Twenty six years ago, Ken Kesey gathered thirteen students, most officially enrolled in the University of Oregon writing program, others not, to write a collaborative novel in one academic year. Classes took place at his home, but there were field trips too. Once, they toured around Eugene on a bus with no windows. Sometimes they went hiking into the hills. One trip led them to a strip club. Kesey screened old movies of The Merry Pranksters’ magic bus journey. There were parties with drugs and booze attended by famous hippies. There were fiery pep talks about the duty of artists. For nine months, the students wrote, fought, and at times fell in love. At the end of the year, Kesey gathered his flock on stage in thematic 1930’s garb for a culminating reading from their novel Caverns. He offered sips from his flask to his students before they took the stage. After the reading, People magazine and Rolling Stone came by. The group posed for pictures, famous several months ahead of the book’s release.

These events make up my favorite Ken Kesey story, one which often loses out to stories of his psychedelic bus tour or his acid tests with the Grateful Dead. Why would an established writer like Kesey put his name on the line for a bunch of students? Was it a reckless act of hubris, or a washed-up writer’s desperate plea for the spotlight? Little has been written about Caverns. Most articles published upon its release rehash Kesey’s old exploits while throwing in tidbits about the structure of the class. The process and product of Kesey’s class are unprecedented and under appreciated, in my opinion.

Last year, after reading a used copy of Caverns, I began emailing the book’s twelve living authors. Surprisingly, eleven responded. I’ve created an online space for their first person accounts of this book. In it, there are contradictions and disagreements. To me, that’s the best, most accurate form of history. Caverns belongs, ultimately, to the people who created it, blemishes and all. However, at the completion of this project, a few powerful themes emerged for me. Here they are:

Be Generous

For nearly a year, Kesey’s students were his primary focus. He hosted them in his home. His wife Faye served them food. They attended his parties. He hiked with him to his son’s hilltop gravesite. He wrote a book with them. This devotion and generosity is one of the most lasting lessons Kesey taught the Caverns crew.

In his introduction to Caverns, Kesey remembers a statement from Malcom Cowley, his former instructor at Stanford University: “Be gentle with each other’s efforts. Be kind and considerate with your criticism. It’s just as hard to write a bad book as it is to write a good book.”

In their recollections, Kesey’s students wrote of his kindness. While some have suggested that Kesey used his teaching position to eke out a book he couldn’t write on his own, nothing I encountered supports that theory.

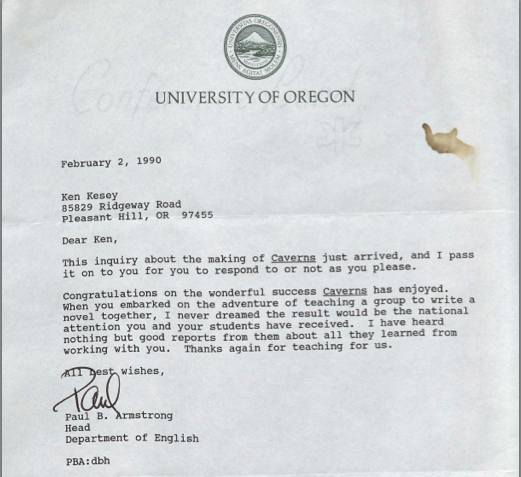

Dr. Paul Armstrong, the former head of the English Department at The University of Oregon, sought out Kesey in an effort to invigorate the writing program. When the two met for lunch, Armstrong sensed that Kesey, mourning the death of his son, Jed, saw teaching as a way to connect with young people again. Also, Kesey held great reverence for his time at Stanford where he learned a tremendous amount both from his instructors and his peers.

Kesey wanted to be a teacher, and he wanted to be a great one. He wanted to pass on all that he’d learned from his instructors and other writers. He may have even wanted to destroy the typical M.F.A. workshop teaching model by doing something fiercely cooperative. Caverns co-author Jeff Forester wrote, “Kesey wanted to pay it forward and believed that the best way to learn was by doing.”

Creativity Needs Community

Kesey wrote, “There is a binding tie about being part of a good, tight team, a bond that never fully unravels when the season ends and the members go their different directions.”

Kesey wrote fondly about his program at Stanford, particularly about the influences Malcolm Cowley and Frank O’Connor had on him. However, as important were Kesey’s classmates, (Larry McMurtry, Ken Babbs, Ernest Gaines, and Peter S. Beagle) an all-star crew with whom Kesey formed lasting friendships and used as early readers of developing work.

Kesey also drew on influences outside of the writing world. He loved people and often welcomed friends and visitors to his house on Perry Lane near the Stanford campus. His residence in La Honda became legendary as the launching point for the Furthur bus tour and the site of the first acid tests. Jerry Garcia played at those parties. Neal Cassady, a muse of the beat generation, was there. Kesey’s biography could be written through the examination of the different communities he helped create and the friendships he formed, from the University of Oregon wrestling team, to the Merry Pranksters, to the Caverns crew.

From the beginning, Kesey wanted to create a truly cooperative environment for his students. He’d seen the ego and competition that existed within traditional MFA programs and saw it as an obstacle to true learning. That was the inspiration for the group novel. “Even better than walk a mile in the other writer’s moccasins, mix them up until nobody can be sure whose are whose.”

When Kesey first met with Armstrong to lay out his vision for the class, he asked if he could network computers together so that the students could all work on the same document. What Kesey wanted was a Google document-like software which would allow everyone to type on the same page at the same time. His idea was several decades ahead of its time, and he was forced to make do with the technology that existed. Still, he insisted that the creation of new content for the book take place among the group in his home during class sessions.

“The energy with thirteen students who were all mature and capable. It was exciting. We would go to class and someone would strike a chord. Like Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, and Willie Nelson all getting together,” said Kesey.

Caverns as a novel is fine. The magic was in making a hodgepodge group of students into The Highwaymen. And, if as some have suggested, this class was meant as a way to heal Kesey’s heart after the death of his son, it was the community of these students that Kesey drew upon for that strength.

There is Art in the Process

Like any good protagonist, Ken Kesey’s biography is full of contradictions. Before becoming a child of the sixties, Kesey had been a disciplined, Olympic-level wrestler. Kesey spoke skeptically about other writers and academics, yet credited the Stanford University writing program with teaching him how to write. Kesey married his high school sweetheart Faye and stayed married until the day he died. Though devoted to one another, they both had sex with plenty of others while married. Kesey was a novelist who questioned the power of the novel as a medium.

His art spilled out of his books and into his public persona. Like Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, or Salvadore Dali, his work, public image, and private life all swirled together in a complex amalgamation that created a complex, ever-changing legacy. Nothing epitomizes this more than his famous bus trip with the Merry Pranksters, the subject of Thomas Wolfe’s Electric Kool Aid Acid Test.

This journey helped jump-started “the sixties” and for all of its disorder, drugs, and free love, Kesey had a vision of breaking down social norms while recording everything on film. The result was an American myth that’s being retold and imitated fifty years later.

To me, Caverns, like the bus trip, was more about the experience than the destination. “It was truly a lovely chaos,” author Ken Zimmerman said of writing Caverns. “Kesey played the role of bandleader, team coach, and occasionally the little engine that could, pulling us up over the steep hills whenever we got stuck.”

The art isn’t in the book itself, just as the magic of the bus trip isn’t in the video footage. The art lies in the process. This book is unique in literary history, not because of its great merit, but because it happened. Kesey envisioned the class, designed it, and shaped his crew into a team with a common goal.

A Final Thank You

Ken Kesey said of Tom Wolfe, “When he was around us, he took no notes. I suppose he prides himself on his good memory. His memory may be good, but it’s his memory and not mine.” From the beginning, I took the vantage point that whatever stories came to me about Kesey and Caverns were valid because they existed for their storytellers. The interviews I’ve posted create a fragmented collage of how Caverns came to be.

My own reflections here are biased and gleaned from second hand accounts. Still, I’m entitled to them, and spending a year corresponding with Kesey students has changed my perspective on my own work and life choices.

I’m more aware of the importance of the people who influence my thinking, both other writers, but also other thinkers, the people who challenge my ideas or provide new perspectives. I more easily notice generosity, both from those that help me and those whom I help. Most importantly, I’m learning to see everything I do as a contribution to a larger canvas, contributions to my art rather than impediments to it.

DC writer/editor Richard Peabody once said, “The problem with being a writer is that when you’re writing, you feel guilty about ignoring friends and family. When you’re with friends and family, you feel guilty about not writing.” I find this to be fairly accurate. What was beautiful about Kesey, is that he did not see this dichotomy so distinctly. He let so many people, events, and adventures into his art. In the end, it’s not just his books that remain, but also all of the communities he helped shape and the myths he created.

I’m deeply appreciative to all of the Caverns authors who took the time and effort to contribute to this project, to Dr. Paul Armstrong, Dr. Timothy Tays, and Linda Long and the University of Oregon Library. I’m pleased that the story of Caverns exists in this way on the web, and grateful for what I’ve learned in putting it up here. Thank you all.

Thank you so much for undertaking this project. It’s wonderful! I think Ken Kesey would be proud of you. I am grateful to you.

Thanks, Tim. I’m grateful for people like you who share their time and energy with me.

Wonderful entry. Possibly the best I’ve come across.

Thanks much, Sherice.