In 2025, I read 65 books. This includes fiction and nonfiction in both print and audio form. For the past several years, I’ve created a rundown of my favorite fiction and nonfiction books. This year, I’m only making a fiction list, because I am not significantly excited about 5 nonfiction reads. You can see my past book rundowns below.

2024 fiction 2024 nonfiction 2023 fiction 2023 nonfiction 2022 fiction 2022 nonfiction

This list excludes classics and books by people I know. I don’t think you need me telling you I still like Shirley Jackson or that you should buy my friend’s book (though I will promote friends elsewhere).

Here’s my list in no particular order.

# 5 – Sky Daddy – Kate Folk

Kate Folk’s debut collection of short stories, Out There, showed an oddball sense of humor, a searing insight into modern social structure, and an underlying feeling of melancholy. I picked up her novel, Sky Daddy, quickly after it came out.

It follows Linda, a young woman with a sexual fixation on airplanes, whose ultimate desire is to “marry” an airplane by dying in a deadly crash. While the premise’s absurdity certainly appealed to me, Folk handled her character’s unusual longing with care and sensitivity. Linda’s relationships with humans were full of second-guessing, ruminations, and uncertainty about how hard she should try to fit in.

# 4 – Annie Bot – Sierra Greer

Doug’s robot, Annie, fulfills his every sexual desire. However, serving him becomes more difficult than she expects, as it’s not always clear to her how to be the optimal companion. Her own growing self-determination becomes a problem too, and the book wrestles with familiar themes found in Blade Runner, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, and I, Robot.

What sets this book apart is the way it addresses sexuality and gender. Buy it for the robot sex, but enjoy it for the complex untangling of romance and patriarchy.

# 3 – Stag Dance – Torrey Peters

Transgender author Torrey Peters’s 2021 novel Detransition, Baby followed a young trans woman navigating gender identity and messy relationships in New York City. Stag Dance, a book of several stories (and maybe a novella?), felt like a vastly different book to me.

The title story is set within a community of lumberjacks in Montana in the early 1900s. My favorite story in the book, The Chaser, takes place at a Quaker boarding school. In every story, there’s a permeating feeling that no one’s gender identity or sexuality should be assumed or will remain fixed. As a reader, this felt like an author treating characters with great sensitivity and care rather than any kind of statement about societal norms. In that way, it felt like Peters opened up a whole new way of examining characters and exploring possibilities.

#2 – I Who Have Never Known Men – Jacqueline Harpman

Forty women are imprisoned in an underground bunker with no memory of how they got there and no idea as to what is happening in the outside world. The main character, a girl and the youngest of the 40 women, is the only one who does not have a memory of a time before living underground. She must construct all of her knowledge from the stories and advice offered by the women around her. Some of the women are growing old, and as the youngest of the group, the girl becomes the group’s best hope of escape.

Originally written in French and out of print from 1997-2022, this book is a sci-fi masterpiece. I think it’s a tremendous example of starting a story in the middle and moving forward without slowing down for backstory and exposition.

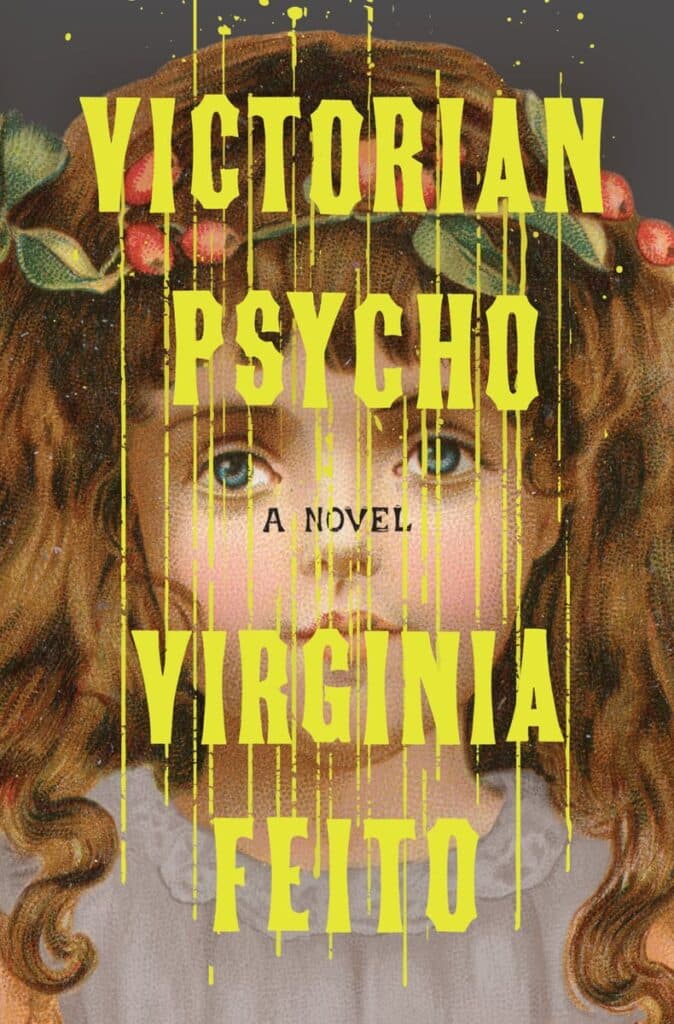

#1 – Victorian Psycho – Virginia Feito

Sometimes my favorite books are the ones I know I should not recommend to other people, and this is one of those books. It is violent and gruesome in the most unforgiving and over-the-top way. It’s so gruesome, it becomes comical. The best comparison I can make is to the Oliver Stone movie Natural Born Killers. Bloodshed becomes almost slapstick in the most uncomfortable way.

Winifred is a young governess who must cater to all of the peculiarities of her employer’s family, and in that way, it contains all the tropes of a buttoned-up Victorian novel. What makes this novel unique is the slowly building violence with which Winifred responds to the difficulty of her living situation.

I read Virginia Feito’s well-received debut, Mrs. March, and did not like it at all. It was safe and, to me, not so interesting. This is the novel I wanted, the kind of thing that might not get published if you don’t put out a successful mainstream book first.