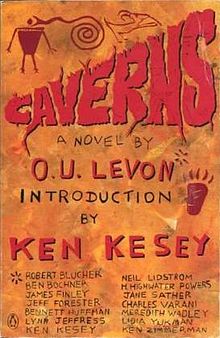

During the academic year of 1987-1988, Ken Kesey taught a graduate-level creative writing class of thirteen students at the University of Oregon. He charged the group with producing a full-length novel in one school year, which they did, publishing Caverns under the name O.U. Levon (Novel University of Oregon backwards) in 1990.

It is my intent to interview each living author about the project and what they learned from Kesey. I outline the project in more detail in my initial posting and provide links to the other interviews.

Ben Bochner’s interview is the seventh I’ve published, and it’s the longest. When contacting each living co-author, I supplied a list of simple questions, a form all previous respondents used, more or less. However, I also told each that deviations from the script were welcome.

Bochner responded to my initial emails with some off-the-record background about his story, how he unwittingly infuriated Ken Kesey, a man whom he admired and had wanted so badly to please. As evidence, he pointed me to a Paris Review interview published in 1995 where Kesey delivers one of his most famous quotes, one that would be repeated frequently in articles about Kesey for years to come: “The answer is never the answer. What’s really interesting is the mystery.”

The lead in to this quote is a story about Bochner: “When I was working on Caverns, I found out that one of the problems was that students kept looking for the answers to symbolic riddles and believed that modern fiction is supposed to supply you with the answer.” Later in the interview, he says of Bochner, “…the class was just ready to string him up. What are you gonna do to him? someone asked. I said, We’re not gonna do anything. We’re not gonna talk about it. We won’t speak of it. We will not ever speak again of this to him at all.”

Later, Bochner learned he’d become a frequent anecdote in subsequent Kesey interviews and campus lectures which always ended with Kesey quoting the climatic lines from the Paris Review interview:

“It’s the job of the writer in America to say, Fuck you, God, fuck you and the Old Testament that you rode in on, fuck you. The job of the writer is to kiss no ass, no matter how big and holy and white and tempting and powerful. Anytime anybody comes to you and says, “Write my advertisement, be my ad manager,” tell him, “Fuck you.” The job is always to be exposing God as the crook, as the sleaze ball.”

Years later, Kesey’s biographer would ask Bochner, “How does it feel to be infamous?”

Bochner didn’t feel his story fit with my prefabricated questions and asked that we begin a conversation over email.

Below is an amalgamation of approximately 35 emails I exchanged with Bochner. It’s the first time he’s detailed his account of how he became Ken Kesey’s “Rogue Reader.”

What were your thoughts upon seeing Kesey that first day of class and hearing his idea about cooperatively writing a book in one academic year?

I do believe the first thing that impressed me about Kesey was how pink he was. The guy who came barreling in was a big Nordic bear, sweating and red-faced, giving off a pleasant odor of fresh straw. He poured himself a glass of water, lapped it up – like a bear! – and launched into his idea for writing a group novel.

I was surprised by the gentleness of his voice. It was smaller than what I’d expected out of a man of that size, softer than I’d been led to expect from his heroic portrayal in the media. It was intimate and had just a hint of a country accent to it. That fresh straw, again.

If I remember correctly, he started the whole thing by performing a magic trick, to illustrate his belief that magic is the basis of all art. I was thrilled beyond my wildest imagination because all I’d known at that point was that he was teaching a novel writing class. Now it turned out I was going to actually write a novel with one of the greatest novelists of all time! It was like finding out I was going to write a symphony with Beethoven.

Do remember the magic trick he performed?

You know, I was thinking about that, and it doesn’t quite come clear. I’m pretty sure he made a coin disappear. I saw him do a couple of magic tricks over the years, and I guess they’ve blended together. Others in the class may remember better than I do. I guess it really doesn’t matter. A good storyteller forces you to suspend your sense of disbelief, right? I think that’s what he was getting at. Kesey hated boring, navel-gazing, overly psychological storytelling. He wanted writers to be magicians who dazzled him, not intellectuals shrinking everything into dust.

Was Kesey able to keep that magic alive as the class got underway and you all began to write?Ironically enough, in light of the fact that I ended up so “off the bus,” I felt there was an undertow of passivity in the class as a whole. This is actually quite a complex dynamic, since each person had their own background and their own context for seeing things. As far as I was concerned, I’d been a believer ever since reading Cuckoo’s Nest in high school. But I remember being surprised at a sort of bureaucratic mindset among the students, an over-concern with grades and how the class would affect their work in other classes and their chances at a future job.

But, like I say, we all had our own prisms. In my case, I had dropped my other classes and was concentrating on the novel writing class. For the others, Kesey’s was just one class on a full slate. In any case, there was a spectrum of engagement. Some people seemed quite skeptical of the counter-culture icon. It was the 80’s. Reagan was president. Nancy Reagan was telling people to just say no. But Kesey is a charismatic character and a genuinely big-hearted guy. He eventually won everybody over. Kesey was also a natural-born politico, and he consciously courted potential adversaries.

I read one time where Arthur Miller, the playwright, said charisma isn’t the ability to make people like you, it’s the ability to make people want you to like them. Kesey had this in spades. Kesey was the most Tom Sawyer-like person I ever met and most people who came in contact with him were only too happy to help him paint his fence.

I do think people held back a little. It wasn’t their ass on the line if the group novel failed. But it was so fun, just showing up at his house twice a week, perusing the buffet that Faye put out, drinking wine, and listening to Kesey’s tales of psychedelic and literary celebrity. How could one not be seduced by the glamour of it all?

Did you get the sense that Kesey’s ass was on the line? Did he/you have an audience watching before you even started?

Not really. I personally didn’t think he was in that much of a slump. As I said, he seemed in the pink to me. Still in his prime. I mean, Demon Box wasn’t Cuckoo’s Nest, but not much is.

It was only later, as I heard scuttlebutt, that I got the feeling he might have needed a boost. He kind of said as much right from the beginning, when the character he brought into the novel was a magician who’d lost his mojo. I had a feeling I was in for an interesting ride when his magician character, my reality-creating murderer, and Neil Lidstrom’s Doctor of Anthropology got rolled into our lead character, Dr. Charles Oswald Loach.

Loach’s entire journey into the cave is a redemption story. So, even though there was no overt discussion about Kesey’s ass being on the line, looking back it’s pretty clear. We also learned at some point that Kesey owed Viking a book (since he’d stopped writing Sailor Song). It had been a while since he’d had a big book, and 10 years since “Cuckoo’s Nest” won the Academy Award for Best Picture. I do believe Kesey’s team at Sterling Lord Literistic wanted something to keep him in the public eye, though for the details of that you’d probably have to talk to David Stanford (Kesey’s editor at Viking). Amongst the rumors we heard was that Viking was adamant that Caverns was not to be that book. But there was a sense that Kesey needed something to jump-start him. He was still reeling from the loss of his son, Jed, a star wrestler at the University of Oregon, whose bus had gone off an icy road in the Cascade mountains. He told us many times that the grief of losing his son had almost killed him.

When you got deep into the project, did you feel it would work? What was your outlook and what was the outlook like for the group?

When you got deep into the project, did you feel it would work? What was your outlook and what was the outlook like for the group?

There were three distinct phases in the writing of the book. The research, the first attempts at writing, and the final stage where we wrote each chapter together.

During the first attempts, it was hard to picture everything coming together. We had lots of great bull sessions in which people talked about the things that most interested them, things they’d like to write about. We all seemed to have a little piece of the zeitgeist that fascinated us, and they intersected in things like the rise of fascism in the early 20th century, the power of myth, the breakdown of traditional religions, the rise in the occult and a concept Kesey called The American Terror, a kind of black hole in the American Dream where we’d buried our guilt about what we did to the Indians, African-Americans, Hawaii, Guatemala, Vietnam and…you get the idea. This hole became our Secret Cave of American Ancients, and, for a while, all we knew about our novel was our characters were going to go down into it. Just figuring out this much took us a few months. Then, our individual attempts at writing the early chapters proved to be slow and disjointed as we each wrote in our own style.

But then, the idea of each person merely outlining a chapter, then all of us sitting around a table together, fleshing out the outline, and reading fresh pages into a tape recorder, seemed to work. We’d come out of these sessions with only a rough draft, but the act of being in the room together and writing for a pre-determined amount of time (about an hour) seemed to cut through a lot of the problems that we’d had. No longer could each of us procrastinate and pontificate and weave our little stylistic curlicues. We were responsible for moving the action from point A to point B and we’d have to do it front of each other immediately after writing.

This pressure seemed to bring out the best in us. We all knew how to play to the room. What we started to get were not deep Tolstoyan meditations on the human condition, but sitcom blocking and cartoon dialogue. All of a sudden, the most important skill you could have was to make people laugh. We were forced to actually entertain each other, and this really helped the story snap into shape. When you’re sitting alone in a room, getting a sentence jiggered just right seems important. When you’re telling a story to a group of people, nobody gives a shit how your sentences are jiggered. This approach may have doomed us to sitcom writing, but at least the thing was moving. There was always time to go back and fix things later. It was great, because writing became fun again.

Unfortunately, we discovered this method very late. Once we hit upon this way of working, a lot of chapters got written very quickly. Still, we were up against a deadline – the public reading we’d scheduled at Gerlinger Hall, on the U of O. We didn’t get to the final chapter until a few days before the reading, and it was very slap-dash and unsatisfying. But, all we needed was a placeholder. We figured we’d work it more after the reading.

It’s long been my feeling that we actually did come up with a great way of working together and that, if we did it again, we could come up with a very good book. Unfortunately, Caverns was our first attempt, and we didn’t know each other well enough to really hit on all cylinders. People seem to assume that because Caverns isn’t a very good book, the concept of group-writing doesn’t work. If Caverns had taken place in private and we’d had the sense (and the leisure) to rip it up, throw it away, chalk it up to experience, and start over, I think we could have produced something special. Of course there was no time for that. The class ended just as we figured out how to write together. Caverns ended up being a blueprint for a great book rather than being a great book itself.

How did the deadline of the public reading and the hype around it affect the ending of the book?

Sometime in the spring, we got word from Viking that the book was going to be published. We had not finished it, but apparently whatever needs to happen with the marketing gods in NY had happened, and they had given the green light to Kesey’s latest project. Then reporters started showing up from Rolling Stone, from Us Magazine, from national TV shows. It really sunk in that this thing was gonna happen. And Kesey was masterful at donning his top hat and putting on a show. He always had good one-liners ready for the reporters; nice, mystical, aw-shucks koans delivered in that soft Oregon accent that hinted he knew something about America that nobody else did.

What’s that old cliché? Nothing focuses a person’s mind like the prospect of hanging? That would overstate the level of my focus, but I did feel personal responsibility for getting the end of the book right. I had been given the job of writing the outline for the last chapter, and I spent a lot of time ruminating about what was going to happen to our characters trapped in the bowels of the cave.

The way I saw it, Loach had a lot to answer for. Although we had treated him as a lovable con man throughout the book, the fact was, he was still a con man and had organized this trek down into the cave for purposes of his own glory. He knew the “ancient” cave paintings were fake (his brother had painted them). Surely the amateurish nature of the hieroglyphics Dogeye had slapped on the walls would reveal Loach and his theories of an ancient American civilization to be a fraud. Now the group was stuck in that cave and it looked like they were all going to die. For what? For a con man’s vanity? It seemed to me that the only way to redeem Loach was for him to repent, to see the error of his ways, to take responsibility for the lies that had led to the groups’ immanent death.

And so I wrote a soliloquy for Loach in which he was his own most perfervid prosecutor. He hauled himself into the docket of his own mind, there in the darkness of the cave, delineating the details of every crime he charged himself with. One after the other, his deeds flashed before him in the dark – the lying, the self-promotion, the avarice, the betrayal – as well as the effect of his actions upon the people who had believed in him. It was a thorough horse-whipping Loach delivered upon his own being and a kind of introspective writing that had heretofore been nowhere in our farcical romp.

And then, after I’d spilled Loach’s confession all over the page and he was ready to meet his maker, then…

What?

For the life of me, I could not see what happened to our characters stuck in this tomb-like cave. I racked my brain looking for a way out. Did someone discover a crack that led to a shaft of light? Too corny. Did someone come down and rescue them? Did one of our quirky characters reveal a previously undisclosed expertise in spelunking rescue? Did they all just die? No scenario I tried seemed to work. Everything seemed forced and trite and contrived. I knew that every satisfying book I’d ever read had an ending that was both totally unexpected and, in retrospect, totally inevitable. There had to be a solution to this puzzle. But I could not figure out what it was.

And so, after many restless days and nights, I brought my outline for the last chapter of the book to the second-to-last class before the reading.

And it didn’t have an ending.

I arrived at class feeling like I’d failed. Whatever the answer to the puzzle was going to be, it was going to have to be discovered by the group as a whole, because I had struck out. I was disappointed in myself, feeling I’d let down both Kesey and the group, but maybe the answer was in the group mind itself. Maybe that was the key to ending the book. It couldn’t come from one person pacing up and down in the isolation of his own darkened room. Maybe we were meant to discover our ending together, in the act of writing. Maybe the meaning of our group novel could only be found in the act of group writing itself.

So, I did my thing. I laid out what I had. Nobody seemed overly concerned that there was no climactic ending. We simply divvied up the outline, assigned ourselves chunks of plot to flesh out and got to work. Kesey took the end part.

We wrote for our usual period of about an hour, then read our parts into the tape recorder. When we got to the end, all eyes were on Kesey. Instead of some great piece of writing that made the story fall into place like tumblers in a lock, all he wrote was, all of a sudden, the top of the cave crumbled away, and there was Dogeye, lowering a rope to get everybody out.

This was an ending so lame, so amateurish, that I’d discarded it from the very beginning of my rumination. I was flabbergasted, gob-smacked, amazed, disappointed. When people questioned the unsatisfactory nature of this non-ending, Kesey brushed it aside, quoting Joseph Campbell saying that the meaning is always in the journey, never in the destination. Yeah…but…God can’t just….pull the top off the cave…and let everybody out! That’s cheating! That’s like how a fifth-grader would end a story! Houdini can’t announce he’s gonna escape from a trunk at the bottom of the ocean and then just emerge from a trunk onstage and say “it’s the journey not the destination!” Nobody’s gonna buy that!

“Hush,” said Kesey. “We’ll fix it next class.”

Well, OK, you’re the famous writer, I said to myself. I was actually relieved. The burden of ending the book was no longer on my shoulders. Kesey said we’d fix it in the next class, we’d fix it in the next class.

The next class came, and I was eager to get to work. I was ready for Mighty Kesey to step to the plate and hit the ball out of the park. I couldn’t wait to see how he, and we as a group, would pull it off.

But instead of getting to work on the writing, Kesey prowled around like a nervous animal. He obviously had been working on something and it was weighing heavily on his mind. As we settled into our chairs, Kesey began to launch into the most inspired pep talk I’d ever heard. I mean, in movies, in books, from my old high school coaches, I’d never heard anything as inspired and impassioned and just plain right-on as this. It thrilled me to the marrow of my bones. It was the Fuck You to God speech that he was later to immortalize in the Paris Review interview. He had clearly given it a lot of thought. Maybe even stayed up all night, composing this battle cry for his troops. He started out by saying writing is a noble calling, even if you’re only writing menus, and it beats flipping burgers at McDonald’s! His face turned red, his arms flailed, and he said, “I want you guys to be the winners! That’s what Cowley taught me and McMurtry and Bob Stone at Stanford: Somebody’s gonna create the culture for the next 50 years and I want it to be you! Don’t just dream about it, don’t stick a manuscript in a drawer and say, Well, I gave it a try, maybe someday I’ll give it another go. Do it! Grab the brass ring!” Then he said we were all good writers, better than him, even, and because of that, some day God was gonna appear to us in all his Godly glory. He said stuff about how His nipples were gonna be like shiny red raspberries, and how he was gonna have a long beard and robes and all that, how he was gonna look just like Charlton Heston and he was gonna command us to write advertisements for him. Don’t do it! Kesey said. Don’t ever kiss any ass, no matter how big and white and smooth it is! Then he talked about Nelson Algren, how Algren had said the job of the writer is to pull the judge down into the dock, to make the high and mighty feel what it’s like to be down low. And then, he raised one big pink ham of a hand, stuck out his middle finger and said, When there’s injustice in the world, you gotta say, Fuck you, God! Fuck you and the Old Testament you rode in on! That’s the job of the writer in America!

(Kesey’s refers to this speech in his Paris Review interview, though Kesey’s reporting of the timing and purpose of the speech varies from what Bochner tells us here. Kesey says he gave the speech in order to protect the “Rogue Reader” after the public event.)

I was dazzled. One of the mottos of our ex-carny Dr. Loach was, “You Pays Your Money, You Takes Your Chances.” Well, I was ready to take my chances on Ken Kesey. Whatever he was selling, I was buying. He had me, hook, line and sinker. That speech seemed to sum up everything I’d ever learned from every writer I’d ever devoured, from Vonnegut to Tolstoy to William Burroughs. I don’t know what other people were thinking, but I was ready to go out on the field and hit somebody.

After he finished the speech, there was little time to do any actual writing. Besides, the speech had been so big, so emphatic, so over-the-top, that re-arranging words on pieces of paper hardly seemed like the appropriate action. Certainly there must be a hill to take! A beach to storm! An enemy to attack! But…no. Kesey the Elder had spent the night peering into the akashic records, plucked out the teaching he wanted to impart to his students, to all humanity! That was that. We went over the chapter. We pushed words around. Kesey wrote a Sometimes A Great Notion-like epilogue to end the book and tie the loose threads together.

But that lame non-ending was still there, throbbing like a hemorrhoid at the base of my brain.

I couldn’t believe it.

Class ended, people drifted away, and that was it. The next time we’d see each other would be at the reading.

When you say “Kesey was masterful at putting on his top hat and putting on a show,” you mean that both literally and figuratively, right? What happened the night of the reading? What was the scene like and how did it go down?

Ken Kesey was essentially a ringmaster. Writing books was just one of his feats of derring-do. Now, for your entertainment, ladies and gentlemen, watch The Great Writer pen the greatest novel of his generation! Now watch as he puts his head in the mouth of a Man-Eating Lion! Ken Kesey could have been an Olympic gold medal wrestler or president of the United States.

I wouldn’t have been surprised if one day he’d announced he was going to be shot out of a cannon. In a sense, he was shot out of a cannon, if you think about his adventures with LSD. In another age, Kesey might have claimed to have found golden tablets shown to him by The Angel Moroni and started a new religion. But he would have had a sense of humor about it.

The reading was fun. It had that Kesey sense of showmanship. We all dressed up in 30’s attire, lined up across the front of the room, getting up one-by-one to read a chunk of the chapter we’d been responsible for. The manuscript was in a wooden box on a table next to the podium. Kesey was resplendent in top hat and tails. I don’t know what kind of 30’s character I thought I was portraying, but I wore a frilly tuxedo shirt I’d found at The Goodwill, a tuxedo jacket with a red rose in the lapel and faded black jeans, ripped at the knee. These were also the days when I had a Jew-fro and a shaggy goatee. I guess I looked like a rogue.

Anyway, the event started to seem more like a high school play than a literary reading. We were up there in front of our friends and family. That was the big deal, not the book we’d written. After the initial charm of our costumes wore off, there was nothing for the audience to focus on except the story. And, to put it bluntly, the story wasn’t that good. The characters were whacky, the dialogue was old-timey, the young writers were fresh-faced and winning, but nothing really connected. There was a certain passion missing and in its’ stead was a kind of smirk. Maybe what was on display was the impossibility of writing a group novel. No one seemed that invested. Obviously, this book was full of good ideas and interesting concepts and the best intentions, but it dragged.

When I got up to read the last chapter, I still wasn’t sure what I was going to do. But my mind was still burning with the coals of Kesey’s sermon. When I got to the podium, instead of reaching into the wooden box to take out the chapter we’d written in class, I reached into my pocket and pulled out the pages I’d written. I just couldn’t see myself obediently mouthing words I knew were lame. Let me at least give it a shot in my own words and see if maybe something jelled. I thought I was doing what Kesey wanted me to do.

Kesey has referred to what I wrote as “tying the story up in a Buddhistic bag.” Not true. There were a couple of lines from the Diamond Sutra, but that was just the amateur Orientalist Dr. Loach condemning himself with quotes from The Buddha. The con man also pulled some Nietzsche quotes out of his ass to punish himself with. Like I said, it was a self-laceration – and as far as what it was tied up in, it was much more of a biblical bag than Buddhist. Vanity of vanities, that kind of thing.

But, whatever. I’m not claiming that what I wrote was a great piece of literature, but it did raise the ante. The way Loach reproached himself in that soliloquy was a sudden, unexpected turn, and it raised the tension in the story. It was probably ridiculously out of place in our light-hearted romp. But all of a sudden, no one was getting a trophy for just being awesome. The spirit of Yahweh had entered Gerlinger Hall and he was not forgiving anybody for their sins. Dr. Charles Oswald Loach had just tried himself, found himself guilty, and condemned himself to hell.

After I finished reading, the room was quiet. I dropped the pages I’d pulled from my pocket into the manuscript box and went back to my seat trying to get an inkling of what the others thought of my piece. No one would look at me. Kesey got up and read the soaring epilogue he’d written. The audience clapped and cheered and it was over. Gerlinger Hall dissolved into a whirl of happy after-theater chatter, laughing, back-slapping, hugs and congratulations. I kept looking around for some form of affirmation that I’d done okay. No one would speak to me, except for Hal “Highwater” Powers, who came up and said, “Where did that come from? That was great!” He’d missed the last class and had no idea what was going on. I still have a soft spot for Hal to this day, because on that night, when I was to learn what it is to be despised, he was kind to me.

So, you read something no one had ever seen? Was this meant as an act of defiance? Was it perceived that way?

I was a naive kid. I believed in the book. I believed in Kesey. I believed it mattered that we were about to publish a book that wasn’t good. I made a mistake. It was a dumb kid mistake. I thought I was being the hero Kesey wanted me to be.

As far as I was concerned, reading my own piece wasn’t an act of defiance. It was an act of faith. I should have confided in Kesey beforehand that I was worried about the lack of an ending. I could have told him what I was going to do. But, for some reason, I couldn’t approach him. I was scared of what he might say. In the moment, when I reached into my pocket and read my own words instead of Kesey’s, it was as if I was Billy Bibbit, screwing up the courage to be the person McMurphy wanted him to be.

Yes, I’d broken the rule about not working on the book alone. But, I told myself a Ken Kesey book is not about following rules. It is about telling the truth.

And that’s what I thought I was doing. It was stupid. It was arrogant. It was wrong. But that’s what I thought I was doing.

I thought that Kesey and the others, even if they didn’t like what I’d written, would at least understand the spirit I’d written it in.

That was the stupidest thing of all. Of course it was perceived as an act of defiance. Any time you’ve got a Jesus figure, you’re gonna develop a Judas. That’s simply the molecule that forms in the presence of certain archetypes, sure as oxygen atoms are gonna find hydrogen atoms to bond with to make water.

Years later, there’s general agreement that the book is a failure. It kind of makes me laugh to read how blithely my fellow authors now dismiss Caverns as a bad book, as if they knew all along, and were just along for the ride.

Because, at the time, we were in a Kesey-enforced bubble of positivity. The book was gonna be a best-seller! It was gonna be made into a movie! Why, it might even win another Oscar! With Kesey, you were always either on the bus or off the bus. And there was no surer way to find yourself off the bus than to raise doubts about whether the book was good or not. Ironically, I was always one of the biggest supporters of the book. I was a believer. So no one was more surprised than I was when all of a sudden I found myself sucked into the vortex of Kesey’s shadow.

How did being “off the bus” manifest itself? What happened after the reading?

I’m a performer (a singer/songwriter) so I’m well acquainted with the euphoria that comes after a theatrical performance. Whether the show is good or bad, you just feel alive and full of energy.

The night after the Caverns reading was no exception. But it didn’t take long for me to realize the machinery of my universe was out of whack. Though friends in the audience slapped me on the back with approving words and smiles, none of my co-writers would look at me (except for Hal). Everybody was gathering at Kesey’s house on 15th street for the cast party. I figured I’d go. I didn’t feel bad about what I had done. I had my own euphoria going about having been brave enough to follow my literary instincts. Somebody had to speak up! Maybe we could discuss the whole thing and come up with a better ending.

Kesey’s parties were like something out of Gatsby. He had an instinct for it. Whether on the farm in Pleasant Hill, or in town, Kesey’s parties were the place to be. When my girlfriend, Marianne, and I arrived at the party, the house was lit up in the June night, the front door was flung open and people were milling all around, drinking and laughing. We made our way through the crowd and went inside. Kesey was holding court at the kitchen table still wearing his ringmaster’s attire, collar pulled open, a drink in his hand and a big, sweaty smile on his face. Proud papa bear with his cubs, in that beautiful warm kitchen light.

I wanted to join them, but they were in full tilt mode, so I just hung around the periphery browsing the buffet table. When I couldn’t take it anymore, I moseyed into the scene in the kitchen and finally took my chance. “So? What did you think of my piece?” I said.

The laughter stopped. “No,” Kesey said. “Un-uh. The guy fucks up the whole reading, and now he wants to talk about it? No. We’re not gonna talk about it. We’re never gonna talk about it.”

After this, it’s all so much like a movie, there’s no use even writing it down. People snickered, they laughed, they looked away, I tried to make a joke, I turned to run, stumbled into the French onion dip, spilled it all over myself and limped out of the room. I wandered around the party for a while still not comprehending the exile I’d entered. Finally, Marianne came up to me with a concerned look on her face. “We’ve gotta get out of here,” she said. “These people hate you.”

So, blah, blah, blah, she took me home, I kept wanting to talk, she kept hushing me. It’s all turned into one of those Southern Gothic movies in my mind, with Orson Wells playing Big Daddy Kesey and I’m Tony Franciosa, the wastrel son begging for his father’s approval. For me, it was Shakespearian, Greek, Gothic, Epic, whatever word you want to choose. Tragic. I loved the guy, wanted to please him, and now I was just a non-person. Nothing. Off the bus.

Part of me was amazed that I could have pissed him off that much. It was just a couple of paragraphs, after all. Five minutes at the end of a performance. It wasn’t as if I’d stolen the galleys and slipped a different ending into the printed manuscript. The book was still gonna be whatever he and the group wanted it to be. I clung to the idea that Kesey would ultimately understand my motivations, mete out some suitable punishment, and find a way to integrate me back into the group. One thing I knew about him was that he was a kind man, and that his impulse towards generosity of spirit usually won out.

But any inkling that this thing was going to blow over disappeared three days later, when I showed up at Kesey’s house for the next class. Kesey wasn’t there. Instead, he left a Whiteboard propped up in the middle of the room with a message scrawled on it that said The Rogue Reader had pissed him off so deeply he had to go off into the woods and be alone for a few days.

That’s when I knew this thing wasn’t going to go away. Now it had a name.

After this, did you ever talk to Kesey again? The other students? How did you get through the rest of the academic year and the book launch and appearances?

Yes, I saw Kesey quite frequently. And I saw the other students throughout the rest of that summer as we did final edits on the galleys. I was marginalized. No one ever said anything, but I think it was one of those situations where everybody expects the schmuck to eventually get the message and stop showing up. But, I wasn’t about to stop showing up. I felt I was as connected to the book as anyone else.

About a year later, the book was published. It was fun. There was a review in the New York Times Book Review. There was probably more attention paid to where Kesey was at as a cultural figure, than there was to the merits of the book. I think most of the literati thought of Caverns as another one of Kesey’s merry pranks.

I raised my daughter in Eugene, so I was part of that community, and I’d see Kesey from time to time. I always showed up for his events. He’d tell me he’d heard me on the radio. I longed to heal the rift between us, but you know, there’s that guy thing that makes it hard to talk about anything. I wrote him a letter apologizing, trying to explain my motives for what I did. I never heard back. In the end, I thought we had both just let it go.

It wasn’t until he died in November of 2001 that I found out it wasn’t that simple.

After Kesey’s funeral, I heard that Kesey’s official biographer, Robert Faggen, was looking for me. He wanted to meet The Rogue Reader.

So we met. Faggen had been the interviewer for Kesey’s Paris Review interview. I had never heard of The Paris Review, but Faggen informed me that a Paris Review interview is a big deal. It’s where the pantheon of great writers publish their definitive interviews, the ones in which their legacies are established. Hemingway, Kerouac, Miller, Gertrude Stein, Flannery O’Connor, they’re all in there. Kesey had wrapped up his interview with the story of one of his students from Caverns, who’d been a disciple of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and had tried to sneak Buddhist dogma into the book. Kesey and the class had punished the writer by sending him into exile. Then he proceeded to use the story as a cautionary tale about what a writer should not be.

Then he finished off the interview with a version of the speech he’d given the class before the reading, the one that had inspired me to re-write the ending. It was epic stuff. It had been epic stuff when it inspired a class of young writers in 1988. It was epic stuff to finish off a Paris Review interview with in 1995.

And it was epic stuff to leave as a permanent legacy:

“The writer’s job is to kiss no ass, no matter how big and white and appealing. The writer’s job is to say fuck you to God.”

I have no beef with Kesey’s message. I have no beef with Kesey as a mythologizer. Kesey was a myth-maker. That’s what he did, he was great at it and his greatest achievement was his own myth. But I was no shill. What I did, I did out of conviction. I was not writing some guru’s advertising for him.

The idea that I was a Rajneeshee secret agent was so bizarre I had to laugh. It was like being accused of being a member of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. I pictured myself talking into my shoe, getting orders from Mr. Big at KAOS headquarters: “Must…Insert…Sutra…Into…Book…”

Kesey claimed in the interview that he gave the fuck-you-to-God speech after the reading in Gerlinger Hall, as a lesson for his young writers. He said the class had wanted to string me up – and that the speech was Kesey’s way of making peace.

Well, there’s myth.

And then there’s bullshit.

It fit his story to make himself the peace-maker, and, after all, I was just an unknown kid. Who was gonna know that Kesey never actually made peace at all? That the naïve young college student was simply left to twist in the wind of the “literary Coventry” the class had exiled him to?

For an All-American literary hero like Kesey to leave a legacy of saying fuck you to God was big stuff. You don’t go on Charlie Rose and discuss the issues of the day with that kind of banter. Kesey was consciously choosing to go out as a revolutionary. That lifted middle finger at the end of the Paris Review interview was the cherry on top of the Kesey Myth.

So what if a few facts had to be twisted around to make the story play? That’s how magic works, you divert the audience’s attention, a little sleight-of-hand here, a little razzle-dazzle there, next thing you know you’re pulling a quarter out of some rube’s ear.

Faggen said Kesey had adapted the story of the Rogue Reader as a permanent feature of the lectures he was giving at college campuses around the country. He asked me, How does it feel to be infamous?

It feels all right, actually. I know the truth. I don’t mind being the rube in Kesey’s magic act. Kesey saw a way to turn real life into a parable. And guess what? The Rogue Reader is a pretty good parable.

But not as good as mine. Mine’s called The Boy Who Said Fuck You to God.

And mine’s true.

Why are you telling this story? Why not tell me to go to hell? How do you expect the rest of O.U. Levon will respond once this is posted?

As far as why I told you my story, because you asked. I originally wrote up my experience to explain the Rogue Reading to Faggen. Because he asked. As I told you right from the beginning, I will never participate in a Kesey hit piece. But I think an honest portrait of him could be quite interesting. I truly did love the guy, but he could be a bully sometimes. Once, he told me he thought the solution to the problems in the Middle East was to put LSD in the water supply.

He also said the most true thing I’ve ever heard anybody say about the state of the world. He said we’re all volunteers. Meaning, we can just get up and walk out of the nut house any time we want to.

Why didn’t I tell you to go to hell? I don’t know. You sounded sincere. You were interested. So I thought I’d share a story I thought was truly interesting.

And how do I expect the rest of O.U. Levon to react to my interview?

I expect them to think I’m a pain in the ass for not going along with their code of silence, for not just taking my punishment and shutting up. I doubt whether they’ve given me much of a thought over the last 25 years. To them, I’m sure, my story is just an unpleasant eddy in an otherwise groovy trip down memory lane. And I think they’d prefer to stick to Kesey’s decree not to talk about it. Ever.

Actually, there’s one other way the rest of O.U. Levon might react.

My story may open a floodgate of other stories that don’t necessarily burnish the Kesey Myth.

That would make me sad.

Even I prefer to remember the Nordic god who smelled of fresh straw.

Far and away the most interesting entry in this series.

Thanks, Ben, both for the great story and for your actions at the time. It sounds like yo really did piss him off by doing precisely what he had suggested: saying fuck yo to “God” and refusing to kiss any ass.

I never had the chance to meet Kesey. I think I’ve heard him speak once, at the Oregon Country Fair while Garcia was ion a coma. From everything I have read by him or abot him, though, I can see how he cold be both an asshole and a bully when his ego got piqued. Frankly, I’m glad he turned some of that energy on a very articulate writer who can take it and trn it into a good story of its own.

Rock on, Ben!

Thanks for a great story, Ben! People flew off of Kesey’s orbit like sparks from a grindstone. I knew a few of them when I played with the Anonymous Artists of America back in the 70s, the band which had played for the Acid Test Graduation some years before. Rules were made to be broken in style. You’ve got it, bubba!

Fascinating tale of truth, Ben. Good on you, brother.

Ben died today in Eugene. A dear friend to many, he is mourned and missed.