Listen to the podcast episode here. The transcript is below.

World War I combat veteran, 3-time winner of honors for life-saving bravery, daredevil, and riverman responsible for saving 27 lives and recovering 177 bodies from the water, Red Hill Sr. was a larger-than-life hero in Niagara Falls. Hundreds of thousands had lined the banks of the river to watch his daring rides through the rapids. The old scow still grounded near the brink of the falls served as a monument to Hill as much as any headstone, a reminder of his daring rescue of the men once stranded aboard. The same of the ice bridge that formed each winter which locals were no longer allowed to traverse after the day it broke apart and Red Hill Sr. pulled a teenage boy safely to shore.

His death at age 53 took an icon away from the community. His eight kids lost the father who had taught them everything about the river, the wildlife around it, and the daredevils who tried to tame it.

Welcome to the Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. In this podcast, we’ll examine the bravery, stupidity, hubris, and eccentricity of people who have attempted daring feats at Niagara Falls. My name is Theodore Carter. I’m an author whose novel research went too far, and I got swept up in the current of stranger-than-fiction stories surrounding Niagara Falls. Now, I’m putting that research into this podcast.

Several years after his father’s death, Red Jr., at age 32, was nursing a rocky marriage and working as a tour guide, game warden, and at the family souvenir shop. Longing for something greater, he put together a team for a run down the rapids which included his brothers Corky, Wesley, and Major. He chose his father’s barrel from 1930 for the trip, the one with lettering on the side listing all of his father’s heroic accomplishments. Junior wasn’t worried about living in his father’s shadow. He stepped into it.

On July 8, 1945, wary of watching police officers, Jr.’s team snuck the barrel out of the souvenir shop and down to the river. As it lay waiting, someone cut the ropes holding it on shore. It bashed against the rocks and picked up a few dents before his team recovered it. He could have regrouped for another day, but 200 thousand people lined the river and Hill did not want to disappoint them. He made the 7-mile trip through the lower rapids emerging from his vessel battered and bruised, but alive. He had laid the groundwork for the next generation of Hill daredevils.

Hill’s mother, who had tried to talk him out of the stunt, who had seen too much death on the river, suffered a mild heart attack that day. She’d disapproved of her husband’s daredevil antics, and wasn’t eager to watch her children risk their lives in the same way. Still, there wasn’t much she could do about it.

Corky Hill pulled off the next stunt when he swam across the lower river later that year, just as his dad had done. Corky had already made a couple animal rescues on the river, at one time lowering down 125 feet into the gorge by rope to save a cocker spaniel.

Now, Major and Red Jr. were each scheming about going over the falls. Major, like Red Jr. was struggling to scrape by in the aftermath of their father’s death and working through a rocky marriage. Both brothers ran into trouble with the law. Major stole mechanics’ coats and tried to sell them. Red Jr. was arrested for an illegal scheme selling hunting and fishing licenses. Major also carried physical and emotional scars from his service in World War 2.

Hard times continued when the family lost their souvenir store and all in it to a public auction. The Hill barrels no longer belonged to the Hills. Both Major and Red Jr. were drinking heavily.

Stunts on the river remained one way to reclaim glory. In 1948, Red Jr. shot the rapids again in front of a crowd of 100,000 with the help of Wes, Corky, and Major. Corky, who missed work for the event, lost his job.

The following year, Major was ready to run through the rapids again and add his name to the list of Hill daredevils, and had a new red white and blue barrel designed and built, his brothers there to assist. During the run, however, his barrel got caught in a vortex. Red Jr. helped pull the barrel to shore, and when Major crawled out, a sudden surge caught the barrel and pinned Major’s leg. A newspaper report described him as “splattered with blood and close to unconsciousness.” With no way to reach the injured Major, the fire department lowered a rope down 256 from the overhead aero car tram.

Here’s the event as reported with the full dramatics of a mid-century newsreel.

(Audio from newsreel)

Major spent the night in the hospital, but rumors swirled that his Red Jr. might finish the trip, repeating an indignity their father had given Bobby Leach decades earlier. This, to Major, was unacceptable, so bandaged leg and all, he left the hospital, got back into the barrel and finished the trip.

Now, with both Major and Red Jr making a run through the rapids and Corky swimming the river, there was one looming stunt left, one elephant-in-the-room feat that the Hill family had never accomplished, that their father talked about, dreamed about, but also thought too terrible to ever attempt: Going over the falls in a barrel.

“I told them it would be fatal. What was there left to prove?” Wes Hill had said. (Clarkson p. 184). The Hill family had gotten to know and dined with men who’d died making the attempt including Charles Stephens and George Stathakis. Also, the hill brothers had fished dead bodies out to the river for a fee for decades. If there was any clan who knew how deadly the falls could be, it was the Hills.

Major announced he would be the first Hill to go over. He commissioned the construction of a steel barrel, and put together a crew which noteably did not include Red Jr. Major and his brother’s relationship hadn’t recovered from Major’s rapid run.

Hundreds of thousands of spectators lined the river on July16, 1950 to watch the first attempt at the falls since George Stathakis’s fatal attempt twenty years earlier. Major’s crew dragged his barrel into the river and set it on its way but 200 yards from the precipice, the barrel ran into a reservoir of the hydro electric plant. Stuck, it spun and churned for over an hour. By the time Major’s team got the barrel free, both the barrel and Major were battered and tired. Major wanted to continue, but hydro workers and the police on hand, the opportunity had passed. Hill climbed out of the barrel. His team sent the barrel down without Hill in it eager to test its durability, much to the delight of the gathered crowd, many of whom didn’t know Hill was no longer in it.

Major told reporters he’d make another go within a week, but the barrel sustained enough damage that day to put off another attempt. Later that summer he made a run through the rapids which drew a smaller crowd than previous Hill attempts. The rapids were a poor substitute for the promised trip over the falls after all.

The barrel, which had taken so much time and money to build, came out of its two stunts perhaps more dented and bruised than its passenger. Major hill retired it to the family souvenier shop delaying another attempt at the falls.

Now, it was Red Jr. who talked of beating his brother down the falls in a Lussier-styled rubber ball. Something inside of Red Jr, maybe a love for his father, a rabid competitiveness with his brother, or desperation coming from the need for money and family troubles, pushed him. to move quickly. The perfect vessel for a run at the falls, takes time and money. The first of which Red Jr. was unwilling to spend, the latter of which he couldn’t.

The contraption Red Jr. had unveiled for this daring stunt looked as if it carried all of that struggle and sadness he did. Named “The Thing,” it consisted of thirteen inner tubes lashed together and covered with a fishnet. To many who saw it, it looked like certain death. Lussier, who’d been talking about making a second attempt for years, said, “I wouldn’t go down the Chippawa Creek in that thing.” (Clarkson 196)

Red Hill Sr. had told anyone who wanted to know that the best vessel design for a trip over the falls needed rubber to cushion collisions with rock and that it had to be light enough to avoid getting stuck behind the cascade. Jr.’s “The Thing” had these qualities, but in no way did it have the craftsmanship and technology of the Leach, Stathakis, Stephens, or even the Annie Edson Taylor barrel.

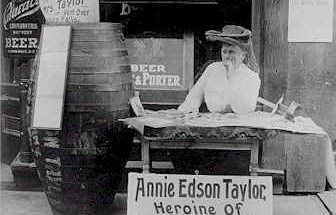

Local rivermen, family, and advisors stood by helpless as Red Jr. spit bravado at the local papers about his supreme confidence, while they knew that “The Thing” would be the end of him. Unlike the reporters, friends and family knew Red Jr. was at a low point. To him, his life felt as if it were slipping away from him, and this was his chance to grab it back. He had Annie Edson Taylor-like desperation, the kind that made death feel like an acceptable risk.

Hundreds of thousands had gathered around the falls to watch, and the event was covered by radio and television in a way his father never could have imagined. Major was a notable omission from the team that towed Red Jr. out to the river on August 5, 1951. His brother Corky was on hand along with other trusty riveremen. When the assembled crew let The Thing loose, it bobbed and weaved in the rapids, but was light enough to stay on course unlike Major’s barrel, and it made the plunge.

When his crew made it’s way out to The Thing below the falls, three of the inner tubes had popped off, and Red Jr. wasn’t inside. Someone spotted the interior padding floating in the river. Someone else saw Red’s shoes. Some onlookers think it was a hoax, that he was never in it, perhaps jaded by Major’s empty barrel run a year earlier.

There was no body to mourn over. Hill’s family, including his mother, siblings and cousin, cry knowing that there’s no way Jr. could have survived, knowing better than anyone that the falls sometimes keeps bodies for awhile, leaving them to be dragged out later, sometimes for a fee.

The next day, his body washed up in the exact spot the riverman knew to look for floaters.

Beatrice Hill, mourning the loss of her husband and her son, convinced twenty-eight-year-old Corky to quit the river and avoid the mania that’d overtaken Jr. and Major. He took on a job building a tunnel for the expansion of hydroelectric power. His second day on the job, he was crushed by a falling rock and died.

For Major, this was somehow justified in continuing with daredevilry since life away from the river could be deadly too. Death could come at any moment. In 1954, Major made another run at the rapids. When his barrel drifted to shore midway through, the police arrested him. He made another run in 1956. He talked of taking a specially designed rescue boat through the falls, but it never materialized.

Major, the most prominent Hill daredevil still alive, continued to hold court and made some money telling stories about his legendary family, consulting on a new TV documentary, and collecting his veteran’s pension. He lamented that helicopters had replaced riverman in recovering floaters, exhausting what had been a source of income for the Hills for decades. He talked of constructing a new rescue boat and was set to take it through the rapids, but the stunt never transpired.

Major drank too much. His right leg had been amputated below the knee. Beatrice told a reporter” People in town say he’s a drunk, a freeloader, but let me tell you, he’s not the same Major. The war and the river took care of that.”

1971, he was picked up for public intoxication and died in his cell.

Wes Hill stayed away from stunts, but stayed close to the river recovering over 100 bodies and saving fifty lives. Wes Hill consulted on films like Superman 2 and Blues Brothers 2000. He died in 2006 at the age of 76.

Descendants of the Red Hill are still in the Niagara Falls area today, though we were not able to connect for an interview for this podcast. In 2018, Kipp Finn, the great-grandson of Red Hill, ran for Mayor of Niagara Falls, Ontario. When talking about local residents, he was quoted as saying “they feel they’ve been forgotten.”

The Niagara Parks Commission held a ceremony to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the scow rescue. Kip Finn, and Red Hill’s grandson Dan Hill, as well as other descendants were on hand. The sound you hear in the background that threatens to drown out everything else, that’s the roar of the river.

(Audio from Award Ceremony)

Like the scow, the legacy of Red Hill remains, buts it’s shifting, moving. The Parkss Commission knows that some day, that scow will go over the Falls. If people are going to remember the story, we’ve got to leave some plaques behind.

(Audio from Award Ceremony)

Thank you for listening to The Niagara Falls Daredevil Museum. If you’re enjoying the show, please write a review and tell a friend. Also, please consider connecting on social media. On Twitter and Instagram, I’m theodorecarter2. I’m also on Facebook as well, and there, you can join the public group “Niagara Falls Daredevils” to share your own stories and engage in discussions with others. This show is just me. There’s no funding behind it or other people behind the scenes. So, I’d love to hear from you to know more about what you enjoy, what you think I got wrong, or which daredevil I should research next.

The music you’re hearing now is from Holizna, slightly altered in parts for use in this podcast.

The background music is “Photography” by Alex Productions. {Photography by Alex-Productions | https://onsound.eu/ Music promoted by https://www.free-stock-music.com Creative Commons / Attribution 3.0 Unported License (CC BY 3.0) }

Newsreel footage used was used under a creative commons license.