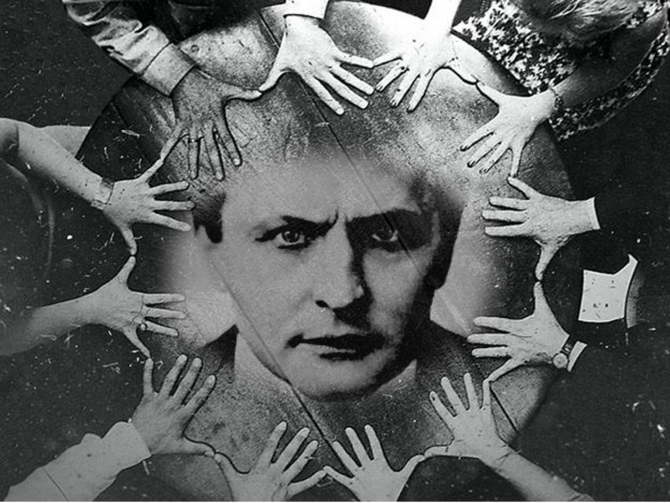

Halloween marks the anniversary of the death of Harry Houdini. Each year, spiritualists attempt to make contact with the dead escape artist, an annual tradition I’ve written about in both fiction and nonfiction forms.

May story “The Great Escape” first appeared in Second Hand Stories and later in my books Frida Sex Dreams and Other Unnerving Disruptions.

The nonfiction piece, originally published in Dirge in 2016, is below.

Escape from Afterlife: A History of the Harry Houdini Halloween Séance

This Halloween, magicians, spiritualists, and fans will attempt to contact Harry Houdini from beyond the grave, a ninety-year-old tradition born out of a widow’s promise to her dead husband at a time when spiritualism enjoyed rampant popularity and even scientific support.

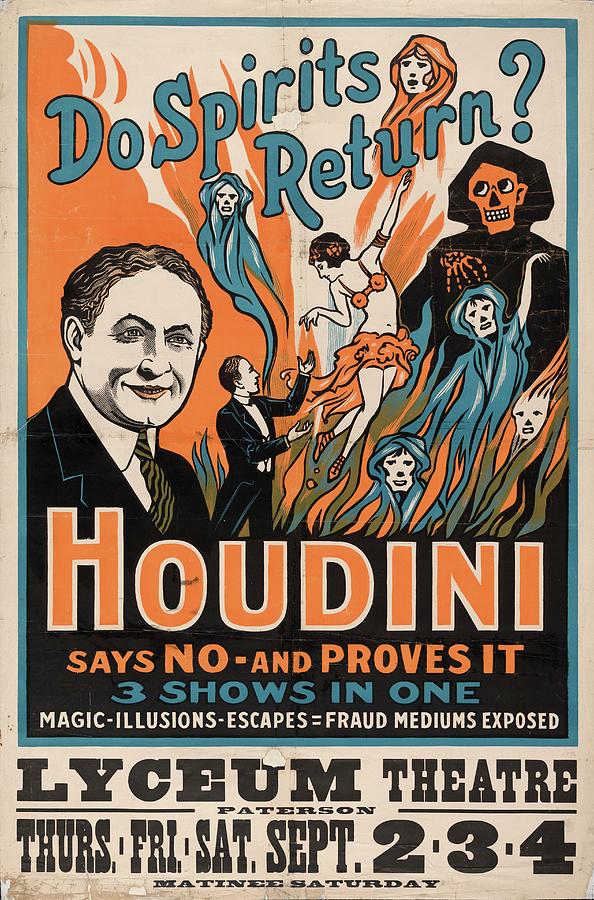

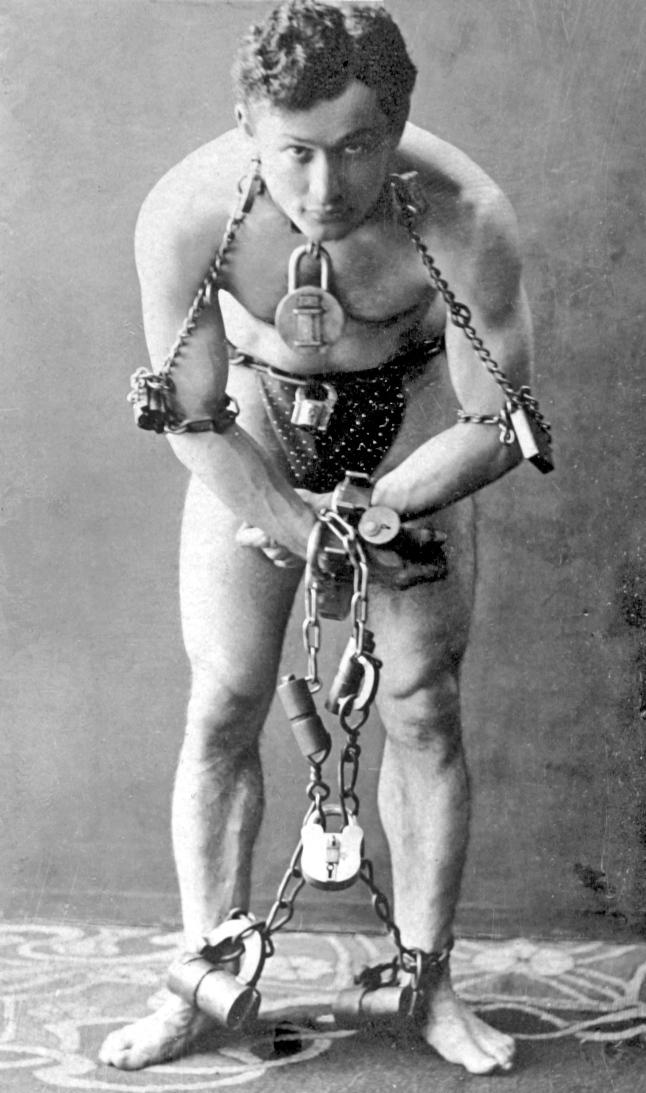

Houdini, aside from being the most famous magician and escape artist in United States history, also crusaded against false mystics and seers who fleeced mourners desperate to contact dead loved ones. However, Houdini’s skepticism also carried with it a deep desire that one day someone would prove him wrong.

The son of a rabbi, Houdini grew up with deep-seated ideas about the separation of the soul from the physical body. When his father died, 18-year-old Houdini sold his watch to pay a medium to make contact. Houdini recognized the encounter as a ruse when the medium declared Rabbi Weisz was “very happy,” a statement that didn’t match up with the many debts he knew his father had left his family.

Quick to learn and eager to earn money for his family, within five years of his father’s death Houdini himself became a “mystical entertainer” fabricating encounters with the dead for paying customers. “At the time I appreciated the fact that I surprised my clients, but while aware of the fact that I was deceiving them I did not see or understand the seriousness of trifling with such sacred sentimentality and the baneful result which inevitably followed. To me it was a lark,” .

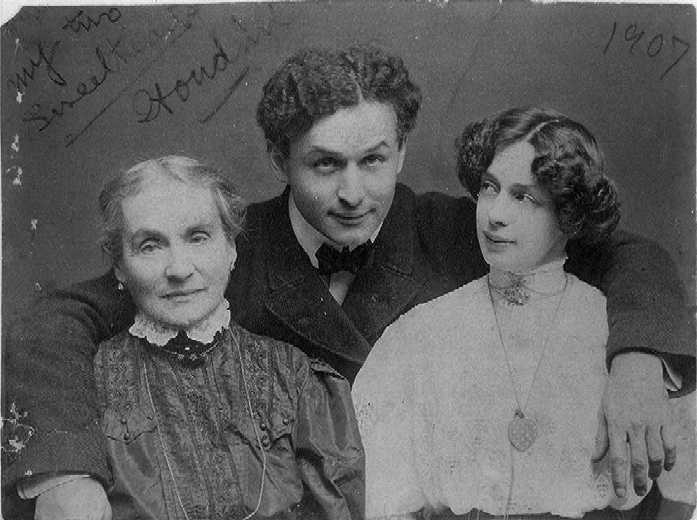

Being in on the deception did not stamp out Houdini’s hope that there remained genuine mediums who could communicate with the dead. When his mother died in 1913, Houdini tried to communicate with her as well. Houdini claims to have attended over a hundred séances during a 1919 trip through Europe, and to his own disappointment, found fault in all of them.

“Even after our numerous disappointments, whenever we visited a new medium, Houdini, with his eyes closed, would join the opening hymn, and then sit with a rapt, hungry look on his face that would make my heart ache,” said his wife Bess.

Over the course of his life, Houdini established code words with fourteen friends so that he would know if they tried to make contact with him from the afterlife. This too proved fruitless.

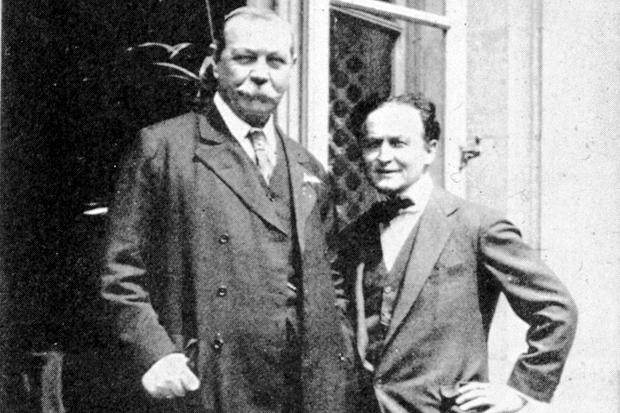

In 1924, Houdini published , a detailed debunking of spiritualism. He also offered a $10,000 reward to anyone who could prove genuine contact with the dead. Houdini’s zealous refutation of spiritualism caused a rift with his friend Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle was an ardent believer in spiritualism, who also believed Houdini possessed supernatural powers, whether the magician realized it or not.

Despite all of his doubts, Houdini held out hope that he himself, being the greatest escape artist of all time, might some day be able to escape the afterlife and make contact with the living.

Before his death, Houdini and Bess made an agreement that whoever died first would try to make contact with whomever remained alive using agreed upon code words. Efforts from both parties were to continue for ten years after death.

Houdini died in 1926. Bess continued to offer $10,000 to anyone who could prove genuine communication with the dead. This perpetuated the Houdini mystique as mediums and psychics continually made claims of contacting Houdini in the afterlife.

One of these mediums was Arthur Ford who, less than a year after Houdini’s death, claimed to be in touch with Houdini as well as his mother. Ford even produced the agreed upon code word, “forgive,” Houdini’s mother had promised to use when contacting her son from beyond.

Bess remained skeptical, telling The New York Times, “I want more details before I’m certain. I am sure I am the only person who knew the code word of Houdini and his mother. He and I arranged a more complicated code, containing ten words. If I got them, I would be certain.”

In 1929, amidst struggles with grief, and alcohol (and ), Bess, who’d recently suffered a fall and was heavily bandaged, watched from the couch as Ford conducted another séance, this time producing the agreed upon ten word code. Bess issued a statement acknowledging Ford’s legitimacy in which she said, “…I am absolutely convinced that my husband talked to me and that there is life beyond the grave.” Newspapers followed up with sensational headlines.

A short time later, New York Graphic published a story with the headline “Houdini Message a Big Hoax! ‘Séance’ Prearranged by ‘Medium’ and Widow.” The article claimed Bess and Ford met beforehand to create the spectacle, an attempt to rekindle interest in Bess and launch her return to the stage alongside Ford. Though it did not appear in print, rumors swirled about a personal relationship between Ford and Bess. She later withdrew her earlier statement and said that neither Ford nor anyone else had produced the code upon which she and her husband had agreed.

In 1936, Bess and Dr. Edward Saint (her business manager and partner) announced they would host one final séance on Halloween night on the rooftop of New York City’s Knickerbocker Hotel. 300 spectators sat in bleachers, were served by hot dog vendors, and watched as Bess Houdini, next to a framed picture of her dead husband, joined the famed spiritualist in trying to make contact. An estimated 6 million more listened in over the radio. Later, producers , added narration and editing, and sold it as a record.

Saint conducted the séance with much fanfare, begging Houdini to give a sign of his presence. After the theatrics, then silent meditation, Saint and the others gave up, and Bess declared, “My last hope is gone. I do not believe that Houdini can come back to me, or to anyone. After faithfully following through the ten-year Houdini compact, using every type of medium and seer, it is now my personal and positive belief that spirit communication in any form is impossible. I do not believe that ghosts or spirits exist. The shrine has burned for ten years. I now reverently turn out the light. It is finished.”

This did not end the Houdini séances, however. Many other magicians and spiritualists have taken up the cause with various claims of authenticity. Debates about the authenticity of spiritualism have given way to campaigns and in the modern age of showmanship and money making.

This year on Halloween, the 90th anniversary of Houdini’s death, magicians and mediums around the country will try again to contact the spirit of Harry Houdini, some for profit, some out of genuine hope. Despite his lifelong fight against spiritualism, Houdini’s name still conjures up mystery and a willful ignorance of fact and science as some hang on to the hope that the great escape artist will free himself from his unearthly confines.

Resources:

1. by Christopher Sandford

2. by Harry Houdini

3. The New York Times and The Washington Post Archives.