Listen here. Full Transcript:

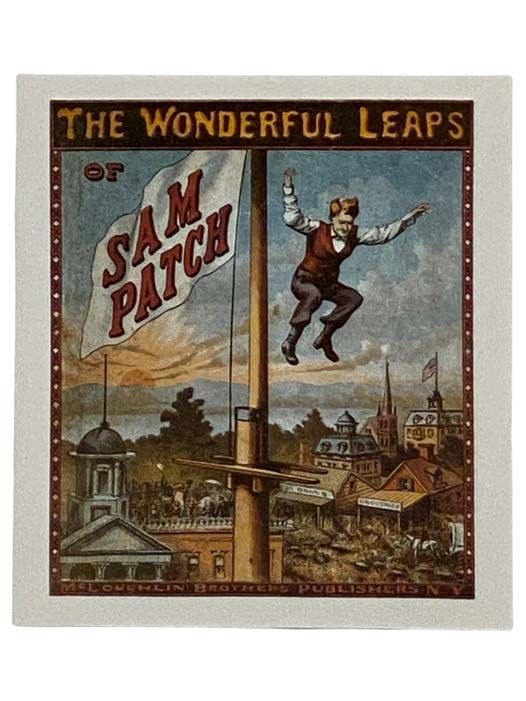

Before Evil Keneval or Harry Houdini, before P.T. Barnum’s circus, Sam Patch drew crowds of thousands who came to watch his dangerous leaps from the rooftops, waterfalls, cliffsides, the top of a ship mast, into the waters below. Patch was a drunk, a scoundrel, a roughneck millworker, a hero of the working class, and the first true American daredevil.

Over time, and after his death, Patch grew from a man to a myth. Stories about him twisted and changed. Patch was forced into political ideologies and made into cautionary warnings. His enigmatic catchphrase, “Some things can be done as well as others,” was a rallying cry, a proud proclamation of American grit. At the same time, he came to embody the very American folly of having a thirst for celebrity at any cost.

His jumps increased in difficulty and spectacle and his popularity grew. And, Just as Paul Bunyon had a blue Ox, Sam Patch had a pet bear who accompanied him to various taverns and at least once, made a leap along with Patch.

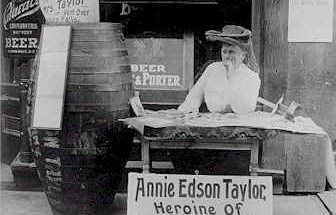

Like all great folk heroes, Sam Patch is memorialized in songs, poems, and in children’s books. President Andrew Jackson named his horse after him. Even today, Patch’s story is still being retold and reimagined. Why? What is it about Sam Patch, about daredevils in general, that is so intertwined with Americana? What is it about this story that necessitates its continual retelling? We’ll get into all of that in this episode.

PODCAST INTRO:

Welcome to the Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. In this podcast, we’ll examine the bravery, stupidity, hubris, and eccentricity of people who have attempted daring feats at Niagara Falls. My name is Theodore Carter. I’m an author whose novel research went too far, and I got swept up in the current of stranger-than-fiction stories surrounding Niagara Falls. Now, I’m putting that research into this podcast.

Born in 1799, Sam Patch spent his youth laboring in a mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island along with many other children. Patch grew up before child labor laws, and he worked long hours and was likely kept awake and alert by the occasional paternal smack from an overseeing spinner.

A Spinner was the chief operator of enormous textile machines called spinning mules that wove cotton into yarn. Running a spinning mule required several people, usually the spinner himself and several boys. These machines and the mills that housed them helped usher in the American Industrial Revolution.

After years of laboring as a child, Sam became a spinner himself, a respectable and decent-paying job for a man of humble beginnings like Sam. But Sam wanted something more, something grand.

The Pawtucket Falls, next to the mill, was also a gathering point for the town’s young boys. It was a swimming hole, a fishing spot, and the bridge running over the falls became a diving platform, a mainstage for youthful bravado as swimmers dropped fifty feet into the River. As the town grew up around the falls, new buildings provided new launching points for the jumpers creating new and more spectacular launch pads. Soon, the jumpers were taking off from 100 feet above the water. Sam Patch was one of these skilled jumpers. Crowds gathered to watch Patch and his friends. The responsible citizenry voiced opposition to this unseemly spectacle, and there was talk of forbidding such behavior, but the respectable people of Pawtucket couldn’t stop young men from leaping from high places into the river.

Sam Patch moved from Pawtucket to Patterson New Jersey and worked as a spinner next to the Passiac Falls, a beautiful, rocky 77ft tall waterfall, the second largest waterfall east of the Mississippi. Accounts from the time report that Sam, beaten down by busted business deals and hard work, had grown bitter and was frequently drunk.

When a local businessman Tim Crane touted the unveiling of a new bridge across the Passiac River that would lead to a hoity-toity park and restaurant, Patch vowed to steal his day. As the citizenry assembled to watch workers slide the new bridge into place with an elaborate system of ropes and floats, Sam Patch emerged perched high above the river. With a mighty leap, he stole Crane’s audience and positioned himself as a hero standing against all the aristocratic aires of people like Crane who were privatizing and monetizing the natural wilderness near the falls.

The poet William Carlos Williams retold this story of Patch’s jump at Passiac Falls in his 5-book epic poem “Paterson” published between 1946-1958. His version, which includes an account from an old man who was a supposed eyewitness to Patch’s jump, is included here.

When the word was given to haul the bridge across the chasm,

the crowd rent the air with cheers. But they had only pulled it halfway over when one of the roiling pins slid from the ropes into the

water below.

While all were expecting to see the big, clumsy bridge topple

over and land in the chasm, as quick as a flash a form leaped out

from the highest point and struck with a splash in the dark water

below, swam to the wooden pin and brought it ashore. This was

the starting point of Sam Patch’s career as a famous jumper. I saw

that, said the old man with satisfaction, and I don’t believe there is

another person in the town today who was an eye-witness of that

scene. These were the words that Sam Patch said: “Now, old Tim

Crane thinks he has done something great, but I can beat him.” As he

spoke he jumped.

There’s no mistake in Sam Patch!

“There’s no mistake in Sam Patch!” was one of Patch’s often-used slogans. Other reports have Sam Patch coining another one of his catchphrases on this day: “Some things can be done as well as others.

Patch became a hero of the everyman, and his feud with Crane continued. On July 4th, Crane sold tickets to a fireworks show on his private property. Patch scheduled another jump and drew a crowd of 3-5 thousand people according to newspaper estimates. The population of the entire town was around six thousand. Afterward, he passed a hat around and collected 13 dollars which is the equivalent of around $400 today. Crane may have netted more money with his event, but no doubt Sam won the hearts of the townspeople, especially the working class who likely could not have afforded Crane’s firework show.

Sam’s growing fame propelled him away from Paterson New Jersey to Hoboken New York where in 1828, likely drawn in by a local businessman, Patch made a 100-ft jump off the masthead of a ship into the Hudson River.

Not everyone enjoyed Patch’s brand of entertainment. New York Enquirer wrote:

“We remember a sleight-of-hand man, who was exhibiting his feats in a village in this state, much to the astonishment of the audience. At length, he said, “ Ladies and Gentlemen, I have one feat that will astonish you.” So saying, he spread a carpet on the floor and with a pistol very cooly blew his brains out. The villagers were very much tickled, but exceedingly grieved when they discovered that there was no sleight-of-hand in it.”

Sam Patch was low-brow. He was low-brow in the way P.T. Barnum was low-brow, the way popular theater at the time was low-brow, and while many condemned his feats as tawdry and grotesque, this certainly didn’t harm his popularity.

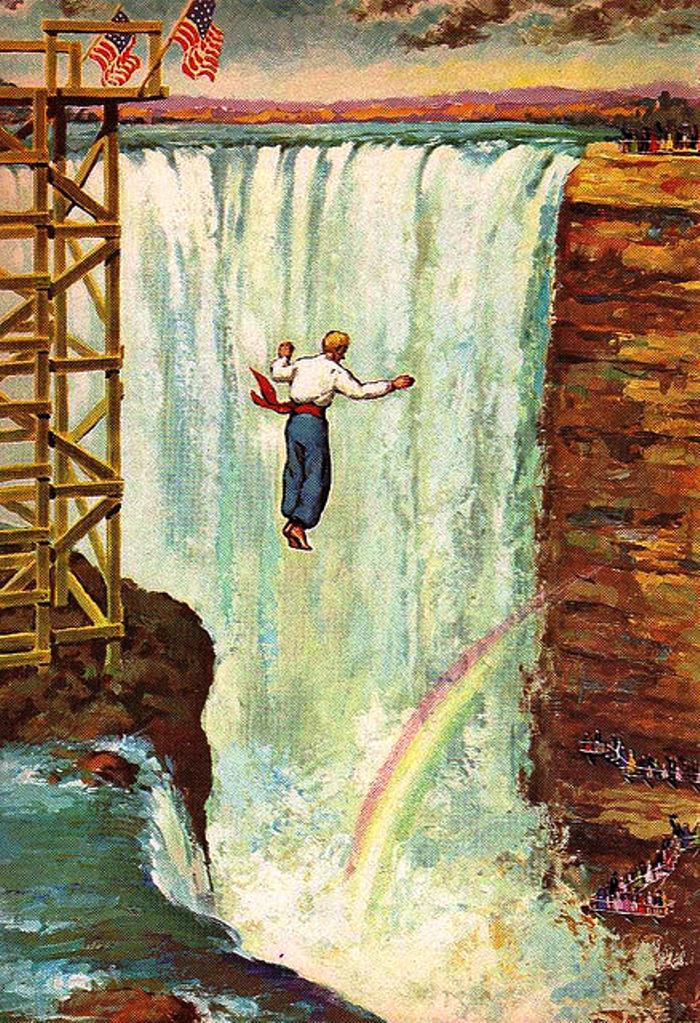

He became known as the Jersey Jumper, the Yankee Leaper and his growing popularity brought opportunity. A group of businessmen invited Patch to Niagara Falls. They planned a series of events that would include a dynamite blast of a nearby rock face, a ghost ship sent over the falls for sheer spectacle, and a leap off the falls from Patch. Patch agreed to the jump, and on October 6, 1829, thousands came by steamboat and by foot for the event. Vendors sold food and liquor, and circus performers and traveling acting troupes worked the crowd.

However, when time came for the series of spectacular events, the explosion paled in comparison to the steady tumult of the thundering falls leaving spectators underwhelmed. The ghost ship broke apart in the rough current of the Niagara River, capsized, and sank before going over the falls. Worst of all, Sam Patch didn’t show. It’s hard to imagine the crowd’s disappointment or the ire of the group of businessmen who had failed so spectacularly and publicly, but clearly, this did not go well. Some of this failure was the result of poor planning. Some was bad luck. However, Patch not showing up was a rather egregious offense one might think unforgivable.

Nonetheless, he did appear the next day, as did the crowd. Promoters of the event exploded several other rock faces along the river in coordination to make up for the previous day’s lackluster blast, and by all reports, the explosions were somewhat improved though still underwhelming. Sam climbed to his specially built platform above the falls, and this time made his historic leap.

This moment, I imagine, is where the magic lies for Sam Patch. There is something truly horrible about the idea of watching a man fall from heights that you know are likely to kill most people. “I came to watch this? Why did I come to watch this? What kind of person am I that I would come to watch a man do this? What if he dies?” We can think of a number of acts billed as “death-defying,” and all of them make use of these complex feelings of hope, awe, fear, and shame.

If I had been in the crowd as Sam Patch plunged into the Niagara River, I’d have been holding my breath for his safe return to shore not only for his sake but also to validate my own decency and prove that I did not come out of an immoral appetite for the grotesque.

Then, imagine being in a crowd of thousands assembled around the violent roar of the falls. And Imagine the relief you would feel, the collective exhalation you would have shared with those around you when a short time later, Sam Patch emerged from the white water below and swam safely to shore unaided, then stood on the rock singing out in celebration.

A few days later, Patch issued an announcement apologizing for missing his scheduled jump on October 6th but stated he felt it necessary to jump the following day to prove “That I was the TRUE SAM PATCH and to show that some things could be done as well as others.” He promised another jump at The Falls from a point 50 feet higher.

During his time in between jumps, Sam enjoyed his celebrity and the cavalcade of media attention. He was seen in Buffalo at parties and taverns, often drunk, entertaining his many curious admirers. He took to wearing a red silk sash and a sailor coat and made extra money as an exhibit at Johnathan McCleary’s Museum where patrons would pay for the opportunity to meet the famous daredevil. It was at this time too when Sam Patch acquired a pet ybvgy gFF, perhaps from McCleary which, while doubtlessly impractical, certainly furthered his mythological status. In subsequent poems and ballads, Patch’s bear became a prominent character and even narrated William Getz’s 1986 novel “Sam Patch: The Ballad of a Jumping Man.”

The excitement continued to build and build. So, on October 17, Sam Patch stood at the base of his elevated platform. He removed his shoes and sailor jacket and tied his silk sash tight to his waist. He ignored the dramatic pleas of onlookers warning him not to undertake the stunt. Thousands watched him climb a ladder extended out over the cliffside to a platform high above the pool. An American flag pinned atop the platform waved in the wind, and as Patch stood there on the border of America and Canada, his platform swaying precariously back and forth, he took a small corner of the flag and kissed it. Then, again, he jumped, straight and true, hands at his side. Again, the crowd held its collective breath, and again, he emerged from the depths below whole and unharmed. And Again, newspapers and the public debated whether he was great or grotesque, a brave everyman or a foolhardy drunk.

Shortly after his triumph at Niagara, patch announced that he would make a 100-foot jump at Genessee Falls, on November 6th, which, advertisements point out, is tactfully after election day. “Let every man do his duty at the Polls, and Sam afterward will do his at the Falls.” reads the ad. It went on to state that those interested in the miraculous jump could buy subscription papers at several Rochester taverns.

Sam and his bear secured lodging in the Rochester Recess, a pet-friendly establishment offering lodging, pickled oysters, candy, hot meals, and a fully stocked bar. His bill was paid, according to historian Richard M. Dorson, by “A group of local sportsmen accustomed to patronizing boxers, gymnasts, and wrestlers. The Recess also sold instruments and was a center for a local musical tradition which included the Rochester Band. The Band, while they did perform music, was more like a fraternal drinking club open to any white man willing to pick up an instrument and included many of Rochester’s leading businessmen.

One can imagine Patch holding court in the saloon of the Rochester Recess, drinking beer and eating pickled oysters amidst lots of drunken laughter and a cacophony of brass and drums. When not drinking, socializing, and taking care of his pet bear, Sam made scouting missions out to the falls to examine its properties and make whatever observations Sam Patch made before leaping from great heights.

The population of Rochester at the time was about 8,000, while estimates of the crowd assembled to watch Sam Patch’s jump range from 6-10,000. Based on reports of the circus-like atmosphere of the crowd that assembled for Patch in Niagara, it’s likely that the Rochester crowd was similarly raucous and eclectic, the city elite mixing with rough and tumble mill workers who knew of Patch from tavern talk.

Sam arrived leading his pet bear by a chain. Finding his spot on the limestone overlook, he bowed to the crowd and took a sash from his head, and tied it to his waist, a splash of color reminiscent of his showmanship in Niagara. What was new and different was that before he made his leap, Patch pushed his bear off the ledge. The bear splashed into the river below and swam safely to shore. Next, Sam did the same, spurned the boat poised to help him and making his way out of the river to proclaim “Some things can be done as well as others.”

There is no account of whether or not Patch attempted to collect his pet bear, and I could not find evidence of the bear making a second leap. I really got sidetracked with some bear research here but to no avail. I’m forced into conjecture. It’s possible that it’s not easy to gain the trust of a bear after thrusting it off a 100-foot ledge, and that proximity to a bear that does not trust you is more dangerous than leaping over waterfalls.

So, now likely without a pet to care for, Patch could focus on capitalizing on the fervor he’d created and soon advertised another leap that would make use of a 25-foot platform to place him even high above the river. In addition, he’d jump on Friday the 13th, defying superstition. Posted advertisements appear not only in Rochester, but in neighboring towns as well. Schooners and coaches brought the curious from nearby counties, and the Rochester hotels filed up. On the morning of the 13th, grocery stores and whiskey purveyors did brisk business. Estimates put the crowd size at 12,000 people, and as the time for the scheduled jump approached, they lined the streets and sat on rooftops waiting for Sam Patch. Someone passed a hat around to collect money for the performer.

Patch spent the morning drinking at the Rochester Recess, and receiving gifts from his new friends including a black silk sash which he tied around his waist, and white band uniform pants that paired nicely with his sailor jacket. Then, he emerged from the hotel with his entourage and processed toward the falls. His walk turned into a parade as the crowd made their way to his platform with him, the town aristocrats, scoundrels, working men, women, and children all cheered as Sam Patch moved to the base of his newly constructed jumping platform.

Several accounts, perhaps colored by hindsight but likely given Sam’s reputation, state that Sam was clearly drunk, that he didn’t move well, and that even standing still, he appeared to sway back and forth. He gave a speech to the crowd, the content of which, by all accounts, was unremarkable and nonsensical. Then, he climbed atop his platform and jumped.

Undoubtedly, the crowd held its collective breath. Then, during his descent, something went wrong. Instead of his usual arrow-straight plummet, Sam’s body tilted. He flailed his arms and hit the water awkwardly. The crowd waited for him to emerge, to see him defy the odds again and proclaim, “Make no mistake, I am the real Sam Patch! Some things can be done as well as others.” Instead, nothing. He did not emerge from the river to allow the crowd a collective exhale or joyous moment of disbelief.

There are no accounts of how long the crowd stay assembled or who scrambled down toward the river to check and see what had happened. There’s no reporting on what parents said to their children as they walked away from the falls after realizing they’d watch a man plummet to his death, or what those out-of-towners said to one another as they rode their coaches back toward their homes. One can imagine the sad aftermath in the streets of Rochester after having been overrun by a crowd greater than its population: the empty bottles, crusts of food, and lonely Sam Patch handbills still posted around the city. It’s unclear what happened to the hat full of coins collected for Patch or the money paid to tavern owners for subscription papers.

This jump at Genessee Falls was Sam Patch’s final jump, the one he didn’t survive. However, this is also only part of Sam Patch’s story. His fame continued to grow and he became more famous in death than he ever had been in life. Patch became an allegory, a folk hero, and the poems, and songs about Patch were just beginning. More on that in the next episode.

Thank you for listening to The Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. If you’re enjoying the show, please write a review and tell a friend. Also, please consider connecting on social media. On Twitter and Instagram, I’m theodorecarter2. I’m also on Facebook as well, and there, you can join the public group “Niagara Falls Daredevils” to share your own stories and engage in discussions with others. This show is just me. There’s no funding behind it or other people behind the scenes. So, I’d love to hear from you to know more about what you enjoy, what you think I got wrong, or which daredevil I should research next.

While I consulted many sources in the creation of this podcast, I’d like to mention two specifically because they were the best and the two I referred back to most frequently. The first Is Paul E. Johnson’s book “Sam Patch, The famous jumper.”

The other is Richard M. Dorson’s article, “Sam Patch: Jumping Hero.”

Thank you for listening, and please visit the museum again.

Afterward, no one could find Sam Patch’s body. Perhaps he’d faked his death, scrambled to shore unnoticed, and would at some point reappear having pulled off the most remarkable stunt of his career. Others took this opportunity to again opine about Patch’s ghastly and distasteful antics. He became the subject of cautionary sermons and mocked for a vanity that lead to his death.

And, just as rumors continue that Elvis and Tupac faked their deaths, there were many who refused to believe Sam Patch had died, especially without evidence of a body. People claimed to have seen him or to have heard others had seen him, in Rochester, in Manhattan, and elsewhere. An announcement appeared in the New York Post on November 30th with the headline “Sam Patch Alive!”The text, supposedly written by Patch himself included a heavy sprinkling of his catchphrase, “Make no mistake, I am the real Sam Path,” and “some things, you see, can be done as well as others; and I am resolved to let the world know that I am still alive and kicking. It was a capital hoax though, wasn’t it?

Sam had been scheduled to give a talk at a tavern on December 3rd, and many showed up on the appointed day thinking he’d show. He did not. Adding to the confusion, several newspapers published a story about Patch’s body being found in the Genessee, but these reports proved to be false.

Then, in March of 1830, Silas Hudson a hotel worker, walked his employer’s horses to the river to drink at the mouth of the Genessee near Lake Ontario. Because the water was frozen, he kicked through the ice with his boot. When he did, the body of Sam Patch bobbed to the surface still in the black silk waist sash and white Rochester band pants he’d worn during his final jump six miles away.

However, even this did not put the matter to rest. Nathaniel Hawthorne came through Rochester several years later, and in an 1835 essay wrote about locals still denying Patch’s death.

Strange as it may appear–that any uncertainty should rest upon his fate, which was consummated in the sight of thousands-many will tell you that the illustrious Patch concealed himself in a cave under the falls, and has continued to enjoy posthumous renown, without foregoing the comforts of this present life.

Like many American celebrities, from Robert Johnson to James Dean, Sam Patch became more popular after his death. A Library of Congress newspaper search turns up just a few mentions of Patch during his lifetime, but nearly three hundred mentions of the name in the second half of the 19th Century.

Andrew Jackson named his new horse Sam Patch in 1833, and historian Paul E. Johnson delves deep into the importance of Sam Patch’s legacy at the time of Jackson’s populist rise. Patch was a symbol of rugged individualism, a poor man who rose to fame out of sheer grit and gusto. Johnson also points out that this period in American history also saw a boon in newspapers and printing, which no doubt made myth-making easier.

Whatever the reason, nationalism, and American myth-making were having a moment in the middle of the 1800s. Davey Crocket died within a few years of Patch, and his life began to take on legendary status shortly afterward. Johnny Appleseed had become a mix of fact and fiction before his death in 1845, and afterward, he grew into a folk hero. Paul Bunyon stories began circulating around 1860 in logging bunkhouses. The real John Henry, on whom his stories are based, was born in 1848.

Though Sam Patch did not become a household name, his legacy has endured. Sure, he’s more firmly in the fabric of the history of New York state than in the country as a whole. Even so, still today, people continue to tell stories about him and to write poems and songs about him.

This is end, the final plummet, in the telling of this story. Whatever I have to say to summarize the Sam Patch story Hawthorne wrote about Patch’s legacy, so I’m going with Hawthorne

He will not be seen again, unless his ghost, in such a twilight as when I was there, should emerge from the foam, and vanish among the shadows that fall from cliff to cliff. How stern a moral may be drawn from the story of poor Sam Patch! Why do we call him a madman or a fool, when he has left his memory around the falls of the Genessee, more permanently than if the letters of his name had been hewn into the forehead of the precipice? Was the leaper of cataracts more mad or foolish than other men who throw away life, or misspend it in pursuit of empty fame, and seldom so triumphantly as he? That which he won is as invaluable as any, except the unsought glory, spreading, like the rich perfume of richer fruit, from virtuous and useful deeds.