand elope of the Lilliputian ground an immense swarm of busy bees, A spider’s web betwixt two sprigs was spun near them, and a gnat-fly perched on one thread caused the bees to buzz, and move their heads as if prodigiously pleased. The gnat, in moving along, appeared to have the leg of a spider across him, and several times he turned over, which provoked the bees to buzz in good earnest and the humming sound rose higher and higher.”

During a second run at The Crystal Palace, Blondin wheeled his 5 yo daughter across the rope in a wheelbarrow while she threw rose petals to the crowd below. This spectacle proved too much for British audiences who enjoyed watching him put himself at risk but were disgusted by seeing his daughter out on the rope. Complaints went to authorities and Blondin agreed never to put his daughter in peril again,

However, as Charles Dickens wrote, “Half of London is here eager for some dreadful accident.” and putting a child at the center of this threat of catastrophe proved too much.

Blondin’s chasing of his own spectacle became comic in a way that is best highlighted by a typo in one of his advertisements. While this incident can be verified with more reputable sources, it’s most colorfully recorded in his 1862 biography, which reads:

“He was engaged to perform at a fashionable watering-place in the West of England and amongst other great feats which were expected of him, it was announced that he would appear on the rope with an” Elephant’s Cooking-apparatus,” and partake of luncheon of his own preparing.” The unfortunate line in the placards which gave rise to such extraordinary expectations on the part of his audience should have read, an ” Elegant Cooking apparatus;” but although elephants in modern days, whatever they may have been of old, are not proverbial for possessing a knowledge of gastronomy, much less for being equipped with patent cooking- stoves; he was literally expected to perform the feat in question, and a portion of his audience grew clamorous and went away in high dudgeon not to say disgust, when he mounted the rope with an ordinary cooking-stove attached to his back.

Despite sky-high expectations, Blondin continued to awe audiences in his 70s. He incorporated a bicycle into his act during the late 19th-century bike boom. He returned to the United States in and continued to preform.

An excerpt from a New York Tribune article about Blondin at that time reads:

Now when he returns to America after decades and exhibits the even more startling nerve of tripping blithely on the tightrope with sixty-five years on his back, a sparse gathering of Coney Island visitors look with languid interest at the doughy funambulist before the Sea Beach Pavilliallion.

He gave his final performance in 1896, a year before he died from complications from diabetes at the age of 75.

The Hero of Niagara is perhaps most legendary in England where he spent most of his later years in what he called Niagara Villa in the South Ealing area of London. The house isn’t there any longer, but in the neighborhood where it once stood, you can walk down Niagara Avenue or Blondin Avenue to Blondin Park. Blondin is buried five miles away in Kensal Green Cemetary, and there, every year, The Blondin Memorial Trust hosts a toast in honor of the performer’s birthday. Picture and videos of the event show it to be a mix of costumed revelry featuring pink tutus, poetry, and champagne, a celebration as flamboyant as the man himself.

In addition to the physical spaces and rituals that preserve Blondin’s legacy, There are a number of beautiful poems too. They’re songs, marches, both from the 19th century and today. I’m going to close with this one published in Punch during Blondin’s heyday. Elizabeth Carter will perform it for an auditory change of pace. In the background, you’ll here The Blondin March, written in 1861 by Albert Poppenberg and performed by Yuniko Harada.

Of all the sights in England now,

And I’ve looked everywhere,

There is not one, of any sort.

With Blondin can compare;

He is the marvel of his age —

That every one admits —

So, fit it is that he should beat

All others into fits;

The world counts seven wonders up. An eighth I will install.

The Hero of Niagara, And greatest of them all.

Though small in stature, slight in build.

With truth it may be said,

He’s never undersized but when

You see him overhead,

A tripping of his own accord,

Like some fantastic elf

To whom is given rope enough

But not to hang himself.

The world counts seven wonders up, an eighth I will install,

The Hero of Niagara, And Greatest of them all.

When he the foaming rapids crossed,

And first achieved renown,

So rapidly his fame went up

On all hands it went down;

The people clapped, and cried “hurrah!”

With all their soul and strength

To see so short a traveler go

To such an awful length.

The world counts seven wonders up, an eighth I will install,

The Hero of Niagara, And Greatest of them all.

A prodigy of daring is

This gallant little soul –

By birth a Frenchman, but in race

inclining to a Pole:

It makes one’s hair stand all on end,

While every heart-pulse beats,

To see his little legs perform

Their very mighty feats.

The world counts seven wonders up, an eighth I will install,

The Hero of Niagara, And Greatest of them all.

We frequently hear sailors boast

The years they’ve crossed the brine,

But who with Blondin can aver,

As oft he’s crossed the line;

And crossed it, too, in storm and calm,

When winds blew hard or soft,

So that whatever weather fell,

He still was up aloft

The world counts seven wonders up, an eighth I will install,

The Hero of Niagara, And Greatest of them all.

His culinary powers are put

To an eccentric use,

Because though omelets he’ll cook,

He won’t cook his own goose;

And, then, he’s ne’er in liquor, save

When’ he’s in sack, or lunch

Is followed or preceded by

A barrow full of punch

The world counts seven wonders up, an eighth I will install,

The Hero of Niagara, And Greatest of them all.

Of Blondin, more I fain would sing,

But, ten to one you’d say –

Those base notes drop, and leave him to

The tenor of his way.

When next a cataract he dares,

May I be there to see

Both what he does, and how he fares,

But no catastrophe.

The world counts seven wonders up, an eighth I will install,

The Hero of Niagara, And Greatest of them all.

Thank you for listening to The Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. If you’re enjoying the show, please write a review and tell a friend. Also, please consider connecting on social media. On Twitter and Instagram, I’m theodorecarter2. I’m also on Facebook as well, and there, you can join the public group “Niagara Falls Daredevils” to share your own stories and engage in discussions with others. This show is just me. There’s no funding behind it or other people behind the scenes. So, I’d love to hear from you to know more about what you enjoy, what you think I got wrong, or which daredevil I should research next.

The music you’re hearing now is from Holizna, slightly altered in parts for use in this podcast. Thank again to Yuniko Harada. As far as I know, this is the only version of The Blondin March that exists on the Internet.