Listen here. Full transcript:

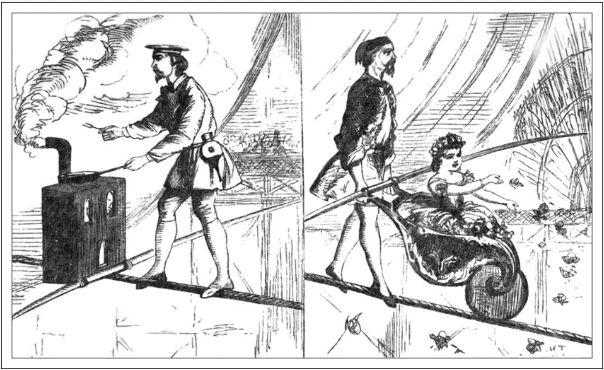

It’s 1862 in Sheffield, England, a city of less than 200,000 people and you are one of thousands, maybe as many as 80 thousand people, assembled underneath a man walking on a tightrope high in the air stopping to lie down on his back, to turn a summersaults, and once cover his eyes with a blindfold. The whole time you are terrified he might fall, but also, this danger is the very reason you and everyone else has come to see him.

You are witness to a once-in-a-lifetime talent, a man so skilled his name has become synonymous with the feat he performs. Now, a tightrope walker is a Blondin, as in “have you seen the new Blondin? Have you seen the female Blondin? The American Blondin? I heard there’s a new rope walker better than Blondin.

You are watching the real deal, the one and only Charles Blondin, a Frenchman, but one who gained notoriety in America, a place where lurid acts like this flourish. But his act grew to something elevated, something grand and beautiful he could take back to Europe, that he could bring from city to city. You are watching The Hero of Niagara, the man who dared to cross back and forth over the gorge sixteen times, sometimes pushing a man in a wheelbarrow, sometimes hoisting a man on his back, and sometimes stopping to cook an omelet. And right now, No one draws a crowd, commands, and holds a crowd, like Charles Blondin.

PODCAST INTRO:

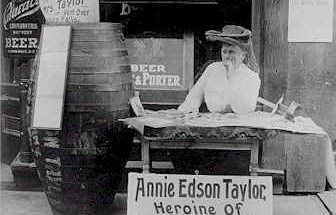

Welcome to the Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. In this podcast, we’ll examine the bravery, stupidity, hubris, and eccentricity of people who have attempted daring feats at Niagara Falls. My name is Theodore Carter. I’m an author whose novel research went too far, and I got swept up in the current of stranger-than-fiction stories surrounding Niagara Falls. Now, I’m putting that research into this podcast.

1862 Biography Blondin: His Life and Performances describes how a young Charles Blodin was inspired by a troupe of traveling performers as a young boy. Then, he learned to walk a tightrope, wowing instructors at a local gymnastics school who helped him hone his skill. Orphaned by age 9, Blondin worked hard to improve before sailing off to make a name for himself in America.

None of this is true. This often-cited biography is largely fictionalized, an interaction between fact and myth at a time when the showman P.T. Barnum was demonstrating how to exploit the growing number of American newspapers and expanding printing technologies. The problem is, the book’s contents have been repeated in most of the subsequent books and articles about Blondin for 160 years. Figuring out Blondin fact from fiction can make your head spin. Luckily, I found some who already had.

Bowman: My name is Donna Janell Bowman I’m a children’s book author and writer and speaker and writing coach in Central Texas.

I found Bowman from her blog post where she is pictured in the depths of the Niagara Falls Public Library.

Bowman: I thought I hit paydirt when I discovered the 1862 biography written by George Banks about the great Blondin supposedly with London’s collaboration. Now if Blondin was part of writing this book and was there and he vetted it, it generally makes it a primary source and that’s a gold mine. Everything written about blondin since then that 1862 biography

Years earlier, when I started researching this story, I had sort of put feelers out looking for any descendants of the Great Blondin and Miracle of Miracles, I connected with one of his great-great-grandsons in France who was thrilled to hear about my book. He speaks fluent English. He’s his family’s historian, so he’d already done a truckload of research into his ancestor, Blondin. So, so anyway with his help we really solve the mystery and he was able to dispel the myths that 1862 biography because he knew his family’s history.

The real story begins in the way Donna Janell Bowman’s children’s book, King of the Tightrope does, with Charles Blondin, who’s real name was Jean François Gravelet born in 1824 into a family of acrobats and “rope-dancers.” Blondin’s grandfather, father, Andre, and uncle performed together until Andre’ was conscripted into Napoleon’s army. He served for five years and earned the cross of the Legion of Honour. Upon returning to civilian life, Andre married acrobat Eulalie Merlet. Together, they had four children and as soon as these children could walk on a rope, they began performing and traveling all over France and in other neighboring countries.

Andre died when Jean François was 13, but the troupe carried on and later added Marie Rosalie Blancheri when she married Jean Francois nine years later.

At the age of twenty-seven, he joined the Ravel family, the well-known French troupe of equestrian and acrobatic performers. Several years later, he followed the troupe to the United States. Leaving his wife and family in France.

This is where his 1862 biography launches into an aside too rich to exclude:

“During the raging of a violent storm, a young man of noble birth, who chanced to be a passenger on board the same ship with him, was suddenly precipitated overboard, as the ship rose and sunk in the black abyss of waves that yawned around her, Blondin, with a bound, sudden as that-of the panther, leaped after him; the winds shrieked and howled like demons let loose, and the hissing surging wares swept mercilessly over them; but the “strong swimmer,” the future Hero of Niagara, breasted them notwithstanding, and courageously approached the drowning man in time to save him. Struggling gallantly against desperate odds, he reached the ship and was drawn up in safety, but not before he had securely lashed his fainting companion in the rope that was thrown out to him. Deeds like these go far to prove that BIondin’s is no artificial courage.”

The biography continues to say state that Blondin..”was more like a fantastic sprite than a human being. People looked on, and disbelieved their own eyes. Had he lived a century or two earlier he would have been treated as one possessed of a devil; for no decrepit old woman in a red cloak, suspected of being a witch — no mysterious investigator of the physical sciences — no alchemist or astrologer, ever had more terrible charges of witchcraft or evil agency alleged against them, than might have been fairly laid at his door.”

Donna Janell Bowman checked the passenger list and weather records for the journey. There wasn’t a nobleman or a storm. The same biography claims the Ravel family came to America under contract with P.T. Barnum which also seems dubious. Barnum never mentioned the Ravel’s or Blondin in his autobiography. An 1851 Advertisement in the October 13 New York Harold advertises the Ravel Troupe as a competing attraction to Barnum’s American Museum. The Ravel ad promises

“Gabriel Ravel will cause the disappearance of any young lady present. Tightrope by Francois mons. Blondin”

Aside from helping Blodnin grow in skill and renown, The Ravel’s also gave Blondin develop his stage name which, aside from highlighting his striking blonde locks, helped distinguish him from other performers in the troupe who also had names beginning with J.

While performing in New York where he met a 15-year-old singer, Charlotte Lawrence. While Charlotte’s young age and 12-year age gap with Blondin is alarming, it did not inspire comment in historical accounts. At the time, the age of consent in New York State was just ten.

Blondin was still legally married to Marie Rosalie Blancheri whom he’d left behind with his three children in France. Nonetheless, he found a preacher to bless their union.

For seven years Blondin traveled with the Ravel troupe through North America including California, shortly after it became a state and Nicaragua. However, Blondin had ambitions of striking out on his own, and in the winter of 1858, he came to Niagara Falls and in his mind’s eye, he saw the fantastic expanse between the United States and Canada as a picturesque opportunity. He could cross that distance on a tightrope.

While Blodnin knew he could accomplish the feat athletically, the logistical and business side of the endeavor presented numerous obstacles. First, simply finding amenable landowners across from one another on both the American and Canadian side of the river proved difficult. His original ambition of crossing right next to Horseshoe Falls had to be compromised, and he settled for a route nearly a mile away. This was a disappointment to Blondin, but advertisements had already been printed, train tickets sold, and he needed to move forward.

There were also costs to consider. Just in being in Niagara, Blondin had been incurring costs. His 2,600-foot-long rope alone would cost $1,300, about the equivalent of $43,000 today, plus transport and rigging which was a whole nother set of problems.

The public nature of the event would make it difficult to collect admission, though Blondin did negotiate shares of ticket prices for some select viewing points. He received financial support from several local businessmen who saw potential for profit. Partners included the railroad company who knew they’d transport a crowd, and the Maid of the Mist company, formerly a ferry service that was trying to convert to a tourist service after the suspension bridge built just a few years earlier, threatened their viability. Also, the Niagara Falls Daily Gazette, a fledging paper, saw Blondin as a way to drive circulation and played an important role in the build-up and coverage of the event.

In thinking about Blondin’s preparations and attempts to raise money, it’s important to remember that while no one in Niagara Falls doubted Blondin would create a spectacle, most also thought would die. Any profits to be made had to be balanced against the cost of being accused of feeding the funambulist’s delusions of grandeur and contributing to the performer’s plummet.

Still, while many refused to support Blondin, and just as many dismissed him as mad, no one succeeded in dampening his resolve. With the rope purchased and manufactured, next, Blondin had to figure out a way to string the enormously long, heavy rope across the gorge. A 1-inch thick length of rope was carried by rowboat across the Niagara river and trailed behind the rowers in the water.

Bowman: “There was a rowboat used, and it makes sense that had to start with that thin line by tying it to a tree on the American side, starting upstream because the current was fierce. In 1859 there was twice as much water flowing over the falls as there is today a million and a half gallons of water we manipulated The Falls River so much it’s hard to it’s impossible to look at it and think we’re seeing what Blondin saw the Rope broke several times as the men were trying cross across while being swept down when they finally made it to their side there is a windlass setup on the Canadian side. We will never know what that wind looked like it could have been off of a ship because that was a very common mechanism and sailing ships or they could have just rigged it with the same technology and air quotes.”

Once spanning the length, the rope was then hoisted up with a pulley system, then pulled slowly across, the 1-inch guide rope transitioning to the real 3 ¼ inch rope. The weight of the thicker rope made the task difficult, and several times the guide rope snapped. It took several days to get the rope in place. Then there were more preparations as Blondin secured the guy ropes himself. In the end, the rope was secured about 160 feet above the river with a 60-foot dip in the middle.

Bowman: “Here’s a man in 1859, before the was electricity in Niagara, before there was technology options the tighten a rope and it was a rope, not a wire like today. Rope Walkers generally use a wire and they’re controlled by computer technology. He didn’t have that. Everything was by hand, and it was complete artistry plus so much engineering involved in this process.

June 30th, 1859 was set as the day of Blondin’s much-anticipated walk across the gorge.

The Gazette and interested businesses helped drum up excitement and somewhere between 5-10,000 people assembled on both the Canadian and American side of Niagara Gorge at a time when the population of Niagara Falls New York was just 6,000. Much like the crowds drawn by Sam Patch, the first American daredevil, thirty years earlier, the assembled masses bought food and whiskey from vendors and had placed bets on the likelihood of the performer’s death. Police records show pickpockets ran through the crowds making their livings as well. One notable difference this time is that rail lines had brought some spectators in addition to horses and boats. Also, and this was evident in Sam Patch’s day as well, there was a definite class divide when it came to who went in for this type of spectacle and who did not. This kind of coaxing of death struck many as lurid and low-brow, and certainly, this was reflected in the crowd gathered.

Blondin cut through the crowd in a carriage decorated with the flags of France, Canada, the United States, and Great Britain, Canada being a British territory at the time. A sign on the carriage read “The Great Blondin.” He got out wearing a bright, purple vest, white pantaloons, a curled wig, bright-colored cap, and pointed-toe sandals covering his buckskin slippers. He waved to the crowd, and a cannon fired to announce to the populous strewn about in saloons and taverns, that Blondin was about to begin his walk across the gorge.

He was about average height for a Frenchman of the time, Standing at 5’ 5”, slightly smaller than the average civil war soldier, but at 140lbs he had the thick, muscled frame of a gymnast.

In his heavily accented English, he offered to carry anyone on his back who might want to come along. No one took him up on his offer. He waved to the crowd and motioned to the band set up for the occasion, and they played what was described as “an inspiring strain. ” Based on my research, I’m fairly certain this song was “Jordan is a Hard Road to Travel,” first written for a 1853 minstrel show, but adapted many times, once as Civil War song “Richmond is a hard road to travel” and even as a Peter Paul and Mary song entitled “Old Coat” You can hear it now thanks to The Hardtacks.

Song plays

Then, the fanfare subsided and it was time for the much-anticipated walk onto the rope. In keeping with the carnival atmosphere, Blondin strutted, more than walked out onto the rope and the audience held its collective breath creating an unnerving quiet despite the large crowd. He walked out onto the rope carrying a 26ft long balancing pole. He wore tights and a skirt covering along with a loose ornate, loose collar. And while descriptions of his clothes vary slightly, likely due to a conflation of his many performances, my favorite description has him in pink sequence. Whatever he had on, you can bet it was bright and flamboyant. Certainly, his swept-back blonde hair and curled mustache and goatee, must have looked exquisite

A ways out onto the line, he lay down on his back, and it took the audience a moment to realize this was for show and not a sign of distress. Then, he continued on to the crowd’s relief. Then About midway across the gorge, he lowered a rope to an anchored Maid of the Mist boat below, hauled up a bottle of wine, and took a swig. It wasn’t real wine, of course, being as Blondin was in the midst of a death-defying endeavor that required his full faculties. Also, Blondin was a lifelong teetotaler and didn’t drink even in the most relaxed of circumstances.

Approximately 17 minutes after leaving the United States, Blondin Canada safely, to cheers and rousing music from another band. This one played “Out of the Wilderness.” You know the tune of this song when it’s paired with the lyrics “The old gray mare she ain’t what she used to be.” They also played “Hail Columbia,” the unofficial anthem of the United States.

In Canada, Blondin took a brief rest, and the crowd rested a spell too, but then he made his way back toward America, this time with few flourishes. He made it across in seven minutes and stepped on American soil to the tune of Yankee Doodle. The much relieved crowd could, finally able to burst into jubilation. They cheered and hoisted Blondin and their shoulders and carried him to his carriage, celebrating the accomplishment as well as their own relief, a kind of euphoria that erupts when the threat of terror has been removed. He’d done what many thought impossible, seemingly with ease.

The naysayers had to now admit that Blondin wasn’t crazy after all, but in reality, skilled like no else, a great artist, a daredevil, and maybe even somewhat of the devilish sprite as he would later be described in his biography.

After months of work and at the risk of death, he’d finally achieved what many thought impossible. The problem was, he hadn’t made much money. The very next day, The Lockport Daily Journal and Courier, while reporting Blondin’s spectacular achievement also noted the extensive labor and cost that went into it and predicted several more performances so that Blondin could attain a payout commensurate with his costs. Many more performances were yet to come. They were right, and Blondin announced a second walk on the Fourth of July. More on that, in part 2.

Thank you for listening to The Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. If you’re enjoying the show, please write a review and tell a friend. Also, please consider connecting on social media. On Twitter and Instagram, I’m theodorecarter2. I’m also on Facebook as well, and there, you can join the public group “Niagara Falls Daredevils” to share your own stories and engage in discussions with others. This show is just me. There’s no funding behind it or other people behind the scenes. So, I’d love to hear from you to know more about what you enjoy, what you think I got wrong, or which daredevil I should research next.

Thank you to Donna Janell Bowman. Again, her book is called King of the Tightrope: When the Great Blondin Ruled Niagara. She has several other books for young readers, and a great website: donnajanellbowman.com. The research I’ve shared, however, is my own. Bowman is responsible only for the facts she speaks to in her own voice.

Thank you again to The Hardtacks for the use of their song “Jordan is a Hard Road.” They also have a great website: CivilWarFolkMusic.Com which helped me understand the many versions, titles, and histories of this song.

The music you’re hearing now is from Holizna, slightly alter in parts for use in this podcast. All other music is from the Library of Congress.

Bowman: I even bought a length of rope from e-Bay once I figured out the size of the rope, and that was after getting some pretty interesting looks at Home Depot, a couple of different Home Depots, when I went in asking for a large hemp rope. It’s not something I would recommend, having been there, but I found a stretch of rope from e-Bay that I could put under my feet. Even though I wasn’t over a river or even elevated, I just needed to feel it under my feet, to put myself in Blondin’s shoes as much as possible.