I met Clarke Bedford as he readied his steampunk art car, Vanadu, for the Takoma Park Fourth of July Parade. Bedford invited me to his home in Hyattsville, MD which, like his van, is a work of art.

Up until his recent retirement, Bedford was a conservator of paintings and mixed-media objects at The Hirshhorn Museum all the while creating sculptures, paintings, photographs, and other more difficult to define works of art.

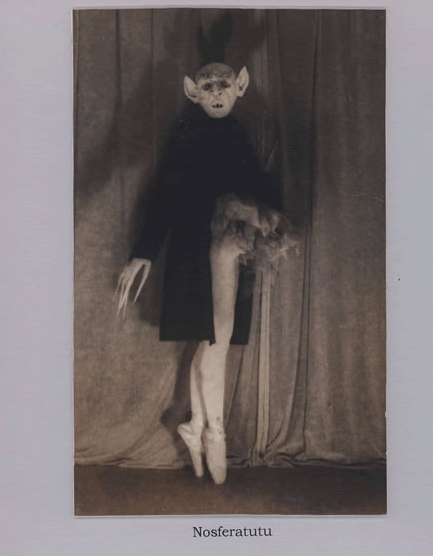

He’s created fictional characters with full histories and accompanying art such as Frederick Draper Kalley, the “Prince of the American Renaissance” and a fantastic version of Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman who tries to find peace post-war by moving to the suburbs and marrying a giant fertility idol.

Bedford also created “A brief description of the Argyle Sock -and other Laundry Imagery- in Modern Art,” an entire series of sock art satirizing famous masterpieces.

Bedford has shown work in several galleries in the area, lectured at universities and museums, and has been featured in The Baltimore Sun, The Washington Post, and The Washington City Paper. Here, he takes time to answer some of my questions.

What kinds of reactions do you get when you are out in your cars?

I see a lot of surprised and wide-eyed, oh-my-gosh smiles and laughter. The reactions are those of kids even from non-kids. I assume that’s because the cars are outrageous, and large, or at least tall. In this area, many people don’t know the concept of an “art car” so the cars seem all the more outlandish.

Some old guys are into the vintage auto elements. I’m always astonished by the number of people who know so little about cars that they see the Cadillac fenders and think the van itself is a Cadillac. Or, they’ll ask about the year thinking it must be really old (as in what, 1880?).

It can become a problem when others slow down to take pictures. It interrupts timing for merging into traffic.

Your house looks like a museum or gallery. What does it feel like to live in your own art? What do the neighbors say?

I feel comfortable. Even more than that, I feel safe in my own house. I grew up in suburbia, but not in a spic-and-span type house. I feel queasy when I see places with each and every detail so impersonal and perfect.

I don’t see my house as a museum, just layered in the manner of the 19th century salon style. I like to look at stuff and need a lot to look at. The aesthetic of severity is to me just death. The neighbors seem to get it, but then this neighborhood is forgiving. Generally, the more prestigious the area, the more conformist it is.

Three or four people said they decided to move to our street because of my house. I don’t know why virtually all houses and cars are so dull. The Post will have a story about a couple in Bethesda who (amazing!) cull out a playroom from a nook in the basement, as though that was so adventuresome. It’s a mystery to me.

You’ve created entire narratives around fictional artists. Why did you create these personas?

I don’t know why. There might be deep-seated escapist tendencies there, a fundamental doubt about oneself, a search for authenticity? It’s theatrical I guess, like Monty Python. An extreme of the type might be Andy Kauffman. I grew up with old school satire, very British. I do mimics fairly well and like to go into character, so inventing a life around that is natural.

What is the roll of humor in art? Is art funny?

No, generally, I don’t think art is funny. Pushing humor in art is one of my contrarian challenges precisely because there is so little of it, yet many a notable person (you can find many famous quotes) will acknowledge the importance of humor in making ones way through life.

One of the pieces I did for the “Wundergarten” show at Hillyer Art Space was an assemblage of a print of the painting of The Riddle of the Sphinx by Ingres. The famous riddle being, “what walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three in the evening.” The answer is man in his various stages of life. In my assemblage I included photos of one of the family members as a baby, adult, and an old man. One curator friend laughed out loud, and another found it very sad. So there you are. Humor, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

Dada is clearly humorous I think, in a bleak way, but some don’t find it so. Outsider art is the same. Theatre has comedy and tragedy, but not visual arts. A commonly used term to laud a work of art or an artist is “important,” a word which cannot connote humor. It would sound awfully heavy to say, “Steve Martin is an important comedian.” Film gets to blend humor and pathos because it is an extended form. I always find pretentiousness humorous, and a lot of contemporary art is pretentious so I find it humorous. I know it is not intended to be. Same with weddings.

How did your work as a conservator influence your own art?

Conservation is based on objectivity rather than subjectivity which is rare in the art world. A work of art looks a certain way because it was made that way, and understanding how it was made helps to understand it aesthetically. It can be remarkably like forgery without the benefits and risk, and is consequently a bit subversive. Many an art historian has waxed on about an area of a painting that was old restoration. Obviously, my knowledge of art and artists increased enormously because of the job as well as my understanding of materials and techniques. This helped me make my own art more efficiently.The fact that I do different things may be related to this. I know a lot about different art.

What are you most proud of as an artist?

I’ve made art my entire life. I started as a kid and I’m still doing it. That may be dedication, desperation, or addiction. Whatever it is, I haven’t stopped and that hasn’t always been easy. I lived in Baltimore for seven years while commuting to the National Mall on top of a twelve-hour work day. Still, I managed to put in an hour or two each night. I’ve received some cool reviews and people seem to like the work, but the hardest thing is just to keep going even when it seems pointless.

What do you hope to accomplish next?

I’m constructing a mini set up which I plan to transport and show with Vanadu, a sort of traveling side show “Fauxseum.” The house remains the “mothership,” but this will be an extension of it.

What do people commonly get wrong about your work?

Getting things “wrong.” That would apply to anyone who does anything personally expressive presumably.

I don’t think what I do is obscure, but rather, the more you’re familiar with source material, the more you will get out of it. Someone might say Vanadu reminds them of having a van in the ’70’s when nothing could be less related, aesthetically at least.

I screw myself artistically by synthesizing niches rather than fitting into one. The outsider/assemblage balance can be misinterpreted. My efforts contain elements of both. People like a single answer, and I am not so interested in providing one.

You can find out more about Clarke Bedford by going to his website.

Click a picture to enlarge and begin a slide show of Bedford’s home.

One Comment on “Clarke Bedford on Art Cars, Humor in Visual Art, and Comfort in Nonconformity”

Comments are closed.